Tearooms are romantically portrayed as cozy and pleasant places to relax and enjoy teas with cakes, biscuits and sandwiches. Tearoom mythology is reinforced through evocations of scones and clotted cream. Hidden behind the Olde Worlde facade is a darker history. These unobtrusive locations became a force exploited by well-organized militants. They pushed aggressively to undermine the Constitution of the USA and the foundations of British and Canadian law.

There were three thrusts to this tearoom subversion:

- Use demographic and social shifts to create a new industry, in terms of both providers and customers. This bypassed established regulatory, banking and business procedures.

- Create an organizational base for mobilizing militants and coopting sympathizers. It provided a respectable cover for anti-establishment programs and recruitment.

- Destabilize family life and roles. One of its rallying cries was that our place is in the tearoom, not the home.

The single cause of all this can be summarized in one word: Women.

This opening is phrased flippantly but entirely serious and accurate. The tearoom was core to the Women’s Rights movements of the 1860s-1920s, in the U.S. and British Empire. It formed the base for a political revolution of extraordinary honor, tenacity, and character.

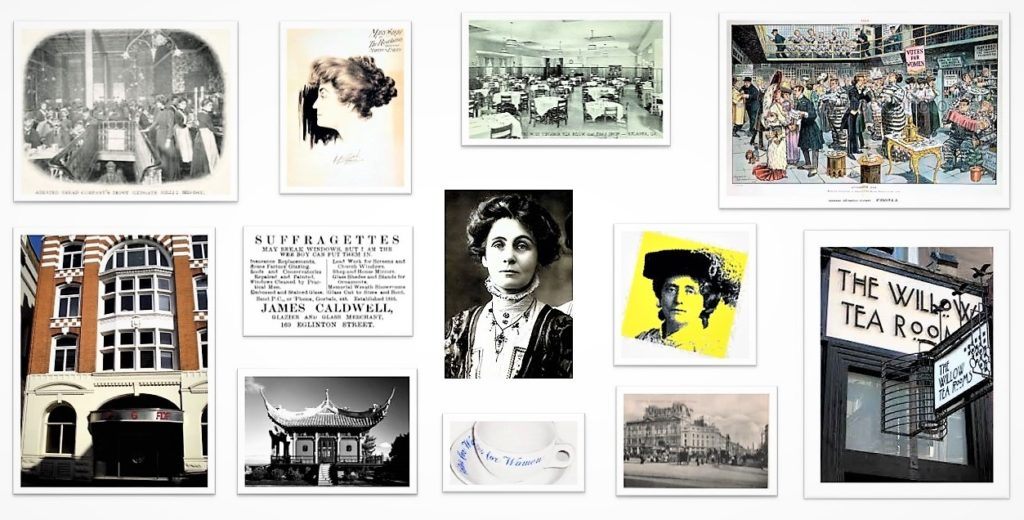

Just a few of the tearooms that created new spaces for women as customers. new political bases and the leaders who exploited the, and the entrepreneurs who created them.

Just a few of the tearooms that created new spaces for women as customers. new political bases and the leaders who exploited the, and the entrepreneurs who created them.

This paralleled and interacted with a business revolution. For the first time women stood out as the innovators and entrepreneurs. The tearoom freed women to build their own small businesses, a first. It provided a space for them to build an identity and action outside the home. Very much a first.

The tearoom business revolution

For the first two centuries of increasing, almost addictive, tea consumption in Europe, there were no tearooms. Tea was served in the home and women stayed there.

In the 1680s, the combination of coffee and sugar had created an entirely new type of establishment. This was the coffee “house.” That’s a far more expansive term than a tea “room.” The coffee house became a public center for business deals, the press, and political lobbying. It was also entirely masculine; women were legally barred.

Tea took over from coffee as the national drink of choice. But there was no tea equivalent of the coffee house. Tea stayed at home. Thomas Twining built his reputation through Tom’s coffee house. He also become the first elite merchant and skilled blender of tea. But, he never set up a tea house. Instead, he opened a store next door. His teas were in great demand from women whose households could afford the high cost of tea, 10-20 times today’s prices.

But they couldn’t enter to store to buy. Convention blocked them even getting out of their carriage to stroll to its door. They had to wait while the footman handled everything. It is hard to imagine the social isolation of most women. Even as late as the 1910s, many U.S. and UK reports show they could not even get served in restaurants without male accompaniment.

Tearooms were a major force in changing this.

The first tea room

It wasn’t until the 1860s that the first establishments serving just tea began operation. They were given the disarming name of “rooms.” Many were just that, a section of a house setup up with no need for financial capital. They were almost all owned, run and staffed by women, something unique. These commercial innovations reached critical mass in the 1880s in the U.S. and UK and peaked in the 1920s.

