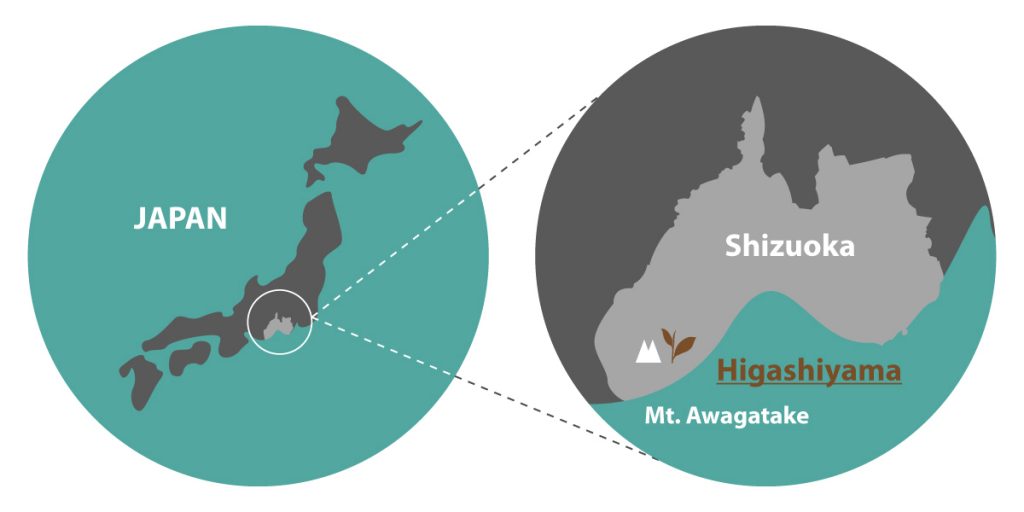

In the foothills of Mt. Fuji lies the village of Higashiyama where Chagusaba agriculture, a UN-designated Globally Important World Agricultural Heritage System, is a way of life for tea farmers.

HIGASHIYAMA, Japan

Chagusaba is an agricultural system in which tea fields are surrounded by semi-natural grasslands. The golden meadows of various types of grass known collectively as “chagusa” or “tea grass” are harvested every autumn, and used for tea cultivation providing natural fertilizer, preventing the growth of weeds, and helping the soil retain moisture. In return, the maintenance of the grasslands by farmers promotes biodiversity in the region.

In 1880, some 30% of Japan consisted of grasslands that provided the rural communities with fertilizer for agriculture (not just tea), food (edible grasses, feed for livestock), energy (firewood), and building material (thatched roofs were once common in rural Japan). Today, the practice of utilizing grass from these grasslands has disappeared with the grasslands themselves, but Chagusaba tea farmers in Shizuoka Prefecture continue to preserve the grasslands and utilize nature’s bounty to win nearly half of the awards handed out for tea excellence. The small village of Higashiyama, where golden meadows of sasa, susuki, and other grasses surround green tea fields, produces 70% of Chagusaba-grown tea.

On this cold, sunny January morning, I had arranged to meet with Akahori-san, the prefectural employee in charge of the Chagusaba promotion. I had explained that I was interested not only in seeing the Chagusaba process, but also meeting the people who practice it. I hoped to uncover more than what the brochures describe as a “traditional farming method for nurturing a rich diversity of living organisms and for co-existence with the environment.” What I discovered is a touching and complex story of tea not found in the official prefectural pamphlet.

As I arrived at the Ippuku Dokoro café to meet Akahori-san, I was caught off guard as two elderly gentlemen came out of the visitor center to greet me. Akahori-san introduced me and we exchanged business cards, or meishi.

In Japan upon a first meeting the exchange is a ritual; you remove your business card from the card case, close the case and place the card on the case with text facing your new acquaintance. You present with two hands and as your counterpart does the same you each remove your left hands from the case and carefully take your counterpart’s card, examining it carefully.

I noticed the roughly dressed Satoshi Sugiyama’s title: “Director.” The corporation was called Chamoji no Sato, Higashiyama (“Higashiyama, The Village of the Tea Character”). This was odd. He certainly looked the part of a farmer, not a corporate director, and government promotion bureaus of the sort that employ Akahori-san do not usually introduce individual companies. The second gentleman, Masashi Hagiwara, was another of the company’s “directors.”

