Story by Hongkuan Huang, courtesy of Puer Magazine

Pile-fermentation is a modern technique to enhance microbial activity, which is the secret to producing Shou Puer.

The 45-day process involves moistening large stacks of sun-dried raw tea leaves. The leaves are piled high and carefully monitored to produce dark composted tea, which is pressed into cakes and sold in round bamboo containers.

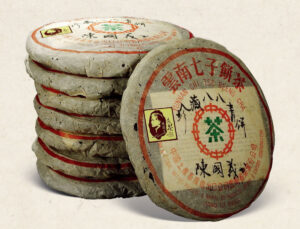

A tong is one common unit when purchasing puer cakes, often by collectors rather than for immediate consumption. One tong consists of seven cakes, usually wrapped in bamboo leaves. One piece of puer cake is also known as a qī zǐ bǐng (七子餅, seven-Liang cake), a term derived from its most common weight (357 grams).

Puer is generally sold in units of seven liang (one liang weighs 50 grams). When shopping at a Chinese tea market, merchants price their tea by Liang rather than grams.

Making puer

Tea processors begin the process by creating large-scale incubators for the microbes – a mix of Aspergillus niger bacteria and Blastobotrys adeninivorans – that impart the pleasant forest-floor flavor of Shou Puer. Each plays an important role in converting tea polyphenols into bioactive compounds that are beneficial to health. Controlling moisture content is critical. The bacteria thrive when water content is 30% or less and prefer a slightly acidic pH value of 5 to 6.

In the 1950s, a few Hong Kong tea houses discovered that controlled fermentation, completed in as few as 45 days, removes the bitterness in green puer that previously required more than a decade to age. Maintaining the very high humidity necessary for natural aging for prolonged periods was very costly, and the results were unpredictable. The new process of spraying water on the tea in large fermentation rooms and frequent turning proved challenging from the onset but saved considerable space and time.

In 1973, several Chinese experts were sent from Yunnan to Guangdong Province to study pile-fermentation. Within two years, they introduced several refinements that made it possible to produce Shou Puer on a mass scale. By the 1980s, tea processors had refined these techniques to eliminate defects introduced during fermentation. Today, the process is well-known and relatively mature. The introduction of pile-fermentation generated large profits as pent-up demand for these healthful teas soared.

Precise preparations

The entire surface of large warehouses must be prepped before fermentation. Tea processors start by covering the cement floor to a depth of one centimeter with broken leaves of Shou Puer and fannings (dust). Water is then sprayed liberally to soak the fannings. Every two to three days, the processors water the fannings until they no longer smell. By then, the cement floor has turned charcoal black. The floor is rinsed and dried, leaving a uniform layer of starter material on which the leaves are piled.

The tea is arranged in windrows. Temperatures immediately increase as the bacteria multiply, remaining at around 50°C (122°F) for the first 35 days before gradually decreasing to room temperature, a pattern consistent with rapid propagation of fungi and yeasts.

Throughout the process, the tea leaves are turned to achieve consistent fermentation and prevent the formation of compressed tea blocks.

Here are the major steps in the process in detail:

1. Moisten the sun-dried crude tea

The amount of water applied is critical and subjective based on factors such as leaf quality, ambient temperature, humidity, and the quality of the water itself. Tea processors spray water from 30% to 50% of the crude tea’s total weight on top of the pile. For every 100 kilos of tea, workers spray 30 to 50 kilos of water. When fresh tea leaves are used, less water is needed; if the leaves are stale and dry, more water is sprayed. The piles must be moistened evenly over a short period to ensure the leaves ferment at roughly the same speed.

Wetted teas being piled up

2. Piling the tea

The windrows are initially 50 to 70 centimeters high. The coarser the tea, the higher the tea is stacked. The tops of the piles are then flattened, and the sides sloped. A small pile might weigh 100 kg, and the largest pile can weigh 10 to 20 tons.

3. Covering the pile

During the period when the bacteria are growing rapidly, the covers are removed, and the tea is turned every two weeks to maintain a stable temperature between 50°C and 65°C (122 – 149°F). The piles will be turned four or five times, depending on the characteristics of each particular batch. Every time the pile is turned, the height of the pile drops by about 60 centimeters as excess moisture is released.

4. Turning

The moist leaves form clumps that can settle into dense blocks. Tea processors break these clumps apart using special machines and then scatter the leaves into existing piles to maintain a balance of temperature, humidity, and air permeability. Failing to keep a close eye on the process results in excess carbonization, which ruins the tea flavor. This is known as “pile-burning,” and it results in scrapping the entire pile.

5. Furrowing

Workers must furrow the pile daily to facilitate drying and reduce temperatures as fermentation nears completion. Timing is key – if they start furrowing prematurely, the tea will not be fully fermented, resulting a thin taste; furrow too late and the result is excessive fermentation. Ventilation is not needed in the fermentation rooms during the first half of the process, but toward the end, every window and door should be open so the teas will dry quickly. Due to constant turning, the height of the pile has now been reduced to 40 centimeters.

