The Little Tea that Could

Kangra Valley, Dharamsala, India

The Other Himalaya

A scant 2,000 kilometers west of Darjeeling, on the opposite side of the Indian subcontinent, lays a scenic valley of the Indian state of Himachal Pradesh, a place steeped in Hindu mythology. The Kangra Valley is nestled in the Dhauladhar (Hindi, White Mountain) range of the western Himalayas at the center of the ancient land of Trigata, where Rajput kings of the Katoch dynasty ruled from the great Kanga fort.

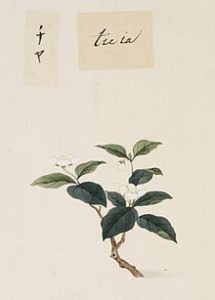

The valley is also known for the Kangra School ![]() miniature painting, whose works of brilliant color and line as fine as a hair’s breadth graced the halls of the Rajput kings during the 17th and 18th Centuries.

miniature painting, whose works of brilliant color and line as fine as a hair’s breadth graced the halls of the Rajput kings during the 17th and 18th Centuries.

Geographically cut off from the Punjab plains by mighty rivers, hilly terrain and the fierce armies of local kings, Kangra became part of British India in 1849, at the conclusion of the second Anglo-Sikh war. It was the last Indian Territory to fall to the British, the final Indian jewel in the crown.

A more recent profoundly influential event in the district was the arrival of Tenzin Gyatso, the 14th Dalai Lama, in 1959. An influx of thousands of Tibetan refugees followed. Their Buddhist teachings attracted many to the valley, and Dharamsala became one of the most recognizable place names in India.

Tea Takes Root

In the same year as the Kangra accession, British botanists conducted a survey of the valley to see what could be commercially grown there. Tea was a “hot” item at the time, with on-going trial plantings in Darjeeling, Dehra Dun, Almora, and the south. China tea trees (C. Sinensis sinensis) were brought in from nurseries in the United Provinces and planted in four locations in the valley. The tea plants thrived particularly well in Dharamsala and Palampur.

The first commercial tea plantation was founded in 1852 east of Palampur at Holta, and by the opening years of the 20th Century it had reached its nadir. It was recognized for excellence in London, Barcelona, and Amsterdam, where Kangra enjoyed pride of place on the best tables of Europe.

Force Majeure

Fifty years into a brilliant career, Kangra tea and the people of the valley were struck by calamity. Early in the morning of April 4th, 1905 the Great Kangra Earthquake hit, at 7.8 on the Richter scale, the third most powerful ever on the subcontinent, and only the fourth great Himalayan earthquake in 200 years. In seconds, more than 20,000 people lost their lives, farm animals were killed, buildings flattened, irrigation systems destroyed.

British-owned tea factories with their big imported machines were wiped out. Running for their lives, virtually all of the British tea planters abandoned the valley, selling their ruined gardens to local residents.

The new Indian chaiwalas did not have the resources to rebuild factories and restore gardens, so many reverted to the ancient hand manufacture of green tea, which required a simple skill set and only basic technology.

The partition of India into the Republic of India and the Dominion of Pakistan occurred in 1947. With a stroke of the pen, Kangra Valley was removed further from its markets to the east.

By the time I arrived in Palampur as an American Peace Corps volunteer in the autumn of 1964, Kangra was as a “green tea zone.” I often observed coolies hauling huge woven bamboo baskets of made tea and fresh-plucked leaf in Palampur’s central market, where it was taken by bus and truck to Pathankot, Amritsar, Punjab; thence to Afghanistan, Iran, Iraq, and the Middle East.

The region no longer produced black tea for export. It had been eclipsed by Darjeeling, Assam, and Nilgiri.

The Soviet Union’s war in Afghanistan (1979-1989) created another barrier to trade with Central Asia. Then, in 1992, the USSR, one of India’s largest tea trading partners, was dissolved, and that market evaporated.

A Change of Fortune

Until 1966, Kangra district was part of Punjab state, the “bread basket” of India. It was a “hilly area,” and consequently of marginal economic and political importance.

Kangra’s political clout changed when it joined Himachal Pradesh (HP), a “hill state” with a largely rural population. Because it was comparatively densely populated and resource-rich, HP paid more attention to the chronic economic issues plaguing Kangra, including the underdevelopment of agriculture and tourism.

In 1994, the Tea Board of India set up a tea auction house in Amritsar, Punjab, devoted to the sale of Kangra tea. The state established a tea research and promotion center at Palampur, and between 1964 and 1983 four cooperative tea factories were built to process leaf of small growers. Government schemes offered subsidies and training to tea small growers.

