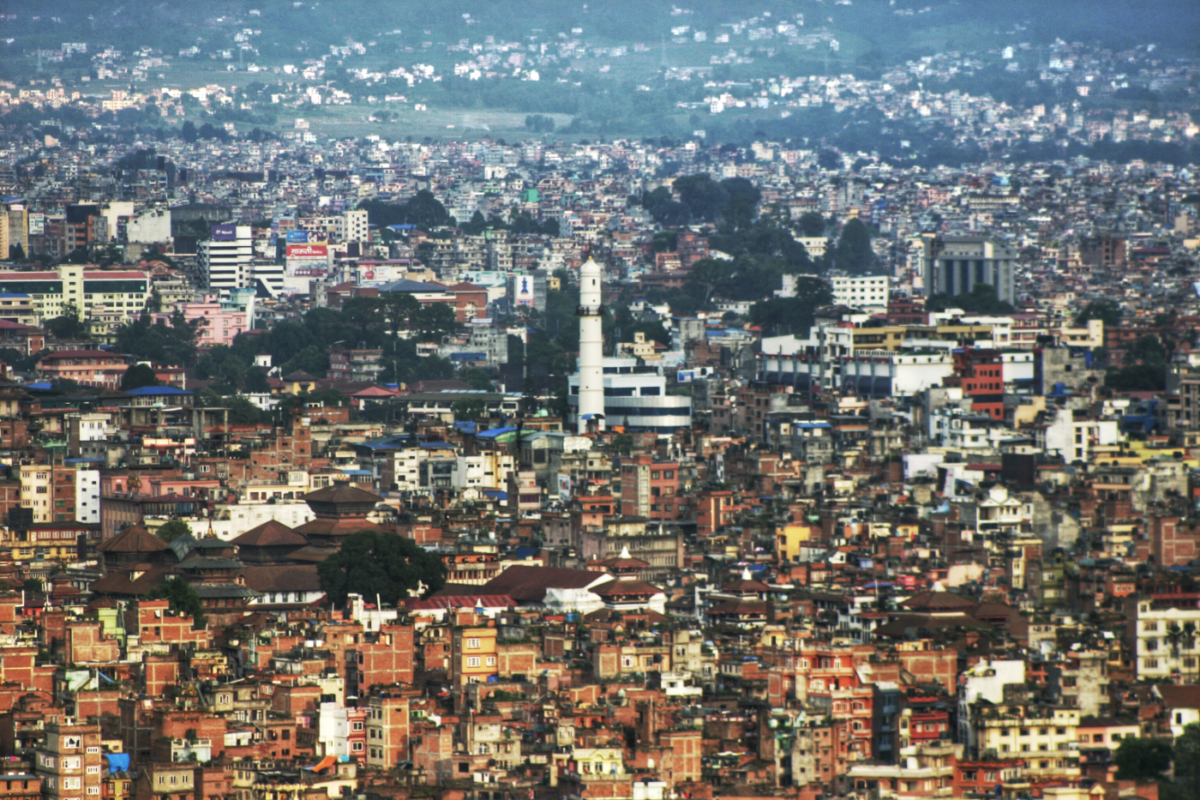

Bekha Narayan Dangol (right) and Jog Narayan Dangol at the counter of their tea shop Tilauri Mailako Chiya Pasal near Dharahara tower in Kathmandu. The Dangols started selling tea in the 1940s, operating one of Kathmandu’s first and most famous tea shops. Photo courtesy: Rinendra Man Singh

Two Tea Shops and a Peek into Kathmandu’s Tea History

By Prawash Gautam

“Tea?” Bhairab Risal looked somewhat astounded when I asked why his family didn’t drink tea. “Where’d you get tea those days?”

Risal is known for his extraordinary life as a veteran journalist with a sharp memory at 94. He spoke with ease and zeal of his first tea experience and the early days of Kathmandu’s tea culture.

“We drank milk in the morning,” he said. “But in those days, it was common for smokers to start their day with a hookah, or for Newars with a little home-brewed alcohol.”

In 1948, at the age of 20, Risal drank his first cup of tea at one of Kathmandu’s earliest tea shops, Tilauri Mailako Pasal.

“Tea shops were just beginning to open, and you could count them on your fingers,” he said. Echoing Kathmandu’s elderly population, he recalled that Laptanko Hotel was another well-known tea shop in Kathmandu in the 1940s and 1950s.

