Where does tea flavor come from? The word “terroir” translates from the French to “of the earth.” It has become a fuzzy colloquial expression served up as a catchword that tries to resolve a mystery simply by naming it. The concept has been long in the making, dating to the very earliest Latin writings on wines. It’s a dominant theme across the Medieval and early centuries that shaped the French sense of identity. And its focus has moved from wines to fruit, cheese, and tea.

The concept of full spectrum terroir has evolved from a description of a place, the soil, the terrain, and the setting to include a larger scope of flavor influences that acknowledge the importance of post-farm processing techniques. As Mark Matthews writes with intentional understatement in Terroir and Other Myths of Wine Growing, “No doubt what happens in the vineyard is important, although one might suspect that some of what happens in the winery is important also.”

Kevin Gascoyne, in Tea, History, Terroir, Varieties, also supports this more inclusive concept of terroir, “Just as the cultivation of the tea tree has a long tradition in China, the processing of the leaves is an art that the Chinese mastered many centuries ago. Chinese tea production is based on the agricultural traditions of each region, and so different methods of processing have been adopted by each region.”

Where are the start and endpoints of terroir? In many cases, it is impossible to separate the influences of the fruit of the fields from the fruits of labor, and where those boundaries have been set has been as much arbitrary as it is contrived. Is the harvest the endpoint of the influence of terroir? Or do we allow that the harvesting method itself, when the fruit is first separated from its source, makes its impact and accept that harvesting by machines will produce an altered final product from that gathered by hand?

Looking more broadly, does the distance that the harvested product must travel (and be preserved) before it arrives at its processing point play a factor? Even before we get to the actual processing of the harvested product we’ve identified important milestones that will affect the result. Terroir is more than just the physical space occupied by the land; it’s how fields and labor come together to answer the core question: where does the flavor – of a tea or a wine – come from?

This article examines the concept of terroir as an answer evolving over time, looking at its historical, political, and philosophical perspectives from the East and the West. At the end I’ll present a model for the concept in the hopes it will provide a useful construct for framing an all-encompassing set of parameters.

Romans first describe terroir

Early Romans enjoyed a rich variety of wines, ranging from the many regions in what eventually became Italy, Greece, and Europe. Among the earliest wines regaled by their place of origin were those of Armenia, glowingly described by Virgil and Pliny, two writers who had a pervasive influence on poets and historians through the next fifteen hundred years. The area enjoyed a long heritage of farming and shipping; the 2007 excavations of the Armenian ‘Areni-1’ caves revealed a neolithic winery dating back to 4100 BCE.

A surprisingly early reference that parallels our concept of terroir comes from the 1st century CE. In De Architectura, the Roman writer and engineer Vitruvius asserts the importance of native regional influences; “… If the roots, as with vines… did not take on qualities according to the virtue of territories, and the fruits did not take on fragrances in the same way, the flavors of everything would in each country be the same… ”

Out of the Darkness: France adopts Bacchus

Bacchus of ancient Rome embodied wine culture – or at least wine partying. He is often portrayed as a languorous, androgynous male, appearing with heavily burdened grape vines, a wine goblet, and various nymphs and satyrs. This son of Zeus was the God of the grape, the harvest, of wine, ritual ecstasy, and fertility. The original party animal but with the ‘edge’ of a God, his many exploits include drinking his older brother Hercules under the table. The Roman poet Virgil adapted the essence of Bacchus in his Georgics (29 BCE), which included detailed information on viticulture. Virgil’s Bacchus is less the ‘wild child’ deity from ancient Greece (Dionysus), but has instead been imbued with a greater sense of purpose, a “carpe diem” resolve (progenitor to the very French concept of ‘joie de vivre’), and is clearly linked to the earth, is of the earth, and especially to wine.

France emerged from turbulence. Prior to its consolidation and flourishing around the 14th century, it had endured continued conflicts with Gallic, Roman and Viking armies and waves of German tribes. Wars among the great families and kingdoms made famine and brutal poverty the norm for most of its population. The brief Black Plague of 1347-53 killed over half of Europe’s population and perhaps 80% of that of France. It was followed by the Hundred Years’ War with England, whose soldiers infamously relied on ‘scorched earth’ pillage to roam and destroy. Finally, under the leadership of Charles VII and his brilliant warrior saint Jeanne d’Arc, the English were expelled, and the nation of France began to coalesce.

