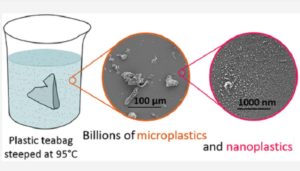

Plastic in tea bags is the subject of one of the most attention-grabbing reports on tea in recent years. It appeared in late September 2019 and within a day was being widely posted, in general news sites, and tea, food and medical posts. It describes the finding of a small scale, focused study that the plastic breaks up into billions of “micro-particles” and “nano-particles” when brewed at the normal heat and for the normal time.

Sound the alarm?

Here are typical reactions: “Plastic pollution is in your cup of TEA.” (Daily Mail), “Invisible health hazards” (Newsmax), “Contaminated” (Bioplastics News), “A shocking report” (Narcity). The idea of tea creating a flood of plastic pieces small enough to pass through cells that flow immediately through your body is certainly arresting, though the report emphasizes that there are no known health hazards from plastic particles.

The unknowns are the alarm bell that the widespread coverage of the study reflects. The “billions” figure conjures up images of a chemical surge of attack. As for “nano-particles”, whatever they are, they sound mysterious and dangerous. When you drink common brands of bagged tea what happens to these particles? Are they yet another threat to safe health like many pesticides? Do they build up in the body over time? Do they create the internal inflammations that are a frequent precursor of cancer, though not a known cause. Plastic waste is a major environmental threat – is it a biological one, too?

Plastic particles

There are three standard measures of small units of materials that include chemicals, drug delivery systems and pollutants in the atmosphere:

- Macroplastics are chunk-sized and clearly visible and can be captured and disposed of easily. They rarely directly affect the food chain. They break down under the influence of hydrolysis, mechanical and physical degradation and sunlight into micro-particles. They are not, however, biodegradable. They get smaller but stay for lifetimes, mainly in our oceans.

- Micro-particles are grain-sized and most commonly defined as those that are 1-5 millimeters in size. Most of the huge Garbage Patches of oceanic waste are full of this floating debris, which may not show up on satellite images, because it is a floating soup. The largest of the main five, the Great Pacific patch, is twice the size of Texas and three times that of France.

- Nano-particles range from powder-sized to invisibly small. They are commonly defined by standards groups like ISO as 1 to 100 nanometers in size. A nanometer is a billionth of a meter. A human hair is around 80-100,000 nanometers in width. They come in many varieties of shape. They have been widely used as an abrasive in cosmetics, where an 8-ounce jar may contain 4 trillion nano-particle microbeads. (Canada and the US have banned their use, a signal of the concerns of unknown hazards.) A primary application is in nanomedicine. Drug delivery systems loaded onto particles engineered from botanicals, silica, polymers and metals can penetrate most of the body’s membranes and cell barriers with widely varied therapeutic impacts – and toxicological hazards. The tiny particles can enter the food chain directly and spontaneously. That’s where the concerns raised by the McGill University study begin. They differ in one key aspect from nanoplastics: they must be biodegradable in order to release the drug. The curse of plastic is that it lives on for centuries.

There are complex differences between micro- and nano-particles beyond size. The smaller particles have a high surface-area-to-volume ratio that may facilitate other molecules, including ecotoxins, attaching to them. They penetrate the cells and membranes of shellfish in just hours; larger particles are unable to make this intrusion and aren’t digested. In medicine and industrial nanotechnology, the dynamics of classical physics get dominated by quantum physics, which is perhaps best summarized as “really, really weird.”

The McGill research in no way addresses the biodynamics of plastic. It suggests that there are surely risks to be addressed that have been understudied and are completely unfamiliar to tea drinkers.

Nothing to be concerned about?

The counterview is that there is no evidence of harm from plastic particle ingestion so muffle the alarm bells. That’s the stated position of the World Health Organization. The plastic is excreted and found in human feces without affecting the body’s cells or remaining in internal organs. The Tea and Herbal Association of Canada issued a statement immediately following the publication of the McGill study that the two plastics in the bags have been approved as entirely safe in hot food and beverages. The rapidly emerging innovation path among the leading tea bag brands is to get rid of plastic entirely and reports on the article are misleading in their frequent statements that the reverse trend is dominant.

It is important to note that the pyramid tea bags constructed of “silken” nylon and PET (polyethylene terephthalate) used in the experiment represent only 5% of the total tea bag materials market. Pyramid bags made of PET are used to make cold brew coffee, tea, herbal infusions and to hold spices in cooking. Most tea and coffee filter materials are made from abaca, a natural fiber grown in the Philippines and Ecuador. Traditionally, these bags are sealed with plastic – either polypropylene or polyethylene. The plastic fibers form part of the paper and are bound (fused) within it.

The billions of particles figure is a matter, literally, of perspective. It sounds so huge but adds up to tiny total volumes. The amount of plastic in a single bag is around 60 micrograms – 60 millionths of a gram. Change the headlines from “Tea bags release billions of particles” to “millionths of an ounce” and the emotive reaction is surely more muted. But the figures are exactly the same.

