How the Acclaimed Tea District Calls for Innovation – and One Planter’s Bold Response

In tea, Darjeeling, with its verdant hills and rolling mist, has for long been associated with the pinnacle of a certain kind of British excellence. Located in northern Bengal, India, this legacy of British colonialism is home to some of the world’s finest leaves. Its bountiful environment, rich soil, and unique climate have raised arguably the world’s most outstanding tea harvests. It should follow then that business would be booming, with many ‘tea toasts’ in the offing to celebrate. Unfortunately, this isn’t the case – and hasn’t been so for some years. Competition from cheaper teas on the international market is pressurizing the industry prompting tea traders to adulterate pure Darjeeling with lesser variants. Aging plants are resulting in declining yields; flavor profiles are becoming less brilliant: Darjeeling tea’s ‘wow factor’ seems to be diminishing.

While some planters have dug in, blaming flavor issues on the weather, making the same traditional orthodox tea that has consistently been grown in the district, others are innovating to extract Darjeeling’s distinctive flavor from their plants while offering different tasting experiences akin to East Asia. Leading them is coder-turned-planter Rishi Saria, CEO of Gopaldhara and Rohini Tea Estate of Sona Pvt. Ltd. But he, too, draws from tradition – just a newer one.

Moonlight Tea

In 2011, when the famed UK-based retailer Harrods of London decided to expand their tea selection beyond the plentiful varieties of spring, summer, and autumn harvests (the flushes as they are known), they came to Goodricke’s renowned Castleton Tea Estate with a bold request: “Make us a tea with flavor like no others,” they demanded. “Something that we can sell as ultra-premium.”

Garden Manager Pranab Mukhia put a small team to work on this project: “We need a taste that’s sweet, more fruity than the first flush, and also crisper than the typical orthodox tea.” He directed the staff to “find me the right leaf in the right part of the garden, and we’ll put our best pluckers on it.”

His assistant, DB Gurung, who passed away in 2022 after serving Goodricke Tea Company for over 50 years, knew just the place and plant. Tea workers often pluck unused or neglected leaves from plants, dry them in the sun, and hand-roll them to brew a simple tea. In doing so, they become familiar with the variety of flavors that can be had from different parts of a given garden, more so than even the owners or managers. This was one such case – familiarity by necessity to drink ‘thé au naturel’ had uncovered a fantastic cultivar. Gurung knew precisely where to look, for no one was more familiar than the master tea blender with the qualities and character of the plantation.

Mukhia added a twist: after picking different combinations from various places, he gave specific plucking instructions so the tea would contain parts of the plant in a specific composition that other batches didn’t have. Not simply two leaves and a bud for this tea. (The exact formula is his trade secret.)

The very young leaves of the AV2 cultivar were silver with white down-covered buds similar in look and character to the white teas made in China. The leaves were hand-rolled to ensure no breakage.

After tasting the new tea, Harrods fell in love. “But we need a name for it,” they said. Mukhia gave them the name of the clone and part of the garden. They laughed. “Too technical…too boring!”

The day’s work had begun in the morning and ended in late evening with a full moon lighting the estate. “How about ‘Moonlight’?” Mukhia suggested. Yes…Moonlight – and that was it: the famed tea, copied now by other tea companies many times over, was born.

“Of course, there was more to it than that,” says Mukia. “The silver tips resembled the moon; it had a calming effect like the moon, and we felt enchanted after tasting it as though we were imbibing it. Then we remembered that, according to biodynamic farming principles, the moon’s gravitational force would likely have pulled the nutrients from stem to leaf, which could be responsible for its definitive flavor. After that, we decided that the plucking should be done around the time of a full moon to maximize this effect. All these factors contributed to the naming.”

In 2022 moonlight teas from Castleton sold for a record Rs 12,000 per kilo at the Kolkata Tea Auction and retailed for $1.40 a gram.

The Techie Innovator

A decade has passed since Mukhia used orthodox processing techniques to make moonlight teas. Innovator Rishi Saria prides himself in going well beyond tradition. Indeed, there appear to be few boundaries by which he permits his teas to be confined.

Saria’s gardens are a picture of incongruity: he operates both the low-elevation Rohini and high-altitude Gopaldhara, which produces some of the highest-elevation teas. The gardens bookend the Darjeeling district. Growing the leaf in two such contrasting habitats has advantages in that his experiments reveal how the leaf’s character can be brought out under different environmental conditions. He tends to produce orthodox teas from plants grown in Gopaldhara and oolongs, greens, and whites in Rohini, where post-plucking formulations tease out the inherent taste of the tea.

Like any other Darjeeling factory, when walking into Rohini and Gopaldhara, one is hit by an ethereal wall of heavenly aroma wafting through the air. Unlike other factories, his older rolling machines gather dust—the century-old Britannia machines are sparingly used. The only truly common and comparable physical feature in his factories (compared to others) are the long bays that contain unprocessed green leaves in which the foliage is spread out for drying – a process known as withering. Here, warm air is passed over the leaf surfaces and through the accumulation; it’s a technique that removes around 60 to 70% of the moisture from the leaves depending on the quality of the leaf and the type of tea one is trying to make.