We walked into the cafe, and the staff brought out a cup of fukamushi sencha, its deep green color accentuated by the white porcelain cup. Akahori-san explained the purpose of the meeting as I set up my computer to introduce myself, my company, and Tea Journey as a mobile English-language magazine for tea lovers.

I was anticipating the standard reaction to Western interest in Japanese green tea—interest tinged with skepticism. Despite the rapid growth in tea exports from Japan in the last decade, exports still only make up 4% of Japanese tea production, and growers imagine Western tea drinkers enjoying their green tea only after spooning in mountains of sugar.

Showing the farmers various websites of specialty tea sellers including my own, I wanted to establish that this article was meant for connoisseurs, tea lovers who would appreciate the kind of in-depth knowledge that only they could provide. No sugar-coating. I switched to a different tactic, pointing out that despite a growing global tea industry, Japan’s insular tea market is in decline; tea production, prices and consumption is shrinking as Japanese consumers shift to carbonated beverages and mineral water.

In tea growing regions it is a vicious circle. The decrease in demand during the last 15 years decreased production and prices, and has encouraged the younger generation to leave tea agriculture for other work. The two farmers, Hagiwara-san and Sugiyama-san, were both in their late 60s. When I asked how many younger farmers there were in the village, they started counting names on their fingers. Most of the 120 family farmers were in their 60s; a generation below has half as many farmers, and there are fewer than a dozen in their 20s.

I’ve visited many villages like this, I mentioned. In one area, participants in the local “Young Farmer Development Program” were mostly in their 50s.

As he listened Hagiwara-san then took a bag from his pocket. He emptied its contents into a tea pot, revealing exquisitely shaped, evergreen-colored, hand-rolled sencha called “temomicha”. He had won a Silver Medal at the National Tea Competition with this tea. As the needles unfurled, we started talking about the difference between Japanese descriptors for tea, and Western adoption of wine language for conveying a tea’s flavors.

In Japan, business in every industry begins with face-to-face meetings over tea. Green tea is something you serve to guests as a demonstration of hospitality, to welcome a guest. The best teas, award-winning temomicha, are rarely offered on the market because they are kept in reserve for special meetings and gifts.

As we sipped the golden liquor from the temomicha, I looked down at the business cards laid out neatly on the table. “I noticed your card is from a company and not the cooperative,” I politely mentioned.

“This company was created to promote Higashiyama tea,” Sugiyama-san replied. We talked about how in the usual supply chain, the three cooperatives that represent the 120 family farms buy the tea from each of the individual farms, process the leaves together at their respective coop factories, and sell it in the larger Shizuoka markets as well as directly to finishing factories/wholesalers. Higashiyama’s tea leaves are then likely blended with teas from elsewhere aggregating as the manufacturers further down the supply chain engage in creating their own blends.

Chamoji no Sato was established to promote Higashiyama’s tea and the Chagusaba system. It was financed by 76 families from the village who pooled ¥6 million yen ($50,000) for starting capital. They are the shareholders of the corporation, which sells three-leaf rated Chagusaba-made tea under the Higashiyamacha brand name promoting both Chagusaba and the village. To qualify for the three-leaf rating, leaves harvested from farms must have at least a 1:1 ratio of grassland area to tea fields. Farms are managed separately by individual landowners and not all of the farms in the village qualify for the three-leaf rating.

We next drove to the top of Mt. Awagatake in Sugiyama-san’s van to take in a view of the entire village. We passed a woman in hiking gear on the side of the road waiting. Mt. Awagatake has a number of hiking trails that attract nature enthusiasts. A bus comes to the café a few times a day, and hikers depart from there to get to the summit where the tea character and another visitor center is located.

