Tea once traveled the most daunting journey of any plant on the planet. Few tea drinkers know the story of how tea spread to every nation from its origin in the mountains of China. Traders for 13 centuries loaded tea on the backs of yaks, mules, horses, sheep, and man. It took months for caravans of tea to find their way from what is now Yunnan and from Sichuan, China along narrow trails ascending to the highest of highlands, the Tibetan Plateau. Along the way, this eternal fuel of the spirit, this simple bitter leaf, worked its magic as stimulant, medicine, panacea for remote peoples. The Tea Horse Road (called Cha Ma Gu Dao in Mandarin and Gya’lam or Dre’lam in the Tibetan tongue) is peopled with characters whose tenacity and generosity in sharing precious oral narratives provide a glimpse of adventure and the blood spilled transporting tea on a route that reaches the sky.

The Source

A Hani woman tracks through a forest of ancient tea trees in Xishuangbanna, one the places where the original tall forests of tea can be found. To the indigenous peoples, (called “la” by the Hani) tea was more than a commodity. The plant and its leaves were considered sacred and used as medicine. Trees are worshiped as part of the tapestry of life.

There are many local “recipes” for tea in southern Yunnan. Garlic and peppercorns, orange blossoms, and even chilies are added to the brew. Some mulch tea leaves in bamboo husks and place them over fire, stewing the leaves. The result is a roast-flavored concoction said to be good for quelling fevers and reducing inflammation.

Locals seldom consume the ripe or “cooked” Shou Puers, preferring instead the vegetal pungency and natural forest flavors of the raw or Sheng version of the big leaf trees.

Abohors

Few remain in the most remote lands of an isolated realm. The Abohors count luxuries differently than most: tea, salt, and resin are exalted items of trade.

This young woman (pictured right) and her clan lived at 16,400 feet (5,000 meters) along a portion of the Ancient Tea Horse Road. She hosted our team with two of the three luxuries, tea and salt, for two nights before crossing the 17,700 foot (5,400 meter) Nup Gong La mountain pass.

During the height of trade, host families (called “netsang”) offered grazing, warmth, and supplies to traders in return for tea.

The Last Muleteers

The history of the Tea Horse Road is heard in the oral narratives of the muleteers, this last generation of traders, and travelers along the route.

A life of trade and ushering caravans across the top of the world was the only way to explore the world for many. Tibetans are suited to the brutal journeys through the Himalayas. Onward they pressed to destinations that included Lhasa, Chamdo, Xigaze, and even Kathmandu in Nepal and to Sikkim, India. Traders and muleteers would buy and trade items, returning to their communities with these items, which in turn would be traded.

The 935-mile (1,500 kilometer) journey from Shangrila to Lhasa took anywhere from one to two months depending on weather, the presence of thieves, and the strength and endurance of the travelers. Misfortune was ever present. Entire caravans simply disappeared in blizzards and landslides, taking with them their cargoes of tea.

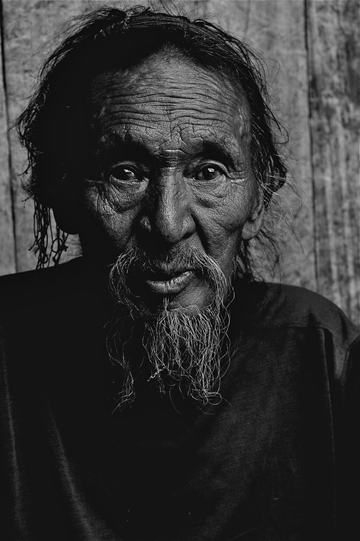

A Bulang tribesman in Yunnan, China

The Bulang

Pictured above is an elder of the Bulang tribe (also known as Blang or Pu people), guiding us through a stifling forest of tea (the background forest is entirely made up of tea trees). The Bulang, along with the Wa, Lahu, Hani, and Dai occupy much of the Bulang Mountains and basins of southwestern Yunnan.

Thought to have once occupied areas around the Mekong River Valley, the Bulang moved into the highlands. Along with many of the minorities of southern Yunnan, theirs was largely an animist belief system.

Teas from the Bulang have traditionally been known for strength and astringency, and it is often considered disrespectful to wander through their tea forests alone without a guide or elder as the trees are considered sacred.

Khampas

There are two main tributaries of the Tea Horse Road, with dozens of striating feeder routes intersecting and splicing off, only to reconvene and break apart once again. The older of the two routes began in southwestern Yunnan. A second road led from Sichuan, gaining prominence in the Song Dynasty of the tenth century.

Each route connected the tea-hungry market towns of Tibet, and both had to pass through huge and daunting landscapes, home to the eastern Tibetan Khampa nomads. Feared, misunderstood, and utterly tough, these clans were often the greatest challenge and the most able guardians of the tea routes. Gifted thieves who also protected the caravans, these nomads were essential to the history of the Tea Horse Road. They craved tea more than most but bandits would think twice before targeting a trade caravan protected by even a couple of these nomadic guardians.