In other smaller bays, leaves are doused with a fine spray mist, like Darjeeling’s own dewy haze. This controls oxidation in some leaves and hydrates others for making semi-fermented oolong or green teas.

The British had secretly brought Chinese workers to India (who faced their Emperor’s death threat for their sojourns). These workers revealed a method by which they processed tea by hand.

Related: A Remarkable Quest Reveals Untold Chapter in Tea History

Saria continues: “It has been over a hundred fifty years since the British brought Chinese tea to Darjeeling and over three-quarters of a century since they left, yet we Indians continue to process tea the same way the British did rather than learning from our fellow Asians.”

Saria is passionate about the process of making tea:

“For black tea, flavor changes take place, and if you’re only doing indoor withering, it normally takes between 15 and 16 hours from plucking till oxidation. That’s the minimum time for the required chemical changes to occur in the leaf to qualify as a good black or a medium oxidized Oolong. Then only that coveted Darjeeling flavor develops in the cup,” says Saria.

Saria’s tea repertoire is not limited to blacks and oolongs. He makes an Emerald Green Umami tea from the Japanese Yabukita cultivar, which has a clean, bright, and slightly sweet flavor; they also make a vegetal variety. Among whites, he does floral, honey fruity, citrus, spicy, woody in Bai Mudan, and Silver Needles combination. Among oolongs, he produces umami, spicy, honey, herbaceous, woody, and citrus oolongs – sometimes even getting creamy notes. Aside from the regular first, second, monsoon, and autumnal flushes, he renders spicy, honey black, plum, rosy, woody, roasted, and smoked blacks. Saria says that, unlike the burnt trend that threatens to ruin Darjeeling, his roasted blacks follow the Taiwanese traditional methods – slow roasting under low heat for a long – bringing out the natural sweetness in the plant, unlike how roasted garlic or onion caramelize to produce a sweet taste.

Gentle Processing

Saria believes that the natural flavor of the plant must be coaxed out of the tea leaves with a level of delicacy and care that is not achievable using cumbersome British technology. So, he turned tail on heavy rolling used in traditional tea processing to favor a gentler process.

“First of all, you are in Darjeeling,” says Saria. “…which is a cold belt – a mountain region. And the teas you want to make from here are supposed to be very delicate, fruity, and flowery. So, you don’t want something harsh, too astringent, requiring you to add condiments like milk or sugar. To do that – we realized that the tea plant has everything in it – it just needs to be preserved, prepared, and processed properly – sometimes that means a gentle approach,” explains Saria.

“What’s more is, I think there has been a change in the consumption pattern of tea. While a certain proportion of Darjeeling is still being consumed with milk and sugar, I want to make teas more delicate and easier to drink without adding condiments – to match changing consumer preferences,” he asserts.

“So rather than using the big 36- or 48-inch rollers that are still used in most gardens and haven’t changed since the time of the British, we brought in some machines that are much smaller and roll very delicately,” he explains.

Indeed, in addition to augmenting their technology with new imported machinery, Saria’s team has been busy developing their equipment under this former techie’s leadership.

“To aid oxidation, after doing much research on the internet and other sources and – and after conducting many trials – we have designed machines which oxidize the leaf without breaking the leaf into many pieces,” he says.

Breaking the leaf causes aroma loss and heavy liquor to develop; hence, the teas easily become too harsh too quickly. “So, our teas are very clean, very easy to drink. The flavor and fruity aroma that you get – and that flavor is prominent; you don’t have to search for it – it’s abundant,” Saria says with a smile. “Also, using the new smaller rollers, you get a lot of whole leaf. Whole leaf has its own charm as it can readily be brewed multiple times. The leaves brew slowly and are very suitable for the Gaiwan brewing style (a Chinese technique in which flavors are coaxed from the leaves in multiple short steeps). We have spent a lot of time, energy, and effort on that, and you can say that we have now reached a level of comfort in this style of tea making, and we’re proud of this achievement.”

Another achievement in the making at Gopaldhara and Rohini Estates is the degree to which Saria is planning for the future. Recognizing that the advanced age of many plants in Darjeeling is a problem, Saria has been replanting much more than any other tea company director.

However, replenishment is no simple task. The plants must be prepared in tubes and raised to the point where they are substantial enough to be planted in the gardens. This is done in the winter. They are covered and wrapped to survive the harsh conditions of Darjeeling winter. Plants that survive their first winter tend to be viable in the long run.

“Depending on the elevation, the transplanted bushes can be viable as early as seven years,” says Saria.

