In the households of Yixing, home of the celebrated purple clay teapots, ordinary potters are crafting something extraordinary.

Tea connoisseurs are choosy about their teaware for reasons that may not be obvious.

They differ from wine lovers who are prone to lengthy discussions about the winemaking process; dwelling on details such as the wood used in the barrels that age the wine or the distinctive shape of glassware for each varietal. Teapots are essentially the tool used to make the tea, more so than a decorative vessel to pour it. After all, dry tea is a half-finished product. The attention to teaware is justified because the pot performs such an important function.

Yixing Zisha (pronounced Yee-Shing Zee-Sha) teapots seem to be less functional at first glance, but they uniquely deserve the affection of tea connoisseurs. Yixing clay is composed of fine silt with an unusually high concentration of iron. These clays also contain mica, kaolinite and varying quantities of quartz. The percentage of clay, quartz, and iron in Zisha is optimally balanced to achieve low thermal conductivity and high permeability, as the texture of the clay has minute pores that trap the heat while permitting the exchange of air, which prevents the tea from becoming stale.

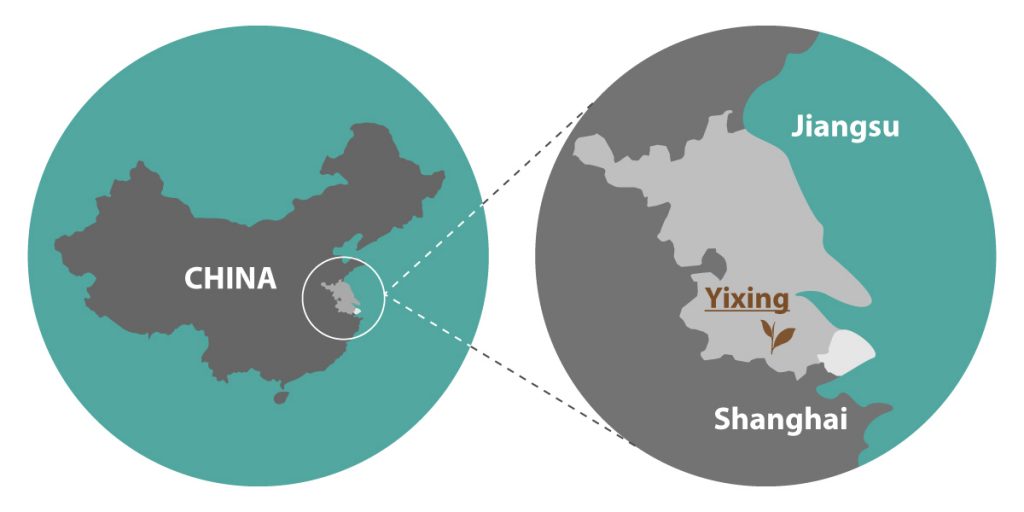

Zisha (‘purple sand’) describes the reddish-brown color of the sedimentary soil which settled in ancient lakes and is now buried deep underground. The clay is compressed under heavy sedimentary rock formations throughout the Yixing region, southwest of Shanghai, in China’s Jiangsu province. Huanglong Mountain near Dingshu township has been the source of high quality purple clay ore for centuries. The mountain itself is rather ordinary – neither grand or pretty – but it is 350 million years old.

These teapots are prized because their unglazed surfaces absorb traces of the beverage and develop a patina, which enhances the taste, color and aroma of fine tea. Generally, Yixing teapots are single-serving pots with 100-300ml capacity, considered small by western standards. Flavors concentrate in the pot and are better controlled during brewing, then gradually revealed through different rounds.

Preparing purple clay

Preparing the clay is a lengthy process and closely guarded trade secret. In the past, workers descended into the mountain to carry the Zisha ore by hand. The ore was then left in the open for years, allowing temperature changes from season to season to break it down naturally. Workers then pared the piles, sorting the pieces with the highest concentration of the purple clay. The process was so inefficient it becomes a ritual.

The next step is to screen the clay, isolating particles of the finest grit size, and then mixing it with water in a cement mixer to create a thick paste, after which it is piled into heaps and vacuum processed to remove air bubbles and some moisture. The quality and quantity of water is critical because it determines the quality of the stoneware products produced. After processing, the clay is then ready to be shaped.

Teapot making process

Purple clay is not only more sensitive to humidity and temperature, but also much harder in consistency than common clay, thus it requires advanced skills of artisan potters to work with the material. Potters begin by beating a lump of aged clay into a flat sheet using bamboo tools. The walls, bottom and lid are cut from the same sheet of clay. The masters then shape the clay entirely by hand or with wooden spatulas. The body, spout, handle, lid and feet are all made separately, then assembled on a simple, hand-turned wheel, stuck together with a simple mixture of clay and water.

How to value a teapot?

Consumer teapots are usually classified into three categories by techniques: handmade, partially handmade and molded teapots. An entry-level handmade pot sells for RMB ¥2,000, around USD $300, while the more expensive pots will sell for thousands.