The authors of the study have expressed their surprise in finding just how many plastics particles they found in the bags’ composition. They expected “maybe” a few thousand. Researcher Nathalie Tufenkji, attributes much of this to counting far smaller particles than other analyses. The researchers used electron microscopes to estimate the numbers. They have a magnification of 10 million times, versus the 2,000 or less of light microscopes.

This helps explain the lack of consistency in comparisons with estimates of particle counts for foods. There is no reason to question the McGill team’s figures. They used highly sophisticated equipment, methods and math. A question worth considering is that the older data overlooks many particles in its samples. The perspective points up that there is much that we just don’t know, aren’t measuring and have not investigated.

In the same month as the McGill study was published, another Canadian University of Victoria researcher reported that he had been able to locate only 26 studies that provided data on particle counts, with none for fruit, meat and vegetables. He presented a composite estimate of human micro-plastic consumption: 39-52,000 micro-particles a year per person for nutrients like fish, salt, sugar additives and water. Bottled water might add as many as an extra 92,000. Breathing accounts for another 35-69,000 – particles in the air, from many environmental sources.

The McGill study

The research study is a small “one-off” investigation carried out at McGill University in Montreal. It was intendedly exploratory, stimulated by Tufenkji’s thought when buying a tea served in a high-end “silky” bag containing plastic that it was likely to break up. The research addressed how much so.

The design is simple and is open to scientific criticism, though it seems sound in its methods and statistical analysis. Small sample studies are notoriously unreliable and too often unrepresentative of the fuller population. Here, the team picked four tea bag brands known to be made of plastic essentially at random. The tea was removed and the bags heated in water at 95˚C for five minutes approximating brewing black tea. Then the plastics were analyzed.

This included limited examination of the impact of the brew on water fleas, widely used in ecological studies, and while this did not kill them, it measurably affected their anatomy and behavior.

What the study is not

One muddling aspect of discussions of the study is that they often treat it as one on tea. There are too many references to the plastic being higher than for “other foods.” That is nonsense simply because there was no tea anywhere in the research, except to confirm that it was plastic-free.

If instead of tea, the bags were filled with your favorite water-soluble fiber supplement that you value as a wellness aid, if they go through the exact same sequence you’ll come up with the exact same billions of particles figure. That’s important both in making assessments about tea in relation to other foods and beverages but also because the tea and fiber are what they are – outside your influence – but the type of tea bag or use of bagless loose leaf tea is a choice.

The choice is expanding and it’s very different from what many commentators on the McGill findings imply. They identify a villain: “silky” tea bags. These are high-end luxury packaging, often in pyramidal form. They are designed to release the flavor of whole leaf tea which is blocked by standard bags by lack of space to breathe and expand. A constant statement is that these bags, predominantly made of PET and nylon plastic, are growing in use: “Some tea companies are replacing traditional paper tea bags with plastic ones.” No, they are not. “There’s a new trend in tea… in with the pyramid-shaped mesh bag… most often plastic.” Not true. The trend is entirely in the opposite direction. The priority is to make fully biodegradable tea bags, a goal that has been achieved and is core to product and market development across the tea industry.Every major brand and company is moving to eliminate plastic. Tea bags are now made from corn starch, paper fiber, PLA (polylactic acid), organic cotton and abaca, a banana-derived fiber.

Stuart Nixon, v.p. Beverage & Casing Business at Ahlstrom-Munksjö, a major manufacturer of tea bags, explains that the heat-seal material in its BioWeb filters is PLA instead of polypropylene or polyethylene. “As part of the company’s testing regime, extracts are tested for safety compliance. Any dry matter within the extract has been tested and the results show that substances which might endanger health as well as any deviations from the materials stated composition, which are detectable by this method, were not found,” he writes.

Nixon said that “although traditional heat-sealable, ‘string & tag’ and BioWeb materials were not part of this micro-plastic study, Ahlstrom-Munksjö will in the coming weeks investigate if there is any release of micro-plastic particles from traditional heat-sealable, string and tag type and BioWeb filter materials that it produces.”

The McGill focus was on one of the choices: plastic tea bags. It reinforces the fact that they are a lousy choice. There is no longer a single reason to pick them out, in terms of quality of the tea, convenience, flavor, and other pleasures and merits of tea. The study suggests strong reasons to avoid it because the particles’ issues hide many unknowns that may merit alarms or indifference but why take the risk?

The best response: just say No

There’s a compelling reason to avoid plastic in your tea choices that dominates everything else. It is one of the most serious, even horrendous, global ecological problems through its growing accumulation in oceans, on beaches and in landfills. Individually, tea bags, plastic straws and bottles are a tiny contributor but they add up to an increase of millions of units per minute, of which at least 10% will add to oceanic garbage dumps.

- Avoid plastic tea bags completely: you can check out where a brand stands in the move to biodegradable bags – if you really prefer bagged tea – by seeing what it highlights on its Web site. Look for the elite B Corporations that pass a thorough certification process for social contribution, of which environmentally safe packaging is a core factor.

- Make the entire McGill research topic go away. Drink loose-leaf tea. No plastic particles whether billions or mere thousands, no complexities of bag materials, natural biodegradation, compostability. And, in the opinion of many, much better tea.

This image captures the wider issue. It is a small part of the Pacific garbage dump, where plastic goes to drift and amass.