A seemingly innocuous question sent James Ajoo, from Chennai, South India, on a quest that, 14 years later, is finally showing light at the end of the tunnel. In 2007, James Suthan Ajoo was studying Biblical Theology in Oregon, in the United States, when classmates asked him about his unusual surname, ‘Ajoo.’

He had no answers, so he turned to his father, who said, “It’s a Chinese name.” James, 37, was born and raised in Chennai. His family could be traced back a few generations, and as far as he could tell, there was nothing in their appearance to hint at a Chinese connection, nor was there any known association with China. But James remembered stray anecdotes, family lore that had always mentioned a Chinese ancestor. Now, he felt the need to know more, check its authenticity, and make sense of how and why he had a Chinese ancestor. He turned to Google. “I found a lot of Ajoos in Korea,” he says. His search for information on the name Ajoo and someone who carried that name eventually led him to tea.

For three years between 2007 and 2010, he had tried to find a link to a distant Ajoo who could be his ancestor. His family was from Munnar, and his grandfather had worked in tea. During his research, James arrived at a history of the Nilgiris.

The Nilgiris in South India have a history quite different from either Darjeeling or Assam; its tea story comes with an unusual Chinese connection. In the 1850s, W.G. McIvor, who set up the Ooty Botanical Gardens, wrote to the superintendent in Madras asking for 500 convicts. He needed men to work with him in cinchona cultivation (grown for quinine which was the antidote to malaria). McIvor’s request was timely as the prisons in Madras were running full. Prisoners captured during the Opium War had been brought from the straits of Singapore and needed to be housed somewhere. And so, 556 PoWs from Singapore, Malacca, and Penang arrived in Naduvattam in the Nilgiris. They worked on cinchona but also on the fledgling tea cultivation that had begun. It is assumed that they remained here and became part of the local population. James Ajoo heard this story and now wondered if his ancestor was one of these 556 PoWs.

It was in 2010 that he had some luck. Looking through the British Library’s online archives, he found out that on 15th March, 1851, the streamer Lady Mary Wood had docked in Calcutta, having left Hong Kong a month earlier. It was carrying a cargo of tea seeds and tea saplings. The passenger list included Scotsman Robert Fortune and eight Chinese men, and among them John Ajoo.

“I didn’t like history growing up,” confesses James. “But I had a lot of questions. There were other Chinese too. In all, Fortune brought 23 Chinese to India between 1850-56. The eight who came with him on the Lady Mary Wood were sent to Pauri, where tea planting was already in progress.”

Pauri is in the foothills of the Himalayas, in present-day Uttarakhand state. About 200 kilometers from here is Saharanpur, where the East India Company set up the Botanical Gardens way back in the 18th century. It was to Saharanpur’s garden superintendents that Fortune’s tea seedlings were sent. Work in tea cultivation and planting was already underway, and Fortune now brought the eight Chinese there to teach the natives how to make tea.

James was now approaching his story from its two ends, that of Fortune and the arrival of John Ajoo into India and backwards from family history and lore, to see if they would indeed meet. The middle was a large and undocumented mystery, although the story of Indian tea and the AJoo family history had begun to cross.

Research proved difficult as the British took back most of the records with them when India became independent. Plenty of other documentation was destroyed. James had to rely heavily on oral history.

Pauri is in the northwest frontier of India. James lives in the south, and his known ancestry was to Munnar in Kerala. How did John Ajoo arrive in Kerala was a big question? “To fill those gaps … I have been on that journey,” says James.

James’ father, Stephen Ajoo is a pastor. Growing up in Munnar, he had interned briefly in a tea factory before leaving the hills for the coastal city of Chennai in the south. With that, the family’s connection to tea ended. For James, Munnar was the place they visited on family trips. “It was always about, this is where my father grew up, and his father before him,” he says. As he progressed through his family history, James turned towards Munnar for clues.

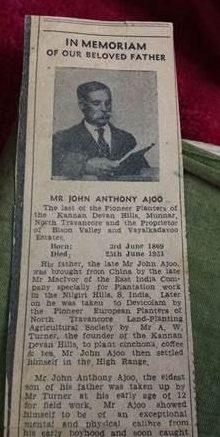

There is a section of tea fields in Munnar that locals refer to as the Chinaman’s Field, next to the Talliar Tea Estate (still standing). Talliar was planted in the 1880s, and James was able to speak to people here, including the manager at Talliar. It was Munnar where he found more information and more pieces of the jigsaw. The CSI Church in Munnar had a death record for John Antony Ajoo, which indicated the year of birth as 1869. He was the son of John Ajoo.