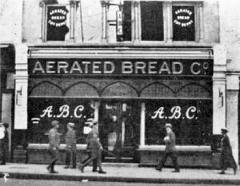

The first recorded tearoom was launched by The Aerated Bread Company, in 1862 in England. This was almost exactly 200 years after the Portuguese princess, Catherine de Braganza, introduced tea to England. (Yeah, sure. Sort off. Not really.)

ABC’s innovation took off among the new class of female workers benefiting from the jobs and wages of the Industrial Age. By 1923, ABC operated in 250 locations. It remained in business until the 1980s, when it was acquired in a merger.

These and the flood of new tea havens attracted women rather than men. They already had plenty of choices of where to dine and relax. The tearoom was one of the single most effective vehicles for expanding females’ space of autonomy, safety, and respectability. It was a public place that welcomed women. It was also inexpensive, unlike a restaurant.

Women were gradually entering the new labor markets. The typewriter created a need for a large new pool of educated workers, at low cost. Women were waiting for the chance. By the 1920s, it was taken for granted that office work was women’s work. Growing economic growth stimulated what we now call the service economy. Shopgirls staffed the new department stores. An increasing fraction of the population moved out of the endemic poverty that the Industrial Revolution initially brought.

They were ideal customers for this new style of business. ABC became a favorite for the unaccompanied women it targeted. They could even bring a male friend as their guest. It was the first multi-location business to offer toilet facilities for women.

Naturally, tearooms soon became discreet, private centers for friends to meet and talk. As women’s rights groups began to organize and mobilize, where better to gather? In London, Newcastle, Manchester, New York, Chicago, and Sydney the tearoom-women’s rights links tightened naturally with the growth of this entirely new institution. One blogger usefully headlined this as “from sheltered autonomy to sites of protest.”

The new tea room entrepreneurs

Tea room services require tea room owners. Business had essentially been closed to women, as were professional jobs. They could not become doctors or lawyers or get college degrees. The strange legal doctrine of “coverture” mean that women were the literal property of their husbands: Here’s the standard statement, from the main manual of British law, that was the base for U.S. continuance:

“By marriage, the husband and wife are one person in law: that is, the very being or legal existence of the woman is suspended during the marriage…”

Ironically, coverture was the only way a woman could be involved in business: as a co-property part of her husband’s. The long-term success of Thomas Twining’s firm was greatly enabled by Mary Twining, his son’s widow, who ran the company for almost 20 years.

But she would not have been able to start up and head a new enterprise. Women were banned from running “restaurants.” They could not apply for business loans, be involved with alcohol sales or intrude on the coffee house culture.

But as mobility and economic growth increased, they could open up a little space in their house or in a rented location. Tea was a natural, familiar and socially acceptable commercial opportunity – just a room. It was a cash business and needed little capital or inventory. One of the attractions for customers was a cost and recruitment advantage for owners: waitresses, not waiters.

The automobile day trip: let’s stop at a tearoom

More and more forces expanded the cracks in the walls that had blocked women in business for so long. The car was one. By 1920, there were eight million in the U.S. They were mainly used for leisure trips, not for work or commuting. Families on a day out wanted to be able to stop for light refreshments, encouraging the expansion of small women-run businesses in rural tourist areas.

In the U.S., the Temperance movement boosted tearooms at the expense of bars. The boom in home economics training, the only available career development education for professional women, expanded the range of foods and times of serving: adding breakfast and lunch to afternoon tea. (One review of the tearoom boom breathlessly describes the 1920’s as the decade of the salad.)

Two superpreneurs

Two figures stand out in the business side of the tearoom revolution: the Scot Catherine Cranston and the American Frances Virginia. Cranston focused on bringing ambience, elegance and a welcoming atmosphere for ordinary folk to get a inexpensive tea and meal. Virginia put her energy into the food but was equally centered on a place where customers were well-treated and well-fed, with food that was nutritious as well as delicious.

Cranston’s peak achievements were in the 1880s through to 1917, when she sold off her businesses after the death of her cherished husband. Virginia build her famed tea room in Atlanta at the end of the 1920s and ran it until the 1950s when she retired through ill health.

Catherine Cranston, 1880-1930 Starbucks with fine arts

Catherine “Kate” Cranston was elegance personified, had stunning taste and was a creative and generous mentor of outstanding architects and designers in the Art Nouveau tradition of the early 1900s. Her Willow Tea Room remains iconic – could you imagine a Starbucks coffee house or McDonald’s being carefully reconstructed as a working museum as this has been?