Despite these profound efforts, by the late 20th Century, the Kangra tea industry was succumbing to illness. Upward pressure on land values encouraged planters to abandon underperforming gardens for more profitable uses such as those related to tourism, hospitality and housing.

More than 95% of Kangra tea is grown by small-holders without factories. Most lack formal training. They use agents to collect their leaf and sell it on to bought-leaf factories. This results in low prices to planters and lack of consistency in quality at the collection point.

Survival

The Amritsar auction house closed in 2005 and various government schemes failed to make significant inroads. Out of four coop tea factories only the one in Palampur exists today. However, it would be wrong to say efforts were wasted. In the end, the patient lived.

By the turn of the 21st Century, financial interests, business persons and technical talent from other areas of the country began to show interest in the troubled tea gardens of Kangra. Some of these individuals are scions of families long associated with tea and some are outsiders, turn-around experts attracted to Kangra tea as potential premium niche product.

To check out the situation in Kangra, I flew out of the early morning smog of Delhi on a narrow-bodied Bombardier Q400 turboprop, and in 95 scenic minutes arrived in the clear cool mountain air of the Dhauladhars.

This was my fourth trip to Kangra and the tenth to India. Each time I return to the valley, it seems closer to New Delhi, less charming, more crowded, polluted. Nothing short of global warming, however, can change the inspiring vista of jagged snow-capped peaks that follows one like the moon.

The Kangra tea-growing region, which covers about 2,300 ha, runs across the district from Pathankot, Punjab, in the west to Bir, HP in the east, and follows the route of National Highway 20. Altitudes range from 700 to 2,000 meters above sea level. March to October, temperatures range from 13 to 35 degrees Celsius. Rainfall totals from 2,300 to 2,500 mm.

Dharmsala Tea Company

The Dharmsala Tea Company (DTC) ![]() is located near Kotwali bazaar, Lower Dharamsala. The estate was founded in 1882 by the Mann family and is now owned by third generation Mann, S. Gurmit Singh, a Delhi industrialist.

is located near Kotwali bazaar, Lower Dharamsala. The estate was founded in 1882 by the Mann family and is now owned by third generation Mann, S. Gurmit Singh, a Delhi industrialist.

The company has three gardens totaling about 70 ha: The Hoodle rises 4,000 ft. (1200 meters), the Mann, 4,500 ft. (1370 meters) and the Towa, the most remote, at 6,000 ft. (1825 meters)

I dropped by the elegant owner’s bungalow for a cup of tea, a romp with the Mann dogs and a talk with estate manager, Aman Pal Singh.

The manager comes late to the 140-year-old company, but says he joined up primarily to help restore cup quality to the highest level possible.

Singh worked for several decades at the Darjeeling estates of Ambotia, Orange Valley, and Moondakotee, and moved to Kangra in 2010 to assist the Mann’s. He emphasized 90% of the turnout is orthodox black tea; the remaining 10% are green teas, oolongs, white teas, and scented blends exported to Germany, UK, Holland and France, as well as, U.S.

I asked the manager whether it is rational or useful to compare Kangra tea with Darjeeling. Singh emphasized that Kangra and Darjeeling are the only tea-growing regions in India with 100% China Jat. Both regions are hilly areas verging on the Himalayas and enjoy similar, though not identical, growing conditions.

Differences in history are consequential, and so is experience and training, but Singh asserted, “If you process high quality China leaf, hand-plucked from healthy bushes, the way it’s done in Darjeeling, you will get a tea that is ‘as good as,’ if not identical to, Darjeeling.”

We adjourned to the spotless, little tasting room at the entrance to the company compound and cupped a sampling of fresh teas.

The autumnal FTGFOP1 had good body, moderate astringency, an earthy, minerally and herbaceous character.

The spring tea had a complex upper range, a bouquet of high-notes, including floral nuances. It was light and delicate, with the low astringency characteristic of Kangra.

Spring flush Kangra teas exhibit a muscatel nose, but it is less pronounced than in Darjeeling. If Darjeeling is the “Champagne of tea,” Kangra is the “Asti Spumonte.”

A hand-rolled oolong was warm and appealing with a slight bouquet of flowers. It was not very green and had a pleasant black tea aftertaste which I’ve come to expect from an oolong made in a black tea factory.

Himalayan Brew

The Raipur Tea Estate, planted in 1850, is located about seven and a half miles southwest of Palampur on NH 20. It has been owned and operated by the Sud family since 1894. The present owner is fourth generation scion Rajiv Sud. He and his wife, Richa, produce Himalayan Brew, ![]() a brand of loose leaf tea and teabags with a very modern feel.

a brand of loose leaf tea and teabags with a very modern feel.

Sud was living in Singapore, where he was an officer in the army, when he made the decision to return to India to take over the family tea garden and thoroughly modernize it.