In Munnar too, James came by a booklet that narrated the story of the family of GT Thangaswamy. This little family history narrated how the Munnar tea industry came to be and how the Thangaswamy family was brought to Munnar by the East India Company. It also mentions Thangaswamy’s friend, John Antony Ajoo, the Chinaman’s son. Members of this family confirmed that John Antony Ajoo and his son James indeed lived in Munnar as known from their family lore.

But James still didn’t know how John Ajoo, who was last seen in Pauri, Uttarakhand, arrived in Munnar, Kerala.

Journalist Nina Varghese grew up in the Nilgiris as a planter’s daughter. She reported the Chinese’s story in the Nilgiris, recounting that in the early 1860s, the Nilgiris officials were keen to replicate Darjeeling’s tea cultivation’s success. They sought the help of the Chinese tea makers, the very same guys that Fortune had brought. They were offered native tea makers from Pauri, trained by the Chinese but refused. Upon insisting that they too receive the Chinese tea makers’ services, two of Fortune’s original eight were sent to the Nilgiris in 1863-64. One of them was John Ajoo. His arrival is also documented by S. Muthaiah, a writer of scholarly repute, in his book, A Planting Century. The book was commissioned by UPASI, the body of planters of south India.

It appears that John Ajoo worked in the Nilgiris, assumedly married a local woman, and had a son, John Antony Ajoo. But Munnar is not in the Nilgiris. It is part of the mountain ranges known as the Western Ghats that traverse the western edge of the Indian peninsula, of which the Nilgiris are no a part. As the Nilgiris developed their tea plantations, the British went further in their explorations for suitable land. Munnar was deemed suitable. Its forests were cleared to make way for tea. In 1877, Henry Turner and his half-brother A.W. Turner began planting. It was Henry who asked John Ajoo to go to Munnar. John Ajoo left for these hills along with his family. In Munnar, he farmed his own a patch of land (the Chinaman’s Field) not far from Talliar estate, which was part of the Turners’ holdings. He lived there till his end, never returning to China.

His son, John Antony, continued his father’s legacy, becoming a planter of note. His death record indicates that he was 82 (1951) when he passed away. The family line continues with James Ajoo, Kenneth Solomon Ajoo, Stephen Ajoo, and James Ajoo.

Along the way, the Ajoos turned from plantation work to church. But as James says, “Tea runs in my blood as does faith. Trying to connect those two is a priority in my story.” His research indicates that John Ajoo was already a Christian, a Catholic Christian. And that these Chinese, all connected to the Catholic belief, were a minority in their country. They were practicing Christians from the Hwuy-Chow province (Robert Fortune mentions that Hwuy-Chow was closed to Europeans, and only the Jesuit missionaries had previously visited.)

The research is not yet complete. The last time we spoke, James was in the Nilgiris, looking for more records, more answers to complete this story. From Hwuy-Chow Foo, a tea-growing district in Anhui China to Pauri, the Nilgiris, Munnar, and Chennai … the Ajoo family story traverses an untold chapter in the history of Indian tea, a road James Ajoo is trying to retrace, “to say I landed my feet where my ancestor had walked.”

His family has been a source of quiet support, “My father says it’s not his calling but that it’s mine. I have to do this.” Remembering childhood trips to Munnar, he says: “I would think, look at this place, tea fields everywhere, so many teas, I could live here all my life. And now, I find that my ancestor indeed lived here and grew tea. It gives me goosebumps.”

Tea Market

Get More Value from Your Tea: BRU Maker One

+41794574278

Jacque's Organics

(647) 804-7263

I wonder what a DNA test would tell about your background as well?

Taking a DNA test did strike my mind but the question I came up was what would I refer my results with? May be in the future if GOD willing.

Just this Good-Friday I made a remarkable find about a 150 years old reference to the Chinaman John.

Thanks for the comment.

DNA is one method, but what belief system you believe in would be more fruitful !

Aravinda, what an amazing narrative !! Thank you for researching this, loved it !!

Thank you, Ranjit!

Nice Article. Is it possible to get the contact details of Mr. James ? I am looking for some reference purpose.

Regards,

S.Kumar

kumar@xploreindo.com

You can contact me via email jamesajoo@gmail.com

Interesting story. I would like to know any references to Ceylon tea and tea growing here.

Ziard Caffoor , Kandy Sri Lanka.

What an incredible story. Somethings do drive one to explore the past: just to know. Roots!

Thanks a lot for sharing your history and the journey of tea to munnar.