The Guardian

Formidable and notorious in his day, Tenzin (pictured right) was a simple muleteer who rose to become a guardian of monastic caravans, who themselves had a huge part to play in the Tea Horse Road. Tenzin’s work was to ensure that tea and other commodities made it to their destinations intact.

He recalled how ingenious thieves would in the cover of darkness ignore silver and other items of worth, targeting instead the priceless tea. Their strategy was to slice open the leather satchels, remove bricks, and balls of tea, and replace them with stones or turf replicating the missing weight almost exactly, before sewing the leather satchels closed.

“Nothing was as precious as ‘ja’ (tea) as it had worth in any home or community. Tea was everything,” said Tenzin.

Dawa

During our 7-1/2-month journey along the Tea Horse Road, Dawa (pictured above) came to personify the route’s inherent magic and physicality. As a young man, he endeavored to see more of the world, joining a caravan from his village, Melixue, within the sacred Kawa Karpo’s breath in northwestern Yunnan.

Our team spent a full day interviewing this epic “la’do” (a muleteer in Tibetan, meaning “hands of stone”) and he warned and, in fact, prophesied that our crossing of the famed Sho’la Pass would be difficult.

To be successful as a trader, Dawa insisted, one needed “to respect and understand how to navigate nature, and to never sell tea too cheap.”

Lands in the Sky

For the nomads, tea was invaluable. Centuries of dynasties in ancient China used tea as tribute to keep the feudal tribes of the Tibetan Plateau at bay. Tea (with its accompanying health properties) became an utter necessity, and every market town and many nomadic communities welcomed the seasonal caravans.

One of the items most coveted by Tibetan women was the apron (called “pom’den”), which would be brought back from Lhasa from weavers along the route. Gifts to keep the various nomad clans content were vital as they controlled vast swaths of the highlands through which the caravans must travel. If one maintained good relationships with the nomads, one had a powerful ally.

Omu

Omu tends her yaks fortified by “bod ja” or Tibetan Tea. This tea is churned after stewing and cooked with butter and salt, sometimes with roasted barley powder (tsampa) mixed in. Calories, proteins, and stimulants all blend together in a timeless concoction that is consumed at all hours of day to provide endurance at altitudes above 15,000 feet.

Tea bricks, known as “chap’so” or “jap’so” and wrapped in bamboo, birch bark, and banana skin, can still be seen in many homes on the Tibetan plateau.

Golok

An elder of the Golok nomadic group near Maqin in southern Amdo (Qinghai Province) reflects upon trade through her people’s lands (see right). Many of the elders traveled huge distances trading tea, salt, and even pashmina across the Tibetan Plateau.

Trading families, individuals, and businesses all had relationships with those whose lands they passed through. It was no different with the Golok, who were fiercely independent and territorial. Caravans often paid informal taxes or tithes to the nomad families for safe passage through their lands. It was rare that anyone would dare threaten a caravan that traveled under the good graces of a Golok family.

Taxes and tithes were often (and preferably) paid in tea; the very commodity that was being transported.

Ever-Burning Fire

Fire is rarely quenched within the yak wool tents of the nomads. The kettle is fed with water in readiness for a serving of tea.

A wonderful quote of the Himalayas exemplifies the importance of tea for the nomads, who rarely turn away a fellow traveler or guest without at least a cup of tea, “If tea isn’t offered, a relationship isn’t offered.”

Heights

Two nomadic shepherds near Horchuka in western Sichuan province tend their herds at altitudes few can contemplate living (pictured below).

During their long journey, tea would undergo a transformation. What began as simple “green” leaves compressed into bricks, balls, and tubes would often emerge significantly changed. Though the tea would remain the same on its long journeys from the origins, the muleteers and carriers (yak, mules, horses, and even sheep) would change. As altitudes and cultural significance changed along the route, so too would the transporters. Altitude, humidity, the temperature of the animals carrying the teas, and time itself would all contribute to the final flavors. Tibetans rarely cared whether there were stems or other bits within the tea. Provided it was strong with astringency, they were content. As one old trader commented, “The best teas came from Ja-yul (tea country), which referred to Yunnan province. The others didn’t have any power and we needed to infuse for hours to get any flavor.”