As we passed tea fields and grass meadows, Sugiyama-san explained that the Chagusaba system was not invented solely for the cultivation of tea, but has been a traditional practice for farmers in the area. In the last century as tea cultivation took over, maintaining the grasslands became integrated into the seasonal cycle of tea farms. It was only recently, in the early 2000s, that scientists began to recognize that this traditional farming method was contributing to increased biodiversity in the region. New signs now dot the village indicating what kind of species (some endangered) of plants and animals exist in the region. At one point, Sugiyama-san stopped his van in the middle of the narrow road and pointed out a mother-child pair of nihonmushika, a native goat-like antelope that was hunted to near extinction in the mid-20th century.

While there is not much field activity in the winter, some of the farmers were still laying down the dried grass, cut into small pieces. Everyone I met was in their 60s. One elderly couple I spoke to pointed out their fields—the wife was laying down straw on a level field, and her husband was doing the same on a sloped field nearby. It would be more efficient if they had one connecting field, I noted. “Yes but then we could only grow one kind of tea leaf.”

The woman in her 70s was using a shredding machine to chop up bundles of susuki grass, each weighing about 10-15kg. She was too shy (despite having her face covered with a mask due to the cold) to have her photo taken so went off to a shed and asked Hagiwara-san to be photographed putting the grass into the chopper. She came back and offered us mikan, a kind of Japanese citrus, removing her mask to apologize that she had only a few to offer.

During a visit to one of the cooperative tea factories, Hagiwara-san explained that the factories of the three co-ops in the village were among the largest in Japan. He was trying to sound impressive, but then added, “the machines are getting old though.” Two shifts of four farmers take turns operating the factory during the harvest season. I mentioned it is amazing such a large facility can be operated with so few people. “With the decline in prices, we discussed whether it can be done with three people instead of four,” laughed Sugiyama-san in reply.

On our return to the café from the tour I asked “how much do you export? You know that the average price of exported tea is rising, right? Buyers outside of Japan want the premium leaves.”

“None.”

“None?”

“Yes. None. We don’t export and we don’t know of anyone exporting Chagusaba-grown tea,” said Akahori-san. The farmers understand how to sell in the domestic market—the supply chain here is an old system—but not to other countries. “The business relationships don’t exist,” he explained.

Let’s see if we can’t solve that problem, I said.

Tasting Notes

The Higashiyama Village, like much of Shizuoka Prefecture, mainly produces fukamushi tea, a subcategory of sencha in which the leaves are steamed for a longer time. The longer steaming time (generally 60 seconds, but this may vary quite a bit depending on the leaf being steamed) results in the leaf being broken into much smaller pieces than normal sencha, and a tea leaf that steeps quick and strong, is deep green in color, and opaque due to the small bits of leaf.

This processing method was developed in the 1950s and 60s in the Makinohara region of Shizuoka on the flatlands closer to the sea in order to produce a better tea from the less tender leaves. Flatlands receive more sunlight allowing leaves to grow faster but as a result new leaves lose their tenderness faster. The stiffness of the leaves makes the rolling that releases the leaf’s flavors more difficult, and therefore more raw grassiness remains in the leaf. Deep-steaming helped to solve this, and created a deep green color that quickly became popular in Japan as more and more of the consumer population began to afford higher grade tea in Japan’s rapid economic development during the 1960s.

To illustrate the difference between Fukamushi Tea and Temomicha:

Steeping Notes

The leaf will steep quickly and strongly, and changes quite a bit in flavor depending on water temperature. Start with 5 grams, 250 ml of water, and adjust from there.

For this tasting, I started with a temperature of 70˚C/158˚F degrees, and steeped for 60 seconds. This steeps a fairly strong tea. 70˚C is a good temperature for spring-harvested, first flush fukamushi tea creating a full-bodied steep balanced between astringency and umami flavors.

On a second steeping, the leaves are already primed and require a very short in-out steep (10 seconds, slightly more time than it takes to fill the pot). As you have likely extracted most of the umami flavor out in the first steep, use a higher temperature (80-90˚C/176-194˚F) to draw out a stronger flavor. Subsequent steepings require 45 seconds.

Tea Market

Get More Value from Your Tea: BRU Maker One

+41794574278

Jacque's Organics

(647) 804-7263

Great article, also really enjoyed the pictures as well. I’d be eager to try some tea from Higashiyama if any tea vendor in the States is able to pick any up and sell.

Great article, makes me want to travel to hike and drink tea locally. Also to wish for a US distributor.