What is the scale of their replanting operations? “Next year, in winter, we’ll prepare another lac plants (100,000) for replanting,” he says. When I asked a manager of a famous garden the same question, he had a vague answer: if they got time, they would strip away unviable bushes and replant them – a far cry from Saria’s planned, systematic approach.

Some planters are against replanting. They point to the ancient tea plants harvested in China that are still producing sweet teas after hundreds of years — evidence that plants can be viable for far longer than conventionally thought. However, one must acknowledge that as yields decline with age, so too would flavor loss as smaller lots translate to less complexity and a more limited flavor profile.

A Change in Consumer Preference

“Until recently, Darjeeling never needed to make specialty teas,” Saria explains. “The tea itself was a specialty brand with its own distinctive flavor.”

Also, traditionally, customers came from the UK and then the Soviet Union, countries with tea drinkers who preferred heavily liquored, stronger brews, their consumption practices requiring the addition of condiments. Consequently, they were pretty happy with the broken leaf standard (BOP grades) from large British rollers that released heavy liquor into the tea. The rest of Europe had different ideas of how to consume tea, influenced by their colonial experiences in East Asia. Many Europeans view milk and sugar as undesirable distractions from their enjoyment of tea.

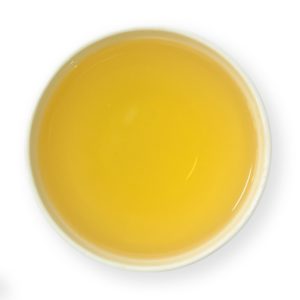

So, the ‘light and bright’ concept was born: a light brew with a golden liquor. This required exceptional leaf with high aromatic properties and some balance in the body of the tea resulting in a cup bolder than aromatic water. The Darjeeling of the ’90s and early 2000s had this inherent flavor during the spring harvest, but retaining these properties beyond First Flush became difficult.

The old British machines being attuned to making faster liquoring tea didn’t help. “There is no way you can make oolong with this or take multiple brews with this type of leaf,” says Saria. “I feel that mountain tea should not have been made this way. In my opinion, teas from Darjeeling should be smoother, more exquisite to drink on their own, and more oolong in character than black. So that is why we have made the adjustments in our equipment.”

“I took my cues from the mountain areas of China and Taiwan where black tea is consumed without milk and sugar, and the flavor stands on its own,” Saria asserts. “Why else make mountain tea? Good milk tea can be found in Assam, Sri Lanka, Kenya, and elsewhere. It makes no sense, in my opinion, to make premium mountain tea that requires milk and sugar.”

Saria’s new equipment crushes but doesn’t break the leaves in the rolling and pre-firing phases of processing to extract maximum flavor without any loss in leaf grade. His in-house mechanical innovations are now being copied at other factories. So too, is the use of Chinese equipment never seen at Darjeeling Gardens.

Is Saria worried about others replicating his new processes? “Oh no,” he says. “I’m very open because I feel strongly that this is the direction that the whole of Darjeeling needs to go.”

Excellent and informative writing. Waiting for the book about Darjeeling tea Garden.

This was such an enjoyable and informative article of Rishi Saria’s tea estates and processing techiniques. I have been buying teas for some time now from Golpaldhara and Rohini .

Saria’s presence on Instagram to advertise his teas has continued to delight my senses. A job well done!

I am so happy to see such deviate innovation.

Mr. Rishi, what’s the weather that roasting day? How long it rest for 2nd roasting? It is these details hooked me. Last autumn the drought was so deadly, the fresh leaves were like hollow patients, but you can not just dumped them right?! I had to became a doctor to recover it while tossing it, to get the balance of Yin and Yang. Last week, the leaves were bitten by insects, no way to make traditional tea, instead I combined White tea and Black tea craft, as well as Taiwan Oriental Beauty craft, finally made a shinning monster. Mr. Rishi, if one day we sit together, I would like to talk about the bad of the tea you and I made, instead of the good ^_^

Gopaldhara and Rohini has created some exceptional benchmark in the world of Darjeeling teas. I would agree that there is so much to experiment in tea, apart from the traditional styles of making orthodox teas (both in Assam and Darjeeling)

So much to learn from Shiv Saria and Rishi Saria 🙏

Dear Rishi.

I am very, impressed with your deep interest and knowledge of Tea growing and processing. Of course, your family is doing wonders.

I have little idea on these but it is interesting to know all this.

All the very Best in your committed endeavours.

Thanks for this very enjoyable article which provides a sigh of relief that there is someone creatively exploring to bring back the elite position of Darjeeling Tea, especially the aromatic golden cups variety, on the world map. I wish the industry associations and government agencies come together to contribute to this effort in retaining the characteristics of the unique Darjeeling terroir and crafting new processing techniques, to create many more “Moonlight” type teas with unique flavours. I wish Gopaldhara Tea much success in this endeavour.

Nice writing. Very well described.

May I have online issue of ‘Black tea from the green tea plant’ ?