She was the daughter of a self-made hotel owner and her brother was a tea trader. Glasgow, the largest city in Scotland had seen many tearooms pop up, but they were largely served basic tea very much in the fast food style. They were also more pricy than most Glaswegians could afford.

Cranston saw an opportunity to create an “art tearoom.” She was a strong supporter of the Temperance movement and wanted to attract customers from all classes with an ambience that made this an attractive place to relax and to be at ease.

The Room de Luxe of her last and most famous tearoom, The Willow Room, is a triumph of fusion of form and function. Cranston defined the function and had an eye for the best talent to provide the form. She commissioned the well-known architect and designer, Charles Rennie McKintosh and his artist wife, Margaret McDonald. They played an increasing role in her new ventures over a 20 year period. It’s their work that makes the Willow Room so worth preserving.

Cranston’s left less tangible traces. It was in many ways the invention of concepts taken as given in business today but for which there seems no earlier major instance, whether led by a female or male. In the abstract, these are customer care, customer relationship management, customer intimacy, and the like.

The draw of tearooms in general was to turn women into customers. Cranston made anyone into a customer. The elegance of the Willow came with low prices. A foreign reviewer summarized the experience: “Any visitor to Glasgow can rest body and soul in Miss Cranston’s Tea Rooms and for a few pence drink tea, have breakfast and dream that he is in fairy land.” Another highlighted their being “social centers for business men and apprentices, ladies and ladies’ maids.”

The tailoring of the amenities and décor was meticulous. There were themed colors for the ladies’, general and men’s areas. The ladies’ lunch room was cool white, silver and rose. The Room De Luxe contrasted in its intimate and sumptuous rose-purple and silver painted chairs.

Service was inobtrusive, and of course Cranston chose the waitress uniforms. Customers kept track of their consumption of scones and cakes and simply stated the total at checkout.

But it was the grace notes that made the Willow Room so long recalled in interviews and memoirs. It was described as “a fantasy for enjoying tea.”

The best-known picture of Cranston (1905) is misleading. It makes her look formidable and near regal. She was actually in 1850s costume for an event. One of the most famous architects visiting the Willow, described her as a dark, fat wee body with black sparkling luminous eyes, wears a bonnet garnished with roses, and has made a fortune by supplying cheap clean goods in surroundings prompted by the New Art Glasgow School.”

Both images seem appropriate – elegant and homely, genius and ordinary.

Francis Virginia’s Atlanta tea room

Frances Virginia was the pioneer to tearoom food to match the genius and ordinariness of Kate Cranston’s pioneering of tearoom style.

She built a tea establishment that daily served an estimated one percent of Atlanta’s population in the 1920s. She was an exemplary employer, one of the first to offer benefits and pay Afro-American staff on the same basis as whites. She gave away an estimated million dollars in free food during the Depression.

There are no available pictures of her. Here is her tearoom.

She was part of an entirely new education development that semi-professionalized women participants This was Home Economics, far more than the modern association of it with high school cookery classes. The curriculum that formed in Southern colleges was rigorous and its graduates, including Frances Virginia, were professional dieticians and the equivalent to executive chefs. One historian captures the ethos of its most ambitious graduates being to move into the male world and clean it up.

When Virginia set up her business in 1929, she had already held management positions in hospitals. One was as head dietician for a new program. In another she worked on a major diabetes research project. By 1929, women had the vote so many had so long fought for. She was a builder in the women’s professional and business fields, a very active, visible and influential one.

There was still far too go. In Atlanta, the menu for the grill in its largest department store displayed in the window “Men Only until after 3:00.” That was in the 1950s. One woman recalled that she and her friends always stayed outside the restaurants in their car and ordered curb service.

Frances Virginia’s advertising targeted youngsters, tourists. Workers, sports fans, singles, and families. Her tea room was a friendly host to gays. Alas, while her workers were predominantly Afro-American, blacks couldn’t be customers. Atlanta was racially segregated, with aggressive police and legal controls.

The food: nutrition or moment of pleasure?

There’s one dimension of tea gatherings that seems overlooked: the food. The stereotype image of the tearoom is idyllic, indulgent and sugar-loaded. That reflects a social and income distinction. It’s food for people who don’t need it. If your diet is balanced and well-met, when offered some “refreshment” you are geared to the sweet, flavorful, scrumptious. Empty calories don’t matter. A tea break is mainly an opportunity for topping up. A little cucumber sandwich, a rich chocolate digestive biscuit – oh and leave room for the strawberry tart. What you want is the “momentarily delicious.”