He and his wife took over the garden and factory in 2009, putting in new machinery, including a tea-bagging machine, creating new tea and herb blends, as well as an extensive array of masala chai blends in a range of contemporary retail packs. The emphasis is on premium quality tea and herbs in fresh blends and scented tea based on tea and herbs grown in Kangra.

Wah Tea

Wah Tea Estate, ![]() outside Palampur town, is arguably the best-known garden in Kangra district, and one of the hardest to find. As my taxi driver said: “Wah is not in the middle of nowhere, it is to the north!”

outside Palampur town, is arguably the best-known garden in Kangra district, and one of the hardest to find. As my taxi driver said: “Wah is not in the middle of nowhere, it is to the north!”

It was late in the day when Surya Prakash, the estate manager, flagged us down at the garden entrance. The sun was beginning its descent, shadows lengthening over trim rows of tea bushes. Columns of tired tea pluckers ambled lazily down the drive on the way home to make fresh warm chapattis.

Prakash’s great grandfather launched the Mann family tea enterprise in the 1950’s, buying gardens in Assam, Darjeeling, and Kangra. The period immediately after partition must have been an ideal time for that sort of acquisition.

Prakash’s father and mother, third-generation chaiwalas, run the Glenburn Estate, a Darjeeling garden south of West Bengal’s border with Sikkim.

Walking down the drive intersecting an expanse of well-manicured tea, the fourth generation Prakash tells the story of the Wah Estate. A descendent of the Nawab of Wah, a place now in

Pakistan, purchased land in the Kangra Valley to establish a tea estate. He named it Wah, after his family’s birthright. After partition in 1947, east Punjab went to the Republic of India so the Government of India acquired Wah from the owner who left for newly-created Pakistan. The Prakash family purchased Wah from the government in 1953.

Wah Tea Estate is the largest single-owner garden in Kangra, with a total land area of 526 acres. It produces 150,000 kg of tea annually.

Prakash explains he has recently taken over Wah reins from his father, Deepak, who is “close to retirement” and focused on business at the company’s Kolkata head office.

Under Prakash the factory is diversifying production to include classic green tea, premium black tea, pure Chinese-style, pan-fired green tea, scented green tea; scented black tea, tea-herb blends and tisanes. He has put more emphasis on value-added, branded packaging like others in Kangra.

A second stream of income comes from the Lodge at Wah, a new homestay at the tea estate. The sprawling, hand-built earthen building was designed and built by Deepak Prakash.

It has seven bedrooms with garden views, a large family dining room and a kitchen which offers traditional Indian gourmet food and regional specialties. Daily room and board is $140 (INR9, 000).

The Niche

I left Kangra Valley with a fresh view of the gardens and factories. It’s not a bed of roses, yet, but the industry is turning the corner, one resuscitated, reinvigorated garden at a time. Life support is coming in the form of fresh capital investment and – more crucial – the migration of fresh, young talent and experienced management from outside the region. Cup quality is improving and the larger tea gardens, especially those with factories, are updating practices. Kangra tea got geographic (GI) certification in 2005.

Kangra may always be a niche, rather than a volume, producer, but premium leaf from recognized tea-growing regions is the niche that is increasingly driving the market. Western Himalayan teas are back in business after a century of dampened successes and much travail.

Tea Journey sent specialty tea pioneer Frank Miller on a tour of India in search of exceptional tea. During his travels he explored what he calls the Other Himalayas, a tea growing region in the Kangra Valley in Himachal Pradesh. The quantity of Kangra tea, which retails at prices 40%-50% higher than even Darjeeling tea, has decline significantly according to the Tea Board of India. While 2,300 acres are recorded as tea growing properties, only 1,150 acres of tea gardens are being properly maintained. In Palampur as many as 300 to 400 acres of gardens are lying abandoned and 600 acres are neglected. Five factories in Dharamsala, Palampur, Bhwarna, Baijnath, and Bir produce only 1.1 million of the region’s 2.0 million kilo potential. This is part three of Frank’s Tea Journey.

Tea Market

Get More Value from Your Tea: BRU Maker One

+41794574278

Jacque's Organics

(647) 804-7263

Excellent research

Amazing! Ive been doing some research on the Kangra Valley and its safe to say that this article helped me a lot! Great research done.

Great

I appreciate your article because I live in Kangra and have a green tea online business from last couple of years

You can find best Kangra green tea online http://www.kangravaleytea.com

Kangra tea did not originate in India as has been picturised. Kangra tea has been planted using tea plants stolen from China, while the plants from which local tribes used to make tea at Bashahar in Punjab in Imperial India has been ignored by the botanists of East India company for unknown reasons. Bashahar tea was popular in Tibet, Nepal and Afghanistan.

Show more