Around day 35, the pile’s temperature drops to 35°C (95°F). That is the time to cool down the tea. It takes 3-5 days of furrowing to reduce the leaves’ water content to 14%. This is a natural and gradual process. Baking, roasting, and sun-drying are prohibited when drying the puer tea.

6. Airing

After 45 days, the crude tea no longer needs to be furrowed. It is spread flat and aired until it reaches room temperature and water content returns to normal.

7. Separation

Processors then use machines to separate stones, chaff, old stalks, flowers, fruit – anything that is not puer is removed from the pile.

8. Sterilization

Tea factories with high production standards sterilize the tea to deactivate microorganisms before compressing it into 357-gram cakes or other desired forms.

9. Steam-pressing, packaging

Freshly processed Shou Puer tea exhibits a strong smell. Many tea factories store the tea for 1-3 years to dissipate the scent before compressing it with a seal of authenticity embedded in the cake and wrapping it for sale.

Not Quite Right

It is very easy to introduce odors and odd — even disturbing — flavors while processing puer. Most can be traced to failing to notice some details during the pile-fermentation process.

Here are four tell-tale tastes that indicate the tea was poorly processed:

Sour taste —This was a common complaint several years ago, caused by insufficient fermentation. The tea processers’ rationale is to leave some room for the Shou Puer to age naturally rather than be perfectly done. But undue compression suppresses microbial growth, leading to sour or thin-flavored tea, and sometimes both! Low temperatures are another cause of souring in the leaf pile. Souring is a flaw that may require several decades of aging to remove.

Numb tongue — Numb tongue and a dry, sticking sensation in the throat is caused by excessive fermentation, contrary to previous under-fermentation. The first several cups of this tea may taste mild, but it gradually makes your tongue feel numb and your throat dry. Evidence of this flaw may be found at the bottom of the puer cake, which will appear black due to carbonation from excessive fermentation.

Muddy cup — the smell of mud could be caused by using crude tea that was cooked by machine-baking rather than sun-drying. If teas are over-baked, the bacteria used for post-fermentation might be killed in the process, too. Then, during pile-fermentation, teas are subject to a humid and hot environment over a long period of time, generating unpleasant notes.

Thin flavor — Inferior raw materials make the normally dark tea too light in appearance and taste. Blending before fermentation is essential: I prefer crude teas that are handmade and sun-dried from mountain tea gardens; and I personally recommend blending 30% of the crude tea produced in Lincang with 70% from Menghai (both are sub-regions in Yunnan provinces). This blend insures abundant and balanced characteristics in the finished tea.

Retold with permission from Puerh Magazine (issue 10, 2012). Chinese language Copyright 2016 Puerh. Puerh Magazine, a strategic partner of Tea Journey, is the most reputable Mandarin tea magazine on the subject of puer tea, based in Kunming, Yunnan province, China.

Story Retold by Si Chen

Tea Market

Get More Value from Your Tea: BRU Maker One

+41794574278

Jacque's Organics

(647) 804-7263

Xie xie Si Chen for translating this highly interesting article!

Morten you are so fast! Thank you my dear friend. Wish to meet again in Berlin or Beijing!

This is the best english description of this mysterious process I have seen online.

Well done

Thank you for this in-depth explanation, and helpful photos.

Still many ‘mysteries’ left within this process….

Good Shou is easy to taste, hard to find.

With the advent of ‘plantation Puerh’ (sic) Shou Puerh is flooding the market.

Seed grown, Tree Tea Puerh is still the real deal, and superior to bush Puerh.

Studying the process is going to help a lot of people understand Puerh more.

And hopefully lead to greater awareness of Tree vs. Bush Puerh….

Absolutely – many connoisseurs set their eyes on wild trees but it is really difficult to source from growers consistently even if you have a trustworthy business relationship – they are just too popular. By ‘plantation’ or ‘bush’ puer, I assume you are referring to trees that has been planted in large quantity for commercial harvest, which are locally referred as small-tree tea. Within this category, you have basin-area plantation (‘taidi’ or ‘bazi’) tea and high-mountain plantation (‘shantou’) tea. Most high-mountain trees are still plantation/bush tree, and within all the high-mountain trees, the most desired are big-tree tea or ancient-tree (‘gushu’) tea (2-5m tall), then old-tree (‘laoshu’) tea (wild trees undergo dwarfing procedure), and then high mountain plantation (the majority of organic puer are from this category; planted in tight rows). Big-tree or ancient tree teas are the only type that is not small tree tea. The growing area of big-tree region is only a fraction of 7% of all tea growing regions in Yunnan.

In the upcoming Aug Harvest Review issue, our taster based in Kunming has in fact chosen big-tree Puer from Yiwu region to be his personal favorite.

what would the trait of *fishy* fall under in the four traits of poorly fermented tea?