“Sometimes as you stare into the porcelain you lose yourself, immersed in a kind of surreal beauty,” says Chenglong Lu, research fellow at the Forbidden City Museum in Beijing and a standing committee member of the Ancient Pottery and Porcelain Study Council of China.

These bowls do not appear to be the work of man, he marvels. “Rather it is work from the Creator, rendering it unique and non-duplicable, mysterious, sacred, transcendent,” he said. “Even the greatest master craftsman has no way of knowing if a masterpiece will emerge from the upcoming batch.” says Lu.

Lu is describing stoneware from Jianyao kiln, an ancient royal kiln famous during China’s Song Dynasty and crowned as one of the National Intangible Cultural Heritages.

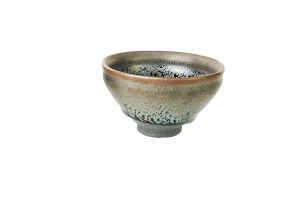

Jianware (Jianzhan) is known for firing pots with high iron content mined near Shuiji in Jianyang City, close to Wuyishan. Iron content can be as high as 7-9% — enough for a magnet to stick to the bowl.

Three precious glaze patterns

In the kiln changes occur at very high temperatures (1,300°C) during the firing process. The pottery emerges in various glaze patterns that change color. These distinctive patterns are known as Hare’s Fur, Oil Spot, Dark Gold, Tea Leaf and Persimmon Red.

The diameters of Jianware tea bowls range from 11 to 15cm, including a 13.5cm standard size for cupping and tea evaluation. Jianware can be roughly classified into three types according to its glaze patterns: Yohen Tenmoku (Yao Bian), Oil Spot (You Di) and Hare’s Fur (Tu Hao).

Yao Bian describes the intricate and variable glaze of Yohen Tenmoku. You Di (also known as Zhe Gu Ban) is a pattern named after the francolin (grouse). Both are fortuitous “accidents” that occur during the firing process in the kiln, Lu explains. Anomalies bubble and flow across the surface of the glaze throughout the firing process but these are “a gift from God,” he said.

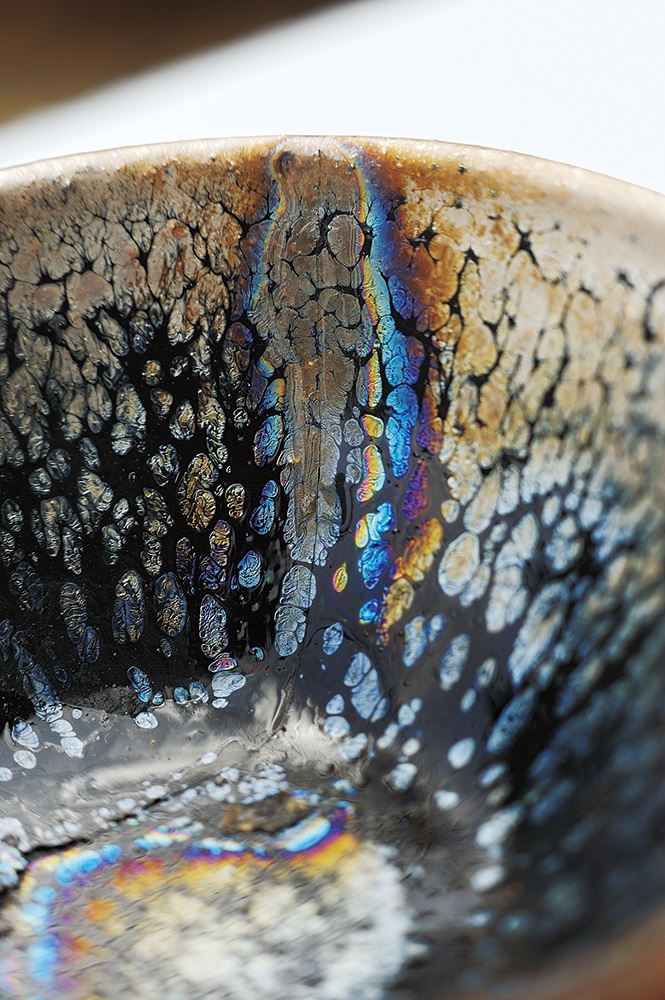

Yohen Tenmoku (Yao Bian) bowl. Top, Front, Bottom view. 60 times magnification Hare’s fur (Tuhao) pattern.

Yohen Tenmoku bowls reflect light from deep within the glaze. The most amazing thing is that its spots give off a spectrum of colorful reflective halos when observed under light. And what’s more, the light shifts and changes as one changes one’s angle of observation.

“I had the honor to see with my own eyes this ‘cosmos in itself’ bowl and indeed it is like the cosmos – amazing endless changes and color in such a delicate small tea bowl – you just cannot take your eyes off of it,” he said.

Original glaze ore

The glaze used particularly for Jianware can be divided into two major types: black glaze and mixed color glaze. Jianyao black glaze is a crystal glaze rich in iron. During the firing process, iron elements are reduced from the glaze according to changes in temperature and conditions in the kiln. Various desirable drip glaze patterns occur but they are difficult to control and impossible to predict.

