![Temi Tarku, sikkim[1]](https://teajourney.pub/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Temi-Tarku-sikkim1.jpg)

Geographic boundaries are of little concern to the ancient undulating landscape. The unique environment has both nurtured and challenged any living thing that dares to enter its realm. The inhabitants are stalwart and enduring. Hundreds of unique plant species are found there. Himalayan firs, oak and birch trees make up the dense forests. Rare orchids and rhododendron add a spark of color to the hillsides. Citrus fruits impossibly thrive in the rocky soil and cool temperatures, and verdant tea gardens cover the slopes and plains in a blanket of green.

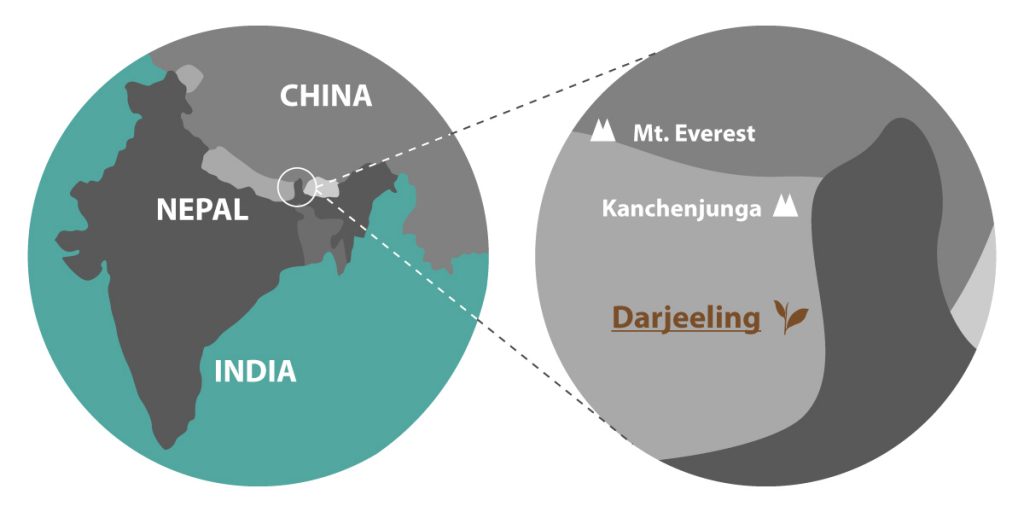

Parts of Nepal, Tibet, India and Bhutan are within view of the majestic icon whose five peaks look down on famous tea gardens in Darjeeling, Sikkim, Kalimpong, Pedong, Ilam, Hile and Taplejung.

It seems an unlikely place to grow tea. These gardens cling to the hills surrounding the mountain with its ever present swirling, blowing cap of brilliant snow.

The steep slopes are often precarious, even for sure-footed Sherpas. Landslides are common, especially when it rains. The entire area is prone to earthquakes. Wild tigers, boar and other deadly predators still roam the forests. Temperatures in Darjeeling can reach a low of 0◦ C (32◦ F). While Kanchenjunga reaches an elevation of 28,169 feet, tea gardens in Taplejung, Nepal are perched at 7,300 feet and in Darjeeling, India, as high as 6,700 feet. Compared to tea cultivated at lower elevations, the “China bush” of the Himalayas grows much slower resulting in much lower yields.

According to tea producer and trader Rajiv Lochan, it is the stressors of this environment that give the teas their unique characteristics. Tea gardens on the North-facing slopes are exposed to the unrelenting fresh, cool air descending from the mountains — one of the key factors that contribute to their special aroma and flavor.

Tea planting dates to the British starting in the mid-1800s. Smuggled seeds that sprouted enroute from China were first planted in Darjeeling in 1839, though actual production followed a few years later. There are stories of earlier plantings. Kalimpong (which was part of Bhutan at the time) was a key trading hub connecting India and Tibet through the Jelepla and Nathula passes. Because of the natural geographical advantage, and its proximity to Lhasa, Tibet, it is said that some industrious Chinese businessmen set up tea production in the Kalimpong area to supply the Tibetan market in competition with suppliers in Yunnan. These stories are now recorded only in the memories of a few local elders, but remnants of tea gardens can still be found in places like Pedong.

While Kanchenjunga’s west half is in Nepal, the east is bordered by Sikkim. A sovereign kingdom until 1975, Sikkim is unique for its environmental diversity. It has the lowest population of all Indian states, and nearly 25% of the area of Sikkim is within the Kanchenjunga National Park boundaries. Temi tea estate in Sikkim was planted in 1968 in part to accommodate an influx of Tibetan refugees. The 500 acres of tea trees makes it only tea estate in Sikkim that produces quality orthodox teas, mainly for export.

In Nepal, tea plantings date to 1868 with a gift of tea seeds from the Chinese Emperor to the Nepali Prime Minister. The first tea factory in Ilam was built in 1868, according to Udaya Champagain, head of the Gorkha tea estate. “One unique feature of teas from this area is that the bushes are relatively young. Also the land was completely virgin forest before planting tea bushes,” he said. Champagain feels that these factors, combined with the pollution-free, organic environment and the cool, humid mountain air distinguish these teas from all others.

