Tea offers adventures unlike those of any other beverage. Some take their search for tea across the globe. For others, the adventure is more local, such as the discovery of a new teahouse to sample teas. We can all invoke our own special and intimate adventure in our senses and minds as we sip our cup.

Tea offers adventures unlike those of any other beverage. Some take their search for tea across the globe. For others, the adventure is more local, such as the discovery of a new teahouse to sample teas. We can all invoke our own special and intimate adventure in our senses and minds as we sip our cup.

The first step begins with our eyes. We anticipate the adventure as we look into the cup, even before the tea’s aroma wafts to our nose. Whether we are aware of it or not, the sight of the golden brown of a Darjeeling already evokes warmth in our nose and brain. The bright green of matcha immediately translates into the expectation of a refreshing coolness.[i] The pale yellow of green teas teases us. Have you ever felt, as you pour green tea in a white cup, a faint sense of mystery, of not quite knowing what flavor to expect? The tea’s pale color gives your brain no clues about the experience to come.

As you sample your tea, close your eyes, the better to focus on the actual experience. As you bring your cup to your lips, you breathe in the tea’s aroma. Cells in the anterior olfactory patch at the roof of your nose use their receptors to latch onto specific odor compounds that emanate from the tea. Receptors are protein molecules embedded in the cell membrane. They notify the cell of the compounds they captured. Every odor activates many different olfactory bulb cells.

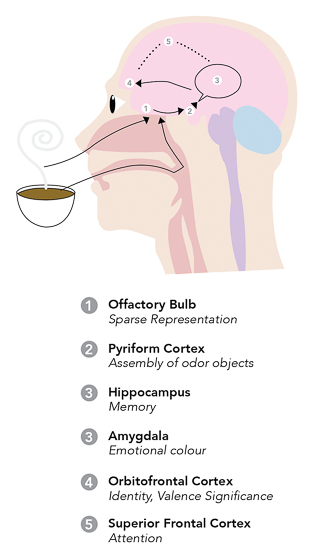

Each of the cells sends a signal to the bulb (label 1 in the figure). There, the signals from all the activated cells are assembled into a “sparse representation.”[ii] The sparseness comes from the bulb’s capacity to ignore signals from our usual ambient odors and only send on those from “new” ones.

The “new odor” signals make their way to the piriform cortex (2), where they are put together into “odor objects.”[iii] You don’t perceive the individual compounds when you smell a mixture. Instead your brain assembles the signals from the tea’s multitude of compounds into at most four smells that you can identify individually. Indeed, we humans cannot identify more than four separate compounds in a mixture, and, under most circumstances, far fewer—it takes practice and focus to identify four, or even three. So, don’t feel badly if you can’t identify the different aromas people may claim they experience in a wine or a tea. Indeed, the more sensitive you

The “new odor” signals make their way to the piriform cortex (2), where they are put together into “odor objects.”[iii] You don’t perceive the individual compounds when you smell a mixture. Instead your brain assembles the signals from the tea’s multitude of compounds into at most four smells that you can identify individually. Indeed, we humans cannot identify more than four separate compounds in a mixture, and, under most circumstances, far fewer—it takes practice and focus to identify four, or even three. So, don’t feel badly if you can’t identify the different aromas people may claim they experience in a wine or a tea. Indeed, the more sensitive you

are to aromas in general, the fewer you will be able to identify individually.

Sip and swallow your tea. A panoply of aroma chemicals enters your nose, this time through the back of your throat, reaching the posterior portion of the olfactory bulb. There, a fresh sparse representation develops, which may be different from the one that you experienced when simply sniffing the tea.

For example, one of the most intriguing features of tea is that the orthonasal experience of a tea’s floral qualities may be more intense than the retronasal experience. The brain seems to differentiate between odors from foods and those from flowers: flower aromas are muted when experienced retronasally.[iv] I have wondered whether this difference in intensity contributes to some people’s disappointment when sipping highly floral teas—the tea’s flavor intensity does not match the intensity of its aroma.

Once the piriform cortex has assembled the odor object(s), it passes the message on to three essential centers in the brain: the hippocampus, the amygdala, and the insula. At the hippocampus the signal elicits memories, especially place and person memories. When I sip a bai hao, I am immediately brought to the place where I first savored it: sitting with the charming but aging Dutch artist with whom I first shared the experience. Equally immediately, thanks to my amygdala, I experience both pleasure and sadness—pleasure from the aroma, and sadness because my artist friend is no longer among us. These experiences come to mind effortlessly, without conscious awareness.

The “what” requires more effort. The insula must bring together the present experience of the tea—its taste and trigeminal stimulation—with memories and emotions, so you can “place” the tea in your mind’s eye.

If you want to put a name to the tea, you must make a further effort. Flavor experiences tend to be right-brained while, for most people, vocabularies are in the left brain. Our hemispheres must communicate back and forth to establish a name for the smell. With wine experts, this naming comes during swallowing, when retronasal stimulation is at its peak![v]

This interhemispheric communication may become easier as you practice developing your vocabulary. Interestingly, wine experts, but not coffee experts, agree on a common vocabulary that is easily elicited.[vi] So far, we don’t know whether tea experts are more like wine experts or coffee experts; this question has not been explored.

For the last step in the journey, the orbitofrontal cortex of the brain, right above the eyes, comes into play (4). There, all the inputs from the other brain areas are put together to give us a conscious awareness of the nature of the tea, its valence (good, bad, or something in-between), and its significance: is sipping this tea important to me or should I ignore the aromas emanating from it as I read my engrossing book?

Which brings us to 5 in the figure. This is a side trip on this journey, one characteristic of oolong teas and puers. It is created by the presence of unexpected aromas, such as that of indole in the case of oolongs. The aroma of indole is simultaneously pleasant and unpleasant. This ambiguity “confuses” the amygdala—what message should it send on to the orbitofrontal cortex for final analysis?

The amygdala notifies the superior frontal cortex of the confusion, which in turn wakes up the orbitofrontal cortex, saying in essence: pay attention, you must decide here about which path to take! Do you continue sipping or do you reject the tea? You may have felt this increase in focus when sipping an oolong—I certainly have!

The journey you take each day as you sip your tea is wondrous. The journey of the tea leaf from bush to cup is also the intimate journey from cup to mind and memory, to pleasure and joy.

[i] Michael, G.A. et al., 2010. Hot Colors: The Nature and Specificity of Color-Induced Nasal Thermal Sensations. Behavioural Brain Research 207, 418.

[ii] Thomas-Danguin, T. et al., 2014. The Perception of Odor Objects in Everyday Life: A Review of the Processing of Odor Mixtures. Front. Psychol. 5, 504.

[iii] Thomas-Danguin T. et al. Ibid.

[iv] Small, D.M. et al. 2005. Differential Neural Responses Evoked by Orthonasal versus Retronasal Odorant Perception in Humans. Neuron 47, 593.

[v] Pazart, L. et al., 2014. An fMRI Study on the Influence of Sommeliers’ Expertise on the Integration of Flavor. Front Behav Neurosci. 8, 358.

[vi]Croijmans, I., Majid, A., 2016. Not All Flavor Expertise Is Equal: The Language of Wine and Coffee Experts. PLoS One 11(6), e0155845.

Tea Market

Get More Value from Your Tea: BRU Maker One

+41794574278

Jacque's Organics

(647) 804-7263