Glaze used for traditional Jianyao is quarried in local valleys from strata known as the glaze base (You Ku). This sticky, acidic glaze is rich in iron and phosphate. Calcium is then added as a mix of ash from burned grass and wood. High density enables artisan potters to apply a thicker glaze resulting in darker colors after firing. In modern ceramic terminology, this is known as iron crystal glaze.

The ratio of ingredients used to achieve the effect is adjusted by the master. The pattern with its variations in color is caused by uneven temperature within the kiln. Different glaze formulas produce the three precious patterns.

Notably, there is inferior Jianware-like pottery on the market that is made with chemical glaze or natural glaze with additives used to achieve color and pattern effects at lower temperatures.

Traditionally, Jianware uses a single glaze to achieve the various colors and patterns, hence the saying “one color into the kiln, ten thousand colors from the kiln.” Different colors can be achieved by firing at different temperatures: 1,280°C produces a dark gold/oil drip effect; 1,330°C a dark reddish brown glaze; and 1,350°C a persimmon red.

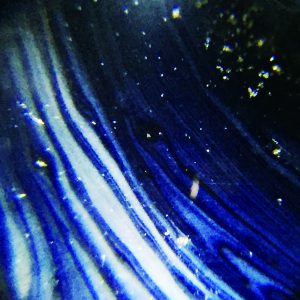

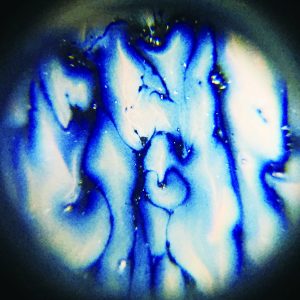

Oil Spot bowl. Top, Front, Bottom view. Typical Oil Spot pattern exhibits a cluster of tiny duckweeds which converge without merging, rendering a ripple effect. Also known as francolin (grouse) pattern.

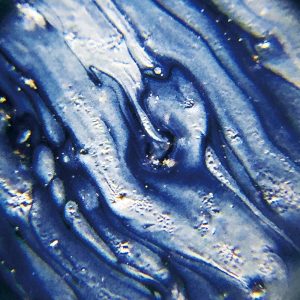

Gold Oil Spot bowl. Top, Front, Bottom view. Height: 7.8cm. Bowl diameter: 21.8cm. Base diameter: 6.8cm.

Yohen Tenmoku

Yohen Tenmoku (Yao Bian) literally translates to “changes happened in the kiln”, and describes the magnificent irregular yellowish spots against a deep black glaze of Jianware bowls. Under light, a bluish rainbow flares from the Yao Bian pattern. Colors and patterns inside these bowls change with every movement of the admirer.

During the Ming Dynasty (1368 – 1644) people believed the blood of young boys and girls contained the essence of life and that it could be condensed in porcelain, resulting in miraculous effects. There are records of human sacrifices during the superstitious ritual performed when dedicating a Jianyao kiln.

Three well-known Yohen Tenmoku bowls from this period are still revered as national treasures in Japan. The bowls are displayed at Tokyo’s Seikado Bunko Art Museum in Setagaya, the Fujita Art Museum in Osaka, and in Kyoto at the Ryuko-in of Daitoku-ji Temple. It is the most valued Yohen Tenmoku pottery in the world.

-300x186.jpg)

How are flare spots formed?

In the firing process, there is a short period when flare spots appear on the black glaze as the ferrous iron is reduced to ferric iron in a split second. The ferric iron is highly soluble and quickly dissolves into the glaze. The pattern disappears leaving a very thin membrane that forms around the spot. This creates the flare effect. If this fleeting process can be “frozen,” the flare spots pattern is achieved. In most instances the bowl will emerge with a solid black glaze. The likelihood of catching and freezing the process at the precise moment during the firing process is close to zero. This is why Yohen Tenmoku bowls are so rare and become national treasures.

Oil Spot and Hare’s Fur

Oil spots vary in diameter from 3-4 millimeters to a needle point. Some oil spots emerge golden and some silver. Iron oxide degrades elemental iron and oxygen at 1,300°C. Oxygen bubbles carrying iron ions float to the surface of the glaze in the shape of tiny duckweeds. The individual duckweeds flock together to form larger blocks displaying a ripple effect. They converge without merging.

At a slightly higher temperature, all the lines and ripples become molten again and flow with the molten glaze into long lines, creating the Hare’s fur (Tu Hao). The lines should flow from the edge of the bowl all the way down to the bottom, filling the inside of the bowl.

Tu Hao is the most commonly produced firing. There are many fewer Oil Spot bowls.

The Tu Hao pattern displays a long, thin thread flowing from the edge all the way down to the centre of the tea bowl. The pattern resembles rabbit fur.

Retold with permission from Cha Dao Life Magazine (issue 04, 2015). Chinese language Copyright 2016 Cha Dao Life . Cha Dao Life is the most reputable Mandarin tea magazine distributed within China, trekking tea stories from origins on teas, tea lands, tea brands’ social history, tea growers/processors, and teaware artisans.

Story Retold by Nan Cui

Photo credit: Qiu, courtesy of Cha Dao Life Magazine.

Tea Market

Get More Value from Your Tea: BRU Maker One

+41794574278

Jacque's Organics

(647) 804-7263

You may take a look at Jean Girel bowls …