More recent plantings in Nepal began in the mid to late 1980s. Mist Valley estate in Ilam, the main producing region, was first planted in China clonal bushes in 1988. Their first measurable harvest wasn’t until 2004. Suresh Limbu explains that “Topography is similar to Darjeeling but Nepal teas have their own unique distinctions. Special attributes can include a mellow flavor with floral, fruity, muscatel sweetness.”

Depending on weather, there are generally four harvest seasons. The new shoots of first flush are plucked around the third week of March through the end of April. Second flush teas are harvested from mid-May to mid-July. Monsoon teas get picked from the 16th of July to the end of September. The final harvest extends from October through the 15th of November and is known as the Autumnal flush.

Unlike their neighbors in Darjeeling and Sikkim, many of the tea gardens in Nepal were started by collectives of farmers who pooled their land for the common good. The idea for the Kanchenjunga Tea Estate was founded by Baskota (first names only are common), who was inspired by a visit to the tea gardens of Darjeeling and the higher standard of living the workers enjoyed. Ultimately he was able to persuade fellow farmers to join together to improve their quality of living. One of the newest gardens, Pativara Tea Cooperative, is in Taplejung district and is part of the Central Tea Cooperation Federation. Its slopes greet Kanchenjunga each morning at an elevation of more than 7,300 feet. The cooperative produces only green tea for sale in the local markets.

Other gardens belong to marketing cooperatives like HIMCOOP (Himalayan Tea Producers Cooperative). Many of these Nepal gardens produce the traditional black teas but some have gotten very creative, even innovative in the teas they are producing, including white teas, oolong teas, and steamed (Japanese style) green teas. The Gorkha Tea factory received organic certification in 2009. Some of its teas are so unique that specially skilled pluckers and tea makers are required to make their signature gold and silver teas. “Only 50 kilos of these teas are produced in the entire year,” says owner Udaya Chapagain.

The jewel of the foothills remains Darjeeling.

Known as the “Land of the Thunder Bolt or Thunder Clap” in Nepali, much of the tea growing area of the hills, up to the Teesta River, was once part of Nepal. In fact, most of the people in the area, and certainly many of the tea workers, identify themselves ethnically as Nepali or Gorkhali.

Darjeeling possesses unique features which are apparent in the teas. Elevation of tea growing ranges from 1,500 to over 6,000 feet. Darjeeling tea growers talk in terms of the “muscatel flavor” and the “bouquet” of these teas.

“Tea bushes growing on the slopes of the cool, humid but well drained gardens thrive in the rich soil,” says Nibir Bordoloi from Glenburn tea estate. From the original planter’s bungalows, now restored to a luxurious boutique hotel, one can sip a cup of tea that was made only hours before, while watching the sunrise on the mountain. As the first light of the day slowly expands from the golden peaks, it brings renewed vitality not only to the nearby town of Darjeeling but to all the green tea leaves that drink up the sun’s rays. Glenburn has always made traditional Darjeeling teas with full body and notes of citrus. Numerous pomelo trees grow on the property as well as oranges. Today the factory makes several “specialty” and signature teas that go beyond traditional techniques. One such tea, nick-named “spring in a cup” by one of their buyers, has multi-layered complexity that evolves with subsequent infusions, ranging from a gentle spring breeze and flower buds at first sip to citrus and green banana in later steepings.

Glenburn was founded in 1859 by a Scottish tea company while the Steinthal tea estate was established by a German in 1852. One of the oldest estates in the region, Steinthal is a sprawling estate at the top of the production elevations. Located just near Darjeeling, these teas are typically light and aromatic. Flavors range from floral and fruity in the first flush to deep and mellow in the autumn. A stay at their Singtom bungalow usually includes a visit to the 360 point where one has an unobstructed view of Kanchenjunga and many surrounding tea gardens.

Tea buyers and lovers that frequent the hills will tell you that each of the gardens produce a distinctly flavored tea. In truth, one can take a lifetime learning to recognize a garden by blind taste. Now, with so nearby gardens producing wonderful and unique teas, one may need to live as long as the mountain itself to experience all the wonderful tastes and aromas that sprout from this enigmatic and radiant region near the top of the world.

Tea Market

Get More Value from Your Tea: BRU Maker One

+41794574278

Jacque's Organics

(647) 804-7263

So beautifully expressed; thank you.

Thank you Ashok.

Informative, Interesting, intriguing and makes for quality reading. Nice article.

Most eloquently written article. Describes Tea, Terrain, Tribes and the Territory in the most beautiful way.

Thank you Madhav and Raju. Hope you approve and more people will want to visit. World Tea Tours will bring the Tea Tour of India to Darjeeling again in October 2017. All are welcome.

I really enjoyed this article – it’s just the kind of information that helps me increase my ability to appreciate tea. I can’t imagine having a tea that is only a few hours old!

So beautifully expressed; thank you.

Thanks for sharing such information in detail.