Mount Wuyi, Fujian Province, China — The Nine Bend River (Jiuqu Xi) is a masterpiece one hundred million years in the making. It meanders 60 kilometers amid karst rock peaks that rose eons past, eroded into winding valleys formed by the aqua-colored stream that cuts through China’s oolong tea capital – Mount Wuyi in the north-east part of the Fujian Province. Mount Wuyi’s most famous oolong teas are Big Red Robe, Iron Apostle, Golden Water Turtle and White Rooster. Listed in 1999 as a UNESCO world heritage site, Mount Wuyi is rich in cultural history, biodiversity and breathtaking scenery. It is an area where Buddhism, Taoism and Neo-Confucianism met and intertwined, which attracted scholars and spiritual seekers from all over Asia.

Staying true to Chinese linguistic form, the Nine Bend River was christened with a literal name. In a country where computers are called electric brains, contact lenses are called invisible glasses and chameleons are called color-changing dragons, it figures that a river with nine bends in it would be called Nine Bend River.

The river inspired one of China’s most celebrated neo-Confucianism scholars, Zhu Xi (1130-1200), also known as The Tea Immortal, to write the poem of ‘The Boat Song of Wuyi’s Nine Bends’. The poem is divided into nine parts – each part eulogizing the unique landscape around each bend. Over the centuries, the poem has sparked much debate in Chinese and Korean academic circles as to whether the work is simply a poetic description of the landscape or is a philosophical lesson in metaphoric form.

Taking inspiration from Zhu Xi’s poem, I too will share with you the sights to behold around each bend.

The Ninth Bend

On a warm and humid Mount Wuyi spring day, stepping onto the bamboo raft brings the welcoming sensation of cool water running over my feet. As I recline into the bamboo-thatched chair, one of the first things I notice are flashes of silver darting beside me in the water. The water is so clear that I can see the schools of fish gathering around us in anticipation of the fish food the children brought onto the raft.

If you rafted China’s other famous karst mountains in Yangshuo in the Guangxi Province, the start of the Mount Wuyi trip may seem anti-climactic. The Nine Bend River prefers a slow build-up rather than playing its best cards upfront.

The Eighth Bend

Around the eighth bend, increasingly larger black boulders rise above the water, peppered with lush greenery. Some trees seemingly grow in defiance of the laws of gravity as they peek out of vertical crevices. From this bend onwards, the pole-man points out rock formations that have been dubbed with imaginative names, such as the Water Turtle Rock and the Sydney Opera House Rock. Rock shapes are much like cloud shapes – they’re in the eye of the beholder.

The Seventh Bend

Around the seventh bend, I start to notice tea gardens tucked away behind the riverside foliage. Against the foreground of the crystal-clear water, I am reminded of how water was both an important factor in the shaping of the Mount Wuyi landscape and a vital contributor to a superior pot of tea.

The Sixth Bend

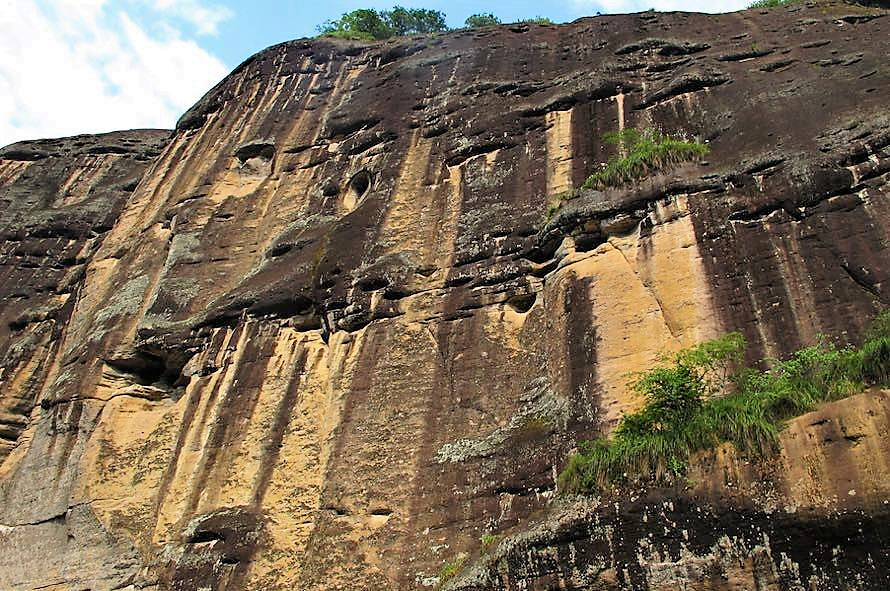

Around the sixth bend, the river plays one of its ace cards. A massive ninety-degree angle cliff, christened ‘The Immortal’s Palm’, dramatically soars up sky- high. Standing at 400 meters high and 200 meters wide, thousands of years of downward flowing water have carved out long, vertical ridges along the face. It is the grandest rock I’ve ever seen.