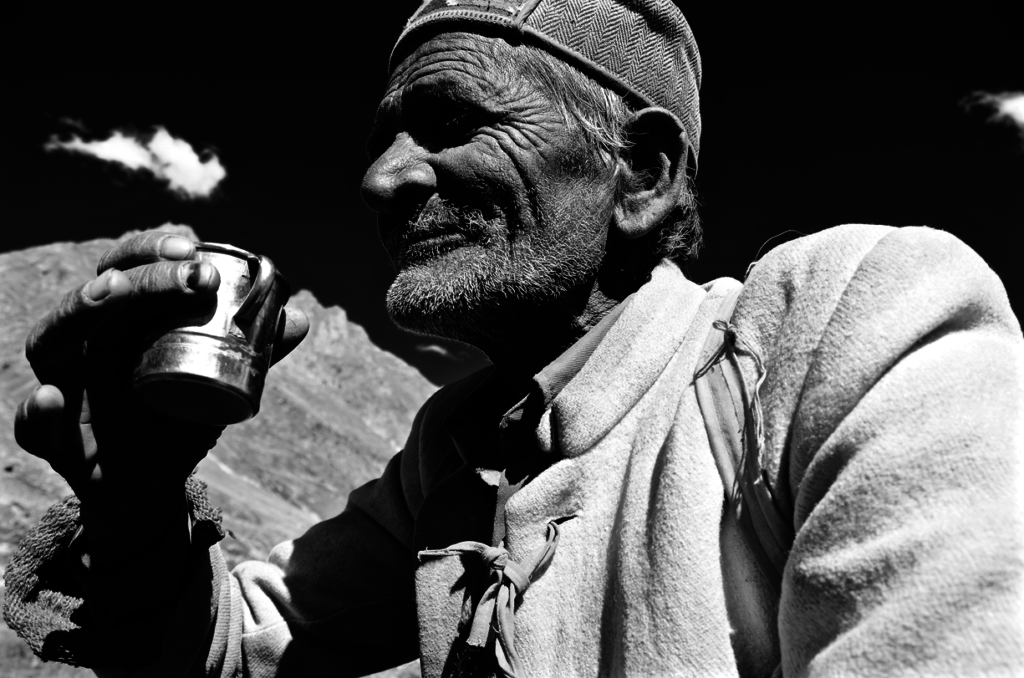

Biari

A shepherd from the remote Chandra River Valley in Himachal Pradesh (pictured below right) sips a tin mug of chai from our camp. Working with his herds for over a half-century, Biari Singh’s knowledge is entirely place and land based, but his need and appreciation of tea, is parallel to that of so many with so little in the Himalayas.

When asked about the trade routes, he sat down and politely asked for tea…few words are spoken in the mountains without tea in hand.

The Chandra Valley itself lies along old trade routes that transported salt, tea, and pashmina in India’s Himalaya. Tea’s vitality here is epic, even if the tea itself is different. Biari’s preference for cardamom and peppercorn-laced milk tea with milk and ginger using leaves from Assam may differ but he has encountered the teas that traveled “from far to the east.” He referred to the tea from Assam as the “bitter leaves.”

Lady of the Pass

The lady pictured above lives with her daughter’s family along the route still. Her black wool tent was one of the last homes before the mighty Nup Gong La (West Gate Pass) within the Nyangqentanglha Mountains east of Lhasa.

When we arrived at her family’s tent, she asked “What have you brought me?”

In the past, host families were like favorite children currying favors, commodities, and information from the muleteers, who were like traveling superstars of the mountains.

One of the vital roles of the hosts was to share information about the route and weather, another example of how relationships were crucial, particularly in these most remote of lands.

The wait

A woman in her eighties (left) in southern Yunnan recalls an old romance 60 years ago with a tea muleteer. She recalled meeting him when he came into town with loads of tea strapped on to a mule team. She mentioned that he never wanted to be out of eyesight of his precious cargo, even for a moment. He promised to return for her but never did.

Beyond the economics, tea trade revolved around relationships established between cultures that formed binding links between empires and communities, however small and seemingly insignificant. In time, tea spread to every point of the compass through the efforts of mortals. For thirteen centuries, the flow of tea continued; no war, drought, nor shifting political landscape ebbed the flow of tea.

The Walker

For almost four decades, Tenzin (a common name in Tibetan meaning “the holder of teachings or Buddhist Dharma”) bought, traded, and wandered along the Himalayan corridors. Fluent in several languages, he spoke endearingly of the Tea Horse Road as a corridor into other worlds. “How else could I have seen other places?” he wondered.

“When you travel over the passes and through blizzards, you appreciate how small you are and how nature can ‘take’ you at any moment. I also think the journeys added to tea’s value, having traveled so far over so many lands.

“Those that received and consumed the teas often thought about these journeys and so tea has always been considered special,” he added.

Jeff Fuchs spent seven and a half months traversing the Tea Horse Road. His travels were featured in a Canadian Broadcasting Corp. (CBC) documentary that aired in July 2017. His book, Ancient Tea Horse Road: Travels with the Last of the Himalayan Muleteers, is available in hardcover and on Kindle. Jeff is founder of Canadian-based Jalam Teas.

See full bio.

Listen to his CBC Podcast | CBC Eye On Canada (check for documentary updates)

Tea Market

Get More Value from Your Tea: BRU Maker One

+41794574278

Jacque's Organics

(647) 804-7263

HI Jeff

what an amazing article with so much heart in it. Renee

This is one of the best narratives I have read. Thank you

The writing and photography are exceptional!

What a great narrative and photos! And what an adventure to undertake! Love it!