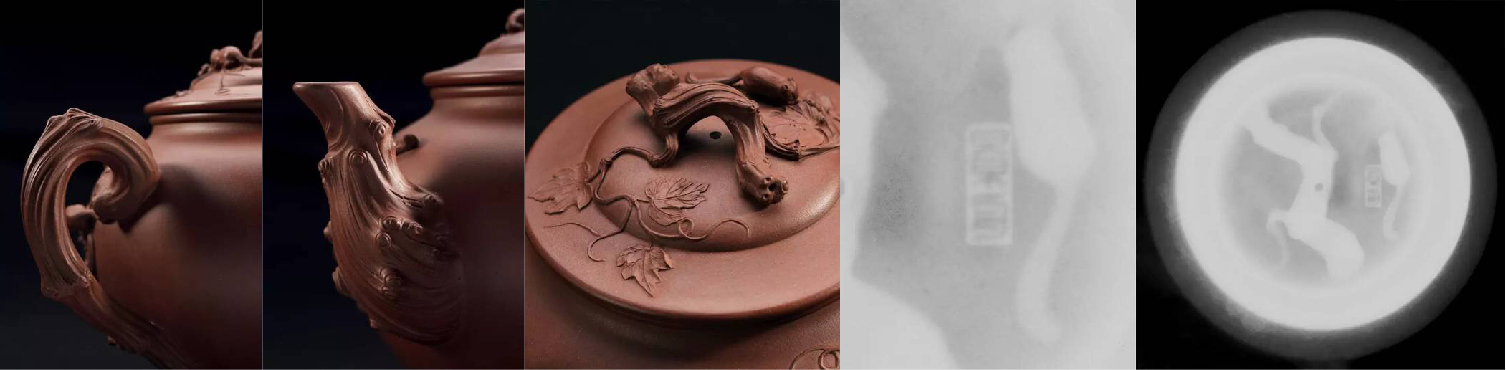

Style-wise, the pots are grouped into three major styles: the most common are smooth-bodied pots called ‘Guang Qi’; the most ornate are decorative pots called ‘Hua Qi’; and those with a distinctive petal vein pattern are called ‘Jin Wen Qi’. Smooth-bodied pots, embodying abstract geometric shapes, are sub-divided into square- and round-shaped works, demonstrating beauty in brevity, the ‘introvert elegance’, which symbolizes the pursuit of the ultimate human spirit. They are designed to reflect the simple relationship between the teapot and the tea drinker.

In contrast, decorative pots resemble real life objects. The artistry is to depict real world objects as complicated carved shapes with lines that suggest their essence without merely copying the shape. Decorative pots require techniques such as piling and carving to imitate shapes of things in life and nature, reflecting the awareness of artists of their relationship with the environment.

We say making decorative pots is like doing addition in math. We use piling and shaping techniques to add things onto the pot body. And for smooth-bodied pots, it’s just the opposite; we are doing subtraction – removing all the non-essentials. – Rong Jiang, one of the seven most distinguished Zisha master artists

Unethical manufacturers complicate the purchase of authentic pottery. Sellers are known to mix in questionable chemicals to counterfeit clays. To authenticate pots from Zisha masters, one has to send a pot to experts or refer back to the masters themselves. Zisha masters can tell which pot they made because they placed a mark on the pot known only to themselves.

The wait is as long as two years for pots commissioned by a master craftsman. Jingzhou Gu, one of the founders and Deputy Director of Research and Technology at the No. 1 Yixing Factory, now deceased, was the most accomplished master artist. In November 2015, Gu’s nine heads cherry blossom teaset, made in 1955, was auctioned for RMB ¥92 million (USD $28.75 million), at the 2015 Beijing Dong Zheng Autumn auction.

No.1 Yixing factory – quick facts:

- Yixing clay for the No.1 Yixing factory is exclusively extracted from the No.4 well at Huang Long Mountain.

- The factory’s antique kiln was destroyed in 2002, making it impossible to replicate teaware.

- The No.1 factory was founded in 1955 by seven prestigious Zisha masters: Yungen Wu, Shimin Pei, Ganting Ren, Yingchun Wang, Kexin Zhu, Jingzhou Gu, Rong Jiang.

- Peak production was during the years 1977-97 when the factory produced miscellaneous articles for daily use, notably teapots. Most of these works were exported.

Consumer advice

If you are in the market for a new Zisha pot, think about one type of tea that you want to make in your teapot. If you want to buy a Zisha pot for puer, then choose a bigger pot allowing comfortable expansion for big leaves of puer tea inside the teapot. Ergonometry is also important: the mouth of the teapot must align with the center of the lid and the handle and the proportion of weight in the mouth needs to balance with the proportion of the weight in the handle.

Teapot varieties: color, texture, shape

Despite the name ‘purple sand’, Zisha pots can exhibit different colors. Zisha is divided into three categories – red (Hong Ni), purple (Zi Ni), and green (Lü Ni), extracted from different strata layers from Huanglong mountain, and each type can be subdivided further.

Differences in texture are achieved by using different mesh sizes of sieve when filtering. It’s a matter of personal preference whether to choose bigger or smaller mesh, depending on the look one wants to achieve. Using a finer mesh (100 mesh or higher) produces a finer, smoother, shinier finish, while a lower grade mesh conveys a more rustic, minimalist tone. Neither the age of the raw material nor the fine mesh enhance the value of these pots.

Smooth-bodied teapots come in a wide variety of shapes:

Yun Qu 云曲 Vol.: 250ml. Surface diameter: 8cm. Body diameter: 15cm. Height: 7cm.

Following are illustrations of teapot shapes that are most popular among collectors:

Tea Market

Get More Value from Your Tea: BRU Maker One

+41794574278

Jacque's Organics

(647) 804-7263