Their stories, weaved from scarce snippets of information drawn from the elderly like Risal and secondary sources, are inadequate to paint a complete picture. Yet, they provide us with a valuable peek into Kathmandu’s early tea shops and tea culture.

Soldiers return, and tea shops are born.

Before the first tea shops opened, only a few of Kathmandu’s elites and the privileged class drank tea.

Historical accounts indicate that Kathmandu’s rulers, Shahs and Ranas, first encountered tea after opening to British residency in Kathmandu in 1816. Ranas’ link to tea in the 1800s is also evident from the gift of a tea sapling from the Chinese emperor to Prime Minister Jung Bahadur Rana. Rana’s son-in-law Gajaraj Singh Thapa, in 1863, planted the sapling in Illam in east Nepal, establishing the country’s first tea garden.

Nepal’s merchant class, including the Lhasa Newar traders, had a long history of tea drinking due to their travels to Tibet. Beginning in the seventh century, Newar expatriates acted as a bridge for economic and cultural exchanges along the Silk Road with ties to India’s Bengal cities, including Calcutta (modern Kolkata). The Buddhist Kingdom of Lo, called The Forbidden Kingdom, annexed by Nepal, retains close ties to Tibet.

Nepal, the oldest sovereign state in South Asia, does not share the colonial history of neighboring India. Commoners were restricted from trading in global markets for goods like tea. The World Wars changed this, as 40 battalions totaling more than 112,000 Nepalese enlisted to fight alongside the British on the battlefields of Europe and Asia.

These soldiers returned with the customs and food habits of the West, including tea. As a result, Kathmandu’s elderly residents commonly attribute the Valley’s tea culture to these returning soldiers.

Tilauri Mailako Pasal borders the expansive Tundikhel grounds, 300 meters wide and five kilometers long, where the Nepal army soldiers paraded every evening.

“Like most early tea shops, Tilauri Mailako Pasal was also a sweet shop that sold traditional sweets like nimkin and tilauri and existed before 1934. It also started selling snacks like aloo chop and beaten rice when it relocated to a place near Dharahara,” said 64-year-old Bidhya Man Singh, son of Jog Narayan Dangol, who owned the shop along with his brother Bekha Narayan Dangol.

“Soldiers were regular customers at the shop and stopped after evening parades for snacks and conversations,” said Rinendra Man Singh, the 78-year-old son of Bekha Narayan. “They started asking for tea. That’s how my father and uncle started selling tea.”

The shop was selling tea by 1945 at the latest, as recounted by Jog Narayan in Right Living, a book by YB Shrestha Malla.

Rinendra and Bidhya Man said the tea shop operated out of a small ground-floor room. It was a crowded space, with a counter on one side and a few benches on the other.

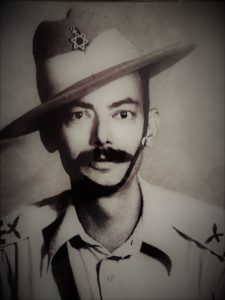

The tea shop had fascinated Kathmandu residents for several years when another tea shop opened in the Kathmandu suburb of Dillibazar around 1948. Owned by a retired second lieutenant of the Nepal Army, Krishna Bahadur Khatri Chhetri, it became famous as the Laptanko Hotel (laptan is the Nepali word for lieutenant).

In his essay ‘Dillibazarko Laptanko hotel’ [Laptan’s hotel in Dillibazar], author Arbind Rimal describes the tea shop as being on “the ground floor of a simple-looking house with a tiled roof.” Chhetri had stuffed a few tables and chairs in the small room. In one corner, he placed a stove where he prepared a small menu of potato curry, chickpeas, beaten rice, biscuits, and tea.

From their mundane, cramped spaces, these tea shops appealed to the broader imaginations of Kathmandu citizens by introducing them to a novel drink from faraway lands.

Tea from faraway lands

Nepal was first introduced to specialty teas, including green tea and oolong, owing to influence from China. However, British rule in India meant that the interactions with the British ultimately shaped Nepal’s tea habit. Nepal had a population of only six million in 1940, with fewer than 100,000 living in the valley of Kathamandu, mainly Newars.

