Anthropologist Sarah Besky offers a fascinating view of the Indian tea industry through the significantly relevant yet frustratingly intangible factor of ‘quality’.

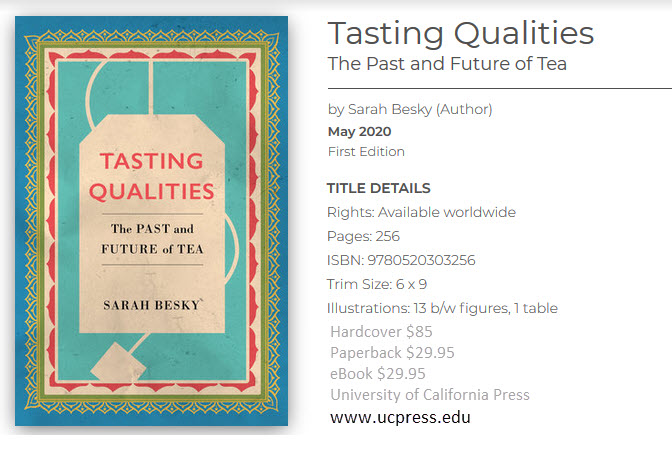

Her new book, Tasting Qualities: The Past and the Future of Tea, manages to easily deconstruct and demystify the space between the plantation and the cup of tea, by introducing every stakeholder from brokers and auctioneers to scientists, blenders, wholesalers, and the retail market – while elaborating on their role in creating, standardizing, and ensuring quality. Rightly so, because tea quality is the one constant along every step of the tea supply chain.

Besky also uses quality as the vehicle to examine the great divide between India’s orthodox and CTC production. She demonstrates there is no better way to align these disparate worlds than by bringing them into a single conversation on quality. Having said that, this book is not about CTC vs orthodox teas.

Besky also uses quality as the vehicle to examine the great divide between India’s orthodox and CTC production. She demonstrates there is no better way to align these disparate worlds than by bringing them into a single conversation on quality. Having said that, this book is not about CTC vs orthodox teas.

Tasting Qualities is presented in six chapters, bookended by an introduction (“The Production of Quality”) and a conclusion (“The Endurance of Quality”), which stand by themselves as interesting essays.

Besky questions the role of quality in contemporary capitalism. In response, she offers a historical and contextual understanding of the perception of quality by the various stakeholders, and therefore, their influence on the value ascribed to tea.

Chapter 1 focuses on the tea brokers of Kolkata, who she describes as all-male “main arbiters of tea quality”. The tea brokers are a remarkable group and Besky offers a comprehensive view of the functions and responsibilities hoisted on them. Even as she writes about how brokers assign value and therefore quality markings to tea, Besky nudges the reader until you can’t ignore it, that tea broking is still a male bastion, an “old boy” network.

The second chapter extends from where the brokers finish their role, into the auction rooms. It’s full of vivid descriptions; I’d go so far as to say that there seems to be a great desire to recreate in minuscule detail the setting and the scenario (lunch menu, wood paneling, photos on the wall, etc.). Where they work best is in bringing alive the theatre of the outcry auction, especially given that auctions have since gone digital. As an Indian reader, I find that her description of order within a chaotic setting may surprise a Western audience, but is quite a familiar notion, and not at all surprising in the results it’s able to produce.

The middle of the book takes up with blenders and tea scientists. These chapters are quite entangled in the history of Indian tea, Indian independence, tea research, and the establishment of the Tocklai Tea Research Institute in India. Against these dramatic changes, Besky unravels the science that has formed the backbone for tea quality.

The narrative relaxes by Chapter 5, “The Quality of Cheap Tea”. Here, Besky explores the relatively recent creation of CTC tea and how the Indian market embraced it. Setting it in the home of the CTC tea, the Dooars, she seamlessly brings into the conversation agrarian practices, migrant and marginalized workers, sick plantations, small tea growers, and bought-leaf factories. By referencing quality periodically, she allows it to reign in the conversation expertly. This was by far, my favorite chapter, and by itself, does a lot to convey a greater understanding of the CTC market, which otherwise suffers greatly from the false notion that as a less expensive alternative to whole leaf tea, Premium CTC is somehow inferior. In fact, a distinctive feature of black tea is the fullness and range of flavors that it can absorb and enhance.

The last chapter examines the quality of the market, where Besky cites a combination of historical research and present-day developments to raise the question of tea quality in a liberalized Indian market. The narrative returns to Calcutta auction. Outcry auctions have been disbanded and are unlikely to return. The author enjoys a front-row view to the first day of e-auctions and the undercurrents of change it carries. For the first time, and perhaps unintended, the author’s allegiance with the brokers comes through. She seems to temporarily set aside academic enquiry as she shows what has been lost with the rejection of the 300-year tradition. There is a method and choreography in the outcry auction that produced an outcome that cannot be replicated digitally. In this chapter, too, she fondly describes the brokers coming to terms with the changes, written with the camaraderie of one who is no longer an outsider.

Although Tasting Qualities is about the Indian tea industry, it remains geographically in the region of Kolkata, Siliguri, Darjeeling, and the Dooars with some mention of Assam; the south Indian tea industry is not included. But the omission, as it turns out, is yet another quirk of the industry. Besky offers an explanation: “Many of the reasons I focus on one part of India only have to do with the way that anthropologists tend to do research. I have long-term relationships in the regions in which I work. In my work in Darjeeling, I speak Nepali. In the Dooars, I also primarily use Nepali, but also some Hindi. In Kolkata at the tea auctions I used English. I also found when I was doing the historical research for the book that north India and south India emerged as nearly completely different industries. Sure, the auction infrastructure, for example, was similar. And certainly, the plantation is a contiguity. But what is striking is how, in terms of promotion and regulation, a cavernous line in the sand, so to speak, was drawn between the two.”

The aim of the book, as the author says, is to use quality to provoke the reader to ask why things are like they are and what keeps them that way. To achieve this, she manages to distill a century’s worth of tea history and more than a decade of tea research, and connects isolated events and developments. The result is a new perspective to the Indian tea story that “brings together materials and ideas, tastes and feelings, chemistry and climate change.”

Tea Market

Get More Value from Your Tea: BRU Maker One

+41794574278

Jacque's Organics

(647) 804-7263

I will read it as tea is my lifeline

Around the time of her book release there was an editorial Sarah Besky had written, I happened to read – published on the new International Tea Day this May.

My two cents for Sarah’s perspective (or lack of): there is always two sides to the coin – flipping it is important to get the whole picture!