All the legends about high tea and arguments about where it was really and wasn’t low tea come back to this. For the poor, tea time was a meal, centered on basic foods. For the upperclass, it could be a tray of nibbles – low tea, for the table type – or a variety of more filling choices – high tea, early dinner, etc.

The tearooms as contrasted with upmarket tea palaces, offered plain and healthy foods. Their customer base was mainly upper working class women, often younger ones, and lower middle class families. These were largely frugal and with little cash to spare.

Virginia’s menus were nutritionally state of best practice. She offered Southern home cooking of outstanding quality at very low prices. Her biographer came across many customers 50 years after the event, who still preserved the menu. She didn’t neglect “treats.” An instance that stayed in the minds of many of customers decades later was Her Tipsy Trifle, a slightly alcohol-enhanced dessert.

One of her most noted and admired contributions was that between 1932 and 1935, the depths of the Depression, she gave away free over a quarter of the meals she served. This had more than a charitable impact. Commentators noted that she created a ripple effect across suppliers, farmers and distributors. More particularly, she challenged an often stated view that “soft-hearted” women could not succeed in the tough food service business.

Soft-hearted didn’t get in the way of business-practical. She maintained the profitability of her tearoom throughout the Depression. She paid her female staff men’s level wages. She attracted, mentored and often financed the education for a whole community of women.

It’s hard to do justice to this stellar figure. Here is a nice summary of what she and the other leaders of the tea movements accomplished. This was to “nourish the bodies that fueled the next feminist movement for a more welcoming society.”

The new customer base

Women’s published diaries and memoirs from the time are full of small, often touching, appreciations of how this tea room welcoming changed their everyday lives. One of the most-quoted, from 1911, is Kate Frye, a volunteer organizer for a suffrage group: “Came in, had my lunch [in the hotel dining room] in company with four motorists. It is funny the way men come in here, and seeing me, shoot out again, and I hear whispered conversations outside… they might never have seen a woman before – but I suppose it does seem a funny place to find one.” [The emphasis is added here.]

Scattered through her diaries are all the many tea rooms where it wasn’t at all funny to find friends, colleagues, public speakers, rights organizers. The places she names are iconic: The Criterion, Alan’s, Eustace Miles, and The Gardenia. These were the base for a new community of women.

Alan’s Tearoom was owned by Marguerite Alan Liddle. She used her brother Alan as front man and formal “manager.” In 1903, the great Emmeline Pankhurst split off from the mainstream centrist National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies. She established the far more radical WSPU – Women’s Social and Political Union.

Alan’s was a major advertiser in her newspaper, Vote for Women. And in 1909 Helen Liddle who ran Alan’s until 1916 was the first WSPU activist to be sentenced to prison for window-smashing protests. Her hunger strike marked both an increase in official reprisal and militancy. Meanwhile, her brother Alan ran the tearoom while she was in jail.

Tearooms and the WSPU were almost a single identity. The vegetarian Gardenia, Teacup Inn and Eustace Miles were all located within a short distance from the WSPU headquarters. The group that met to begin the campaign of smashing government office windows did so at a prominent Lyons non-suffragist tearoom, in 1911.

New York

In New York the same patterns emerged. Activists set up tea rooms explicitly to attract women to come, share company and in some instances attend awareness-raising and overtly political events. Mary Shaw the actress and playwright used tea and theater to mobilize her community to raise their voices in action, including founding the Gamut Club for them to drop by, fully equipped with gas burners and kitchen; Alva Belmont, the rich Vanderbilt family member, deploying her wealth very cleverly to provide tea places and events to host sympathizers, activists, donors and allies. She made the tearoom a major fundraiser and social center.

In London and New York, tearooms comprised a walking tour of haunts for radical feminists, social activists, actresses, journalists, fund raisers, and organizers. They were not always women-only but it was they who set the rules of admission and they who established privacy and autonomy.

