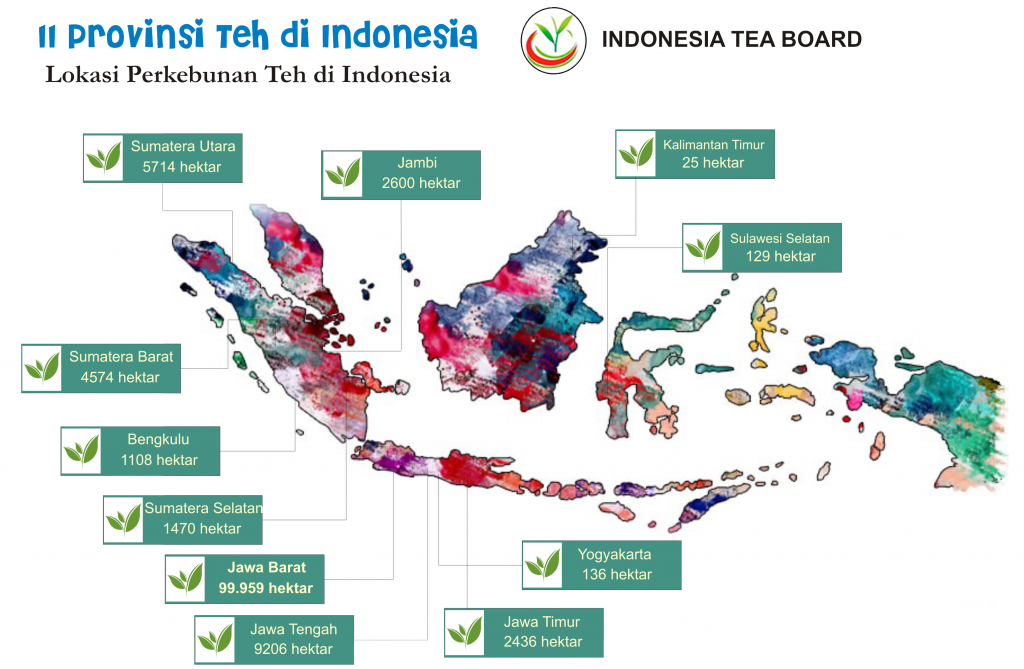

Indonesia’s Principal Tea Growing Regions

Anchored in the warm, sparkling waters of Southeast Asia, Indonesia is the world’s largest island country, boasting between 13,000 and 18,000 islands depending on the swell of the ocean tides.

This expansive archipelago is formed by volcanic activity and intense geological forces, thanks to the country’s perch on the Ring of Fire. The landscape is a diverse and dramatic one. Vast coastlines give way to fertile valleys, forested mountains, and the occasional volcano; there are over 400 volcanoes, 150 of them active, in Indonesia. Waterfalls adorn the lush rainforests, a testament to the warm, abundant rains.

Camellia sinensis finds itself right at home in this tropical landscape. Mineral-laden, slightly acidic soils enrich the land, while the hot, humid climate offers abundant amounts of sunshine, and rainfall. It’s a suitable terroir, if a little too comfortable for the resident tea plants. Without the obstacles of cold temperatures, extreme altitudes, or frost, Indonesia’s bushes grow rapidly, and flush year-round. In the absence of a winter, the plants do not have a period of dormancy, and there is no typical resting season for the plants that is practiced in Indonesia, as is sometimes done by growers in China or Taiwan during the summer.

As a result, there are few seasonal variations for Indonesia’s teas. This is in contrast to areas like Japan or Darjeeling, where extremes in temperature and growing conditions throughout the seasons create drastically different profiles with each harvest. There is no Indonesian equivalent to Darjeeling’s first flush, or to the coveted Japanese shincha, when the tea plants exhibit a brilliant first harvest after months of stockpiling nutrients during the winter.

Instead, the value of Indonesia’s teas is in consistency. Because tea makers constantly harvest tea, and growing conditions vary little, there are relatively few differences in the flavor profiles of each batch of tea. This means that tea makers can more quickly identify the distinct character of their leaf material, and focus on developing the optimal styles of crafting for their teas. While the highly seasonal nature of other regions’ teas can be exciting, this also allows more room for error, and there are both spectacular and disappointing harvests. Indonesia’s tea makers are remarkably consistent, often crafting just a handful of teas, but with a mastery that comes from considerable practice.

While a majority of Indonesia’s tea production is geared towards commodity tea, its specialty teas offer an exciting new region to explore, influenced by the distinct terroir and experiences of its tea makers. Indonesian teas are a bridge between the aesthetic of China and Taiwan’s tea cultures, emphasizing complexity, sweetness, and a distinct character, and the more brisk, bold, and consistent character seen in similar regions like Sri Lanka and the Nilgiri tea growing regions in southern India.

Indonesian teas often have a mineral character with a slight briskness or astringency, providing a “clean” or “pristine” feeling in the profile. This mineral character sometimes manifests as a sweeter, earthy note, or as petrichor or wet stone, perhaps an echo of the rich, rain-soaked volcanic soils of their origin.

Tea Market

Get More Value from Your Tea: BRU Maker One

+41794574278

Jacque's Organics

(647) 804-7263