At this bend you can also see Chinese script carved into the rock-side by Zhu Xi himself – “Time flows like water”.

The Fifth Bend

The river widens and shallows out at the fifth bend, with larger fish to be seen. It’s tempting to throw in a line, but I’m reminded by our pole-man that the reason for the abundance and diversity of fish in the river is due to a ban on fishing and forestry operations since the 8th century.

The Fourth Bend

Around the fourth bend, there’s more stunning rock features to be seen. Our pole-man explains to us how the region is part of the Cathaysian fold system that experienced high volcanic activity and the formation of large fault structures, which were subsequently eroded by water and weathering to form the columnar and dome-shapped cliffs and cave systems. The peaks on the western side of the Wuyi Mountains are mainly volcanic and plutonic rocks, whereas the peaks on the eastern side are mainly red sandstone.

The Third Bend

The most fascinating bend is the third one. Zhu Xi wrote in his poem:

“In the third bend you will see the boats inserted into crevices. No one knows how many years have passed since the rowing ceased.”

Zhu Xi is referring to coffins that are up to 3,800 years old hidden away in cavities on a cliff-face. The tombs belonged to the ancient Min-Yue ethnic group. The coffins resemble the shape of a boat and some even have oars. Legend has it that the coffins would be used as boats by the gods to bring the souls of the dead to paradise. In 1979, anthropologists excavated a coffin, measuring 4.89 meters long and carved out of a complete tree trunk. Inside the coffin was an intact skeleton over 3,400 years old.

The Second Bend

Around the second bend is the iconic symbol of Mount Wuyi – The Jade Maiden Peak. A tall, slender and smooth rock of unusual shape. The legend goes that the Jade Maiden came down from heaven to admire the beauty of Mount Wuyi. She met a mortal – The Great King – and they fell in love. A jealous monk, named Iron Slab, snitched to the Heavenly God who, in turn, punished all three by turning them into stone. Today, Iron Slab Peak – also nicknamed The Home Wrecker – stands between The Great King and Jade Maiden Peaks, forming a rocky love triangle.

The First Bend

Around the first bend, a rock face with calligraphy and poems carved into it comes into view, and soon after, the river flattens into a delta, marking the end of the rafting trip.

Getting off the raft, I’m filled with a sense of wonder, serenity and gratitude. Floating down the Nine Bend River was one of the most beautiful experiences of my life. I’ll be back many times, but next time I’ll take a flask of tea to get more into the spirit of the place.

I completed the day with a visit to the nearby Wuyi Palace (an ancient Taoist temple built in 742AD) and a bonsai garden that no doubt rivals some of Japan’s best.

Practical Advice

Rafting Tickets

It is generally not easy to get tickets for the rafting trip on a weekend, so either book in advance through an agent or go on a weekday. If there have been rainstorms, the rafting trips will be cancelled.

Guided Tours

If you would like your pole-man to explain the features and history of the river to you, it costs around US$4 per person. If you don’t speak Chinese, then you can pay for a local tour guide to accompany you, which should cost roughly US$30 for the entire rafting trip. But be careful when choosing a tour guide. Some are lazy and will falsely claim that the river has no historical significance to get out of doing their job.

Buses

If you decide to travel on your own, buses 6 and 9 will take you to Star Village (the last stop), where the rafting trip starts.

Tasting Notes –

Wuyi Star Tea House

At the end of the rafting trip, go up the rock steps to the left and you will find a tea house owned by Mount Wuyi’s biggest tea company – Wuyi Star. You can book a tea ceremony and taste some of the best Wuyi rock teas. A one-hour ceremony costs around $15 for a group of 5 people, plus the price of your selected teas. One of their most interesting teas is Yellow Goddess of Mercy (Huang Guan Yin). It is a hybrid of Iron Goddess of Mercy (Tie Guan Yin) and Yellow Dawn (Huang Dan).

Tea Market

Get More Value from Your Tea: BRU Maker One

+41794574278

Jacque's Organics

(647) 804-7263

Hi Jaq:

It might be useful to readers to explain that karst is limestone, easily etched by water, especially if acid is present, such as from decaying vegetation or acid rain.

The Jade Maiden Peak looks to me like a basalt pluton, not karst. Such rock towers, like Devil’s Postpile in the US, are much harder than karst limestone, so they tend to remain after everything else has been eroded away. The “posts” tend to look hexagonal because of the way basalt cools and crystalizes.

Bill, tea lover

Hi Bill. Thanks for your comment. I’ve scoured the internet in both English and Chinese, but unfortunately haven’t been able to find a source explaining the composition of the peak. So I’ve simply deleted the word ‘karst’.

Hi Bill,

I read the introduction of Mt. Wuyi in Baidu in simplified Chinese, and found that the scenery along the nine bend river is actually not karst landscape, but they do have some karst scenery nearby.