By the time the first tea shops opened, the tiny proportion of Kathmandu residents that consumed tea were already drinking black tea, mostly prepared the India-style – tea leaves and water boiled together with milk and sugar. It was not until the 1960s that CTC (cut, tear, curl) tea – referring to the processing method of black tea, became widespread. CTC remains the most common processed tea in Nepal. In the 1940s, tea bags had yet to be introduced.

Anecdotal evidence suggests that Kathmandu imported famous British tea brands such as Brooke Bond and Lipton Yellow Label, a tea manufactured as far away as Sri Lanka in those years. However, most tea supplies came from the Indian cities of Kolkata, Darjeeling, and Benaras. Therefore, the two tea shops likely got their supplies from these places.

A compounder named R P Sitly imported tea for the Tilauri Mailako Pasal. “I imported tea from Darjeeling, the best tea than being Lepcha tea,” he recounts in the Right Living. He further writes, “Most of it [the tea], I managed to sell through [Jog Narayan] …who had a small tea shop.”

The tea shops prepared tea in the Indian style. Tilauri Mailako Pasal was mainly known for its unique way of preparing sweet milk tea.

“They prepared black tea and milk separately. Then, they only mixed them proportionally in a tumbler and added sugar before serving,” said Bidhya Man.

Both shops served tea in glass tumblers and sold a full and a half glass of tea.

Arresting Kathmandu’s imagination

The colored, sweet drink instantly astonished customers.

Growing up, Bidhya Man listened to his father share many instances of customers’ fascination with tea. many stuck with him.

“Many early customers were awed at why they were only provided the sweet drink while separating the solid tea leaves,” he said. “‘Why do you only serve us the soup? Don’t you plan to serve as the fleshy portion as well?’ they’d tell my father. Some said in earnest, while others in jest.

“They were also fascinated by the method of drinking tea. They were visibly amused that they were introduced to a drink from the foreign countries.”

Rizal’s early tea experience tells of such fascination with tea among early customers.

“Sipping hot tea was delightful,” he writes in his memoir Sushila-Bhairab. “My mouth would burn while drinking the hot tea. My tongue was not yet accustomed to the way of drinking tea. I would take the glass and sip the tea by cooling it with my breath and making a slurping sound. I’d be tired of my tongue burning.”

Change and dissent at early tea shops

Alongside fascination, these tea shops pervaded the spirit of freedom. In the 1940s, Nepal was at the height of a revolution against the autocratic Rana regime.

“Tea was referred to as kangreshi or the habit of the dissents or outcasts, after the banned Nepali Congress party,” he said.

In his essay, he wrote, “At that time, the conscious citizens believed drinking tea outside of the home to be an expression of their free expression and behavior.”

As a result, tea shops became sites where people gathered to discuss politics ̶̶ surveillance by the secret police soon followed. The Laptanko Hotel was widely known as a political and intellectual hub.

“Both before and after democracy, Laptanko Hotel was like a hub to drink tea for the conscious [people],” wrote dramatist Shyamdas Vaishnav in the foreword of Rimal’s essay collection. “Especially, politically conscious middle-class youths had energized this place along with its tea.”

Tilauri Mailako Pasal was also a meeting point for students and politically conscious youths. Various accounts reveal that BP Koirala, the noted underground leader of the Nepali Congress party leading the revolt, disguised himself as a priest to visit the tea shop. These accounts state that during long hours he sat there, sipping quietly and listening to other customers talk.

Tea shops rise post-democracy

In 1951, the revolution succeeded, and democracy dawned in Nepal. Risal, who lived through these momentous changes, saw the number of tea shops surge in the post-1951 period.

“Tea shops really spread tea culture in Kathmandu,” he said. “Slowly, people started having it in their homes. In villages around Kathmandu city, people started having tea at their home only in the 1960s.”

And what happened to these two early tea shops?

Laptanko Hotel closed in the late 1960s and Tilauri Mailako Pasal in 1979.

“They remain in my generation’s memories as tea shops that introduced and taught Kathmandu how to drink tea,” said Risal.

Tea Market

Get More Value from Your Tea: BRU Maker One

+41794574278

Jacque's Organics

(647) 804-7263

What a fascinating account.

Enjoyed the read.

Thank you.

Wonderful story. I hope to visit someday.

Enjoyed the story. Now, looking forward to a story on tearooms for trekkers 🙂