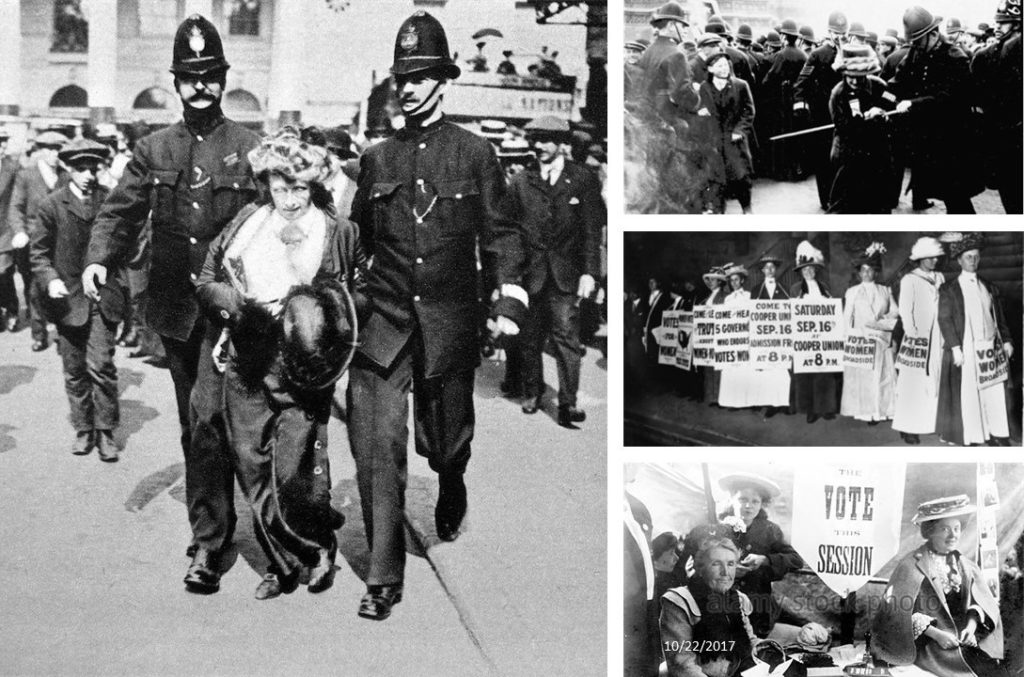

This sounds more idyllic than it often was. Pictures of suffragette protests can appear quaint and even inconsequential.

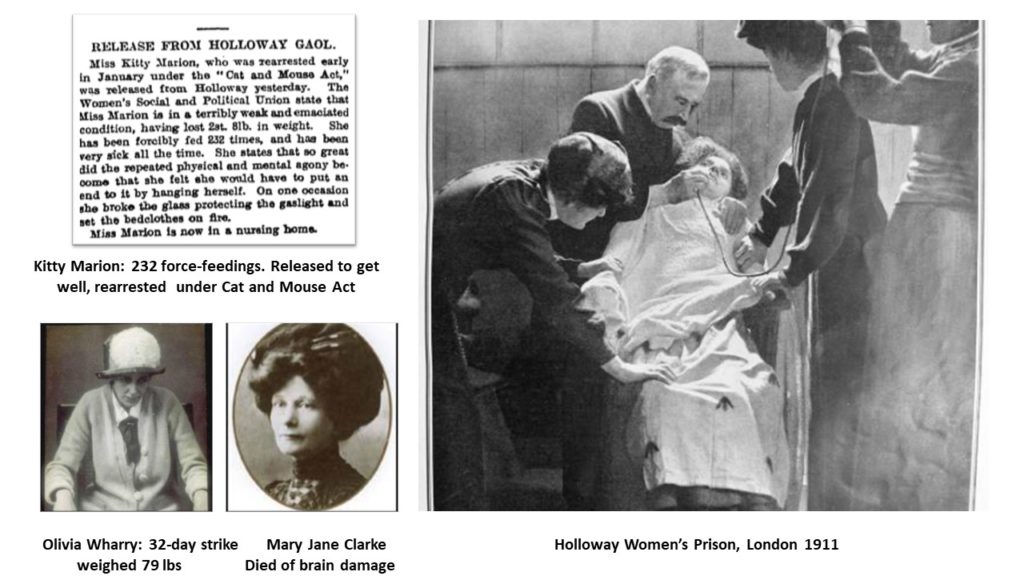

Forget the ornate hats and ladylike dress. Here are just two photos of “ladies” like these. Arrested for protests, many went on hunger strike. They were force-fed by nasal tubes during their prison hunger strikes.

The testimonies are more disgraceful than the picture. London’s Holloway and Virginia’s Lorton jails were torture cells. The British determination to put down these uppity radicals included the 1913 Cat and Mouse act. Women hunger strikers were released from prison and then re-arrested once they were healthy. Olivia Wharry, the women on the bottom left, weighed just 79 pounds on release. Mary Jane Clarke was the first to die, a few days after her own release from Holloway. They had been jailed for stone-throwing.

This sketch barely skims the history of the tearoom as weapon for reform and lever for change. There are so many other dimensions to it: Afro-American tearooms, the very different experiences of women’s rights initiatives in Asia and Africa, especially in the tea growing regions, the tearoom role in reform in Australia and Canada, and many others. The stores need telling.

Throughout the eighteenth to early twentieth centuries, tea was just “a woman’s thing.”

Yes, it was.