This period saw a long sustained warming cycle which fueled what became a proud tradition of farming and food. Agriculture was part of a new perspective on land, renewal, and prosperity. Its leaders, writers, painters, and chroniclers very consciously started with a look back to classical antiquity’s Virgil; all France needed was a unifying spark. Viticulture was a salient part of this, and the now more peaceful ebb in European culture set the stage for the development of the West’s concept of terroir. Papal recognition of the importance of quality wines was already well established; the poem Battle of the Wines, written by Henry d’Andeli in 1224, describes a wine tasting competition hosted by French king Philip Augustus. Over seventy wines from all over Europe were sampled and rated by an English Priest as either “Celebrated” or “Excommunicated,” thus putting the official imprimatur on the notion that wines from some regions are superior to those of others.

During the Renaissance, the kernel of French identity was born (in part) out of reframing the glories of the past. The group of French poets later called the ‘Pléiade’ began a re-characterization of Virgil’s Bacchus. As Thomas Parker writes in Tasting French Terroir, “The agricultural metaphor from Virgil attests to a practice and a nationalistic set of aesthetics that would apply to both language and the vine, reinforcing agricultural standards through linguistic ideals.”

Within five years, three books were published in France via Gutenberg’s new communications grenade, the printing press, that would titrate the concept of terroir – as well as a French self-awareness and identity.

In 1549, the Pléiade writer Joachim du Bellay’s Défense et illustration de la langue française (“Defense and illustration of the French language”) took pains to link the French countrymen with a character and quality that was characteristic of the French countryside. That same year, Jacques Gohory’s Dissertation on the Vine, Wine, and the Harvest was the first technical book to be written in the French language. He updates, advances, and defines the agricultural science and linguistic legitimacy of French methods and instruction.

Five years later in 1549, French physician Charles Estienne, published L’Agriculture et la Maison Rustique (“Agricultural farming and the Country Home”). He emphasized the links between wine, its region of origin, and its regional populace and made a forceful case that all three are fused in the crucible of locale. He also directs that one should be drinking only the wines from one’s own region, because wine and its local consumers are both the result of the same regional affinities.

From Thomas Parker; “To put it simply, the poets of the Pléiade shaped the French imagination of regional wine culture by using vines as a metaphor for language production.”

From wine to tea

If one could distill the identity of an entire country down into a single beverage, one that represents the spirit, ideology, and experience of a nation of peoples, for France that drink would certainly be wine. There is such an equivalent elixir that represents the untold generations of China: tea.

In wine’s 800-year relationship with France, it entered the national psyche and emerged to enable, then embody, the spirit of a people. In China, by contrast, tea has accompanied the individual since prehistory in a personalized symbiosis that fostered individual creativity and meaningful introspection. While there are plants with an older pedigree than tea (such as oats and wheat), perhaps none better exemplifies the ‘co-evolution’ between Man and Plant, as described in Michael Pollan’s book The Botany of Desire. From the source material of only one plant, the evergreen tree Camellia sinensis, mankind has fashioned uncounted thousands of different types of tea.

The foundations of culture in China are inextricably linked with tea, and the Emperors who strolled out of prehistory and into legend were Gods themselves. The progenitor of China’s tea knowledge and ideology was Shên Nung, the “Divine Farmer” from the 27th century BC, and mythic founder of Agriculture and Chinese herbal medicine.

The notion of terroir was embodied early in Chinese beliefs as a spiritual representation of place, engendered by local water gods, river gods, mountain gods, etc. The natural world was the world, populated and governed by gods, and while mankind could influence, he could not escape or override their predominance. In the Chinese Art of Tea John Bloefeld writes, “Whereas the Chinese educated classes have always tended to be agnostic and therefore doubtful about the propriety of having much to do with supernatural powers, their abiding love for nature in its untamed aspects is a reflection of deep spiritual feeling, for their fundamental tenant, has always been a conviction that life itself, flowing in accordance with mysterious natural laws that operate in sweeping cycles of change, is charged with spiritual significance.”

Man’s relationship with Nature

The western approach to the world has been typically linear and dependent upon observable boundaries; a quantitative quid pro quo, a cause-and-effect viewpoint that positions man as an observer, not the participant. In the example from the early Renaissance, the concept of terroir was man’s attempt to define the universe by putting a label on it, followed shortly by the flag of regionalism. “Terroir” was the culturally-infused shorthand to resolve the mystery of why wine can taste markedly different from one valley to the next.

Here grows the clear distinction between the existential paradigms of East and West. In tea, China’s closest equivalent of terroir concluded that man is of the natural world, and no distinction between man and any other element of the world around him made any sense. As Bloefeld explains: “Certainly, Taoist recluses and Buddhist monks played an important part in the development of tea…, but it is doubtful if they ever attached to it a profound spiritual significance other than that which they believed to be inherent in every aspect of life.”

The result of this acceptance is the simple recognition that, while there are certainly localized differences across China, the characteristics distinct to a region (defined by province or even hillside) are accepted as the natural result of all that is there. The tea that embodies the qualities which mark the Wu Yi mountains of Fujian for example is distinct precisely because it was grown in that region and harvested and processed by tried and true methods that reflect a proud and comforting legacy for the Chinese people involved in its manufacture, as well as its consumption. All is as it should be – naturally.

Today, we know much more about the variables that contribute to the concept of terroir. We name the soil micronutrients and identify its micro-ecosystems. We can evaluate that patient solvent, Water, with its own contributing regional qualities. We have experimented with varietals and clones, grafted new strains onto old mother root stocks, blended the variables to predictable consistencies, but – with all our knowing, have generally edged further away from understanding and appreciating.

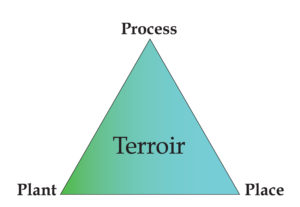

Today, the concept of terroir is still in flux, though trending toward a more widely accepted framework for an all-encompassing set of synergistic influences. To model the example of tea, we can employ a triumvirate of broad variables under the headings of Plant, Place, and Process.

Plant

By most accounts mankind first encountered the tea plant in the regions that lie on either side of the Mekong River basin, in countries known today as China, Myanmar, Laos, Vietnam, Thailand, and Cambodia, and is represented by three main varietals, Camellia sinensis, var. sinensis, C. sinensis, var. assamica, and C. sinensis, var. irrawadiensis. All other attributes of the leaf, (e.g., clones or grafting techniques,) fall under another of the three headings, that of Process.

Place

‘Place’ comprises the variables which are inherent to the locale of the growing plant; all geographic conditions such as elevation, weather, sun duration and orientation, wind patterns, natural mineral content of soil and water, etc. Here too, are the contributions of ecosystem; the plants and animals (non-human) which are part of the environment, and how dynamic it is; terroir can change with the seasons.

Process

This is the most complex set of variables, defined as any that are the result of the hand of humans. This includes:

- All created clones and cultivars,

- Growing and harvesting techniques (e.g., manual or mechanical),

- The finished tea attributes introduced by the processing of the harvested leaf, thus producing the six main types of tea: white, green, yellow, oolong, black, and puers,

- Transport and storage methods of the resulting tea,

- The styles of preparation and drinking (consider Gong Fu style preparation vs. “Grandpa style” tea drinking).

Terroir is the result of the combination of an ever-changing set of dynamics, and it is also a simplified conceptual expression that stands for those variables which define the qualities of any tea; it represents both cause and effect. These three sets of variables; plant, place, and process, combine synergistically to create a whole that is greater than the sum of the parts: terroir.

Lou Berkley writes about tea, history, and science. He lives in San Francisco.

Bibliography

Mark A. Matthews, Terroir and Other Myths of Wine Growing, 2015, pg. 146

Kevin Gascoyne, et. al., Tea, History, Terroir, Varieties. 2011, pg. 56 (italics mine)

Thomas Parker, Tasting French Terroir, 2016, pg 28, 29 (italics mine)

Vitruvius, De Archetectura, Book VIII, Chapter III, paragraph 12 (Loeb edition numbering), 1911

Philip Daileader; The Late Middle Ages, The Great Courses (DVD course), 2007

Michael Pollan, The Botany of Desire, 2001

John Bloefeld, The Chinese Art of Tea, 1997, pg. 103 (italics mine)

Tea Market

Get More Value from Your Tea: BRU Maker One

+41794574278

Jacque's Organics

(647) 804-7263