Tea and Buddhism: Much More than Just Contemplation

It seems natural to associate Buddhism with tea. Tea expresses China’s history. It symbolizes the ethos and practices of yoga, Zen and meditation. Buddhism’s concerns for healthy daily living conjure up images evocative of tea. They highlight its calming, cleansing, contemplative, and ceremonial nature. These never even hint at caffeine.

Somehow, the link doesn’t quite seem the same for other beverages. Seek kharma with a langorous double latte jolt, a contemplative double rye on the rocks. Buddhist tequila shots?

But the association goes much further. Buddhism shaped almost every core element of tea production and much of its social context. Many of its millennia-old practices still define China tea. These encompass its 80 million smallholder family tea farms and location of the most prestigious growing areas. They define many of its tea worker communities. They explain its near absence of national tea brands.

The two core traditions of tea

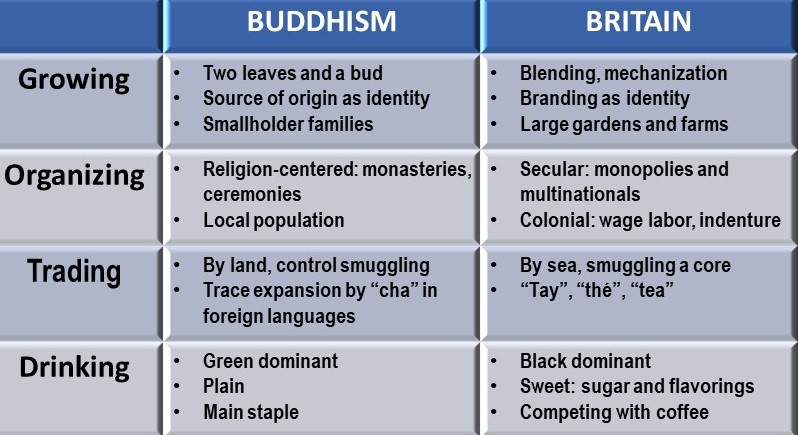

There are two great cultures of tea: Buddhist and British. (The latter is too often described as English. Many of its most outstanding innovators were Scots.) Though they converge in the modern global economy, they differ in evolution:

Buddhism drove the methods for producing great tea. Britain sold it. It led its democratization and consumer industry-creation. Buddhism expanded tea along the Silk and Horse Tea Road. Britain built on the Portuguese and Dutch lead to make the Pacific its cash flow. Buddhism created the rituals and ceremonies of tea and Britain its social etiquettes.

Same bush, leaf: different names, trade paths

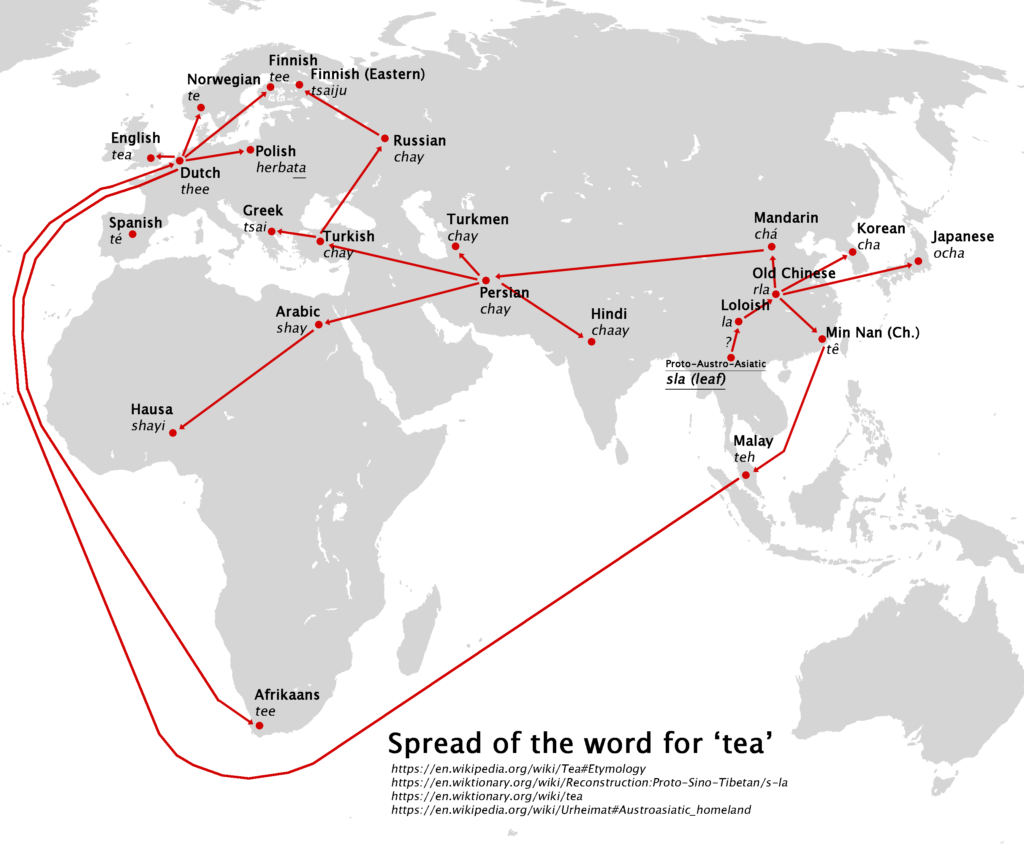

The dual traditions are captured in the two root words for tea, both of which originated from dialects of old Chinese. “Cha” was the Mandarin term. It tracks the landward expansion to Persia (Iran), India, Russia, and across the Arabian Peninsula and Africa. Buddhism brought cha to Japan and Korea via the only sea routes China navigated.

The Dutch traders who were integrally part of the English/British tea evolution docked in Amoy (modern Xiamen, in Fujian Province). Here, the local dialect used te “té.” Ships carried te, teh, thee and tea along the 20,000 kilometer seaways. Horses and porters took cha along the 4,000 kilometer Tea Horse Road.

Source: https://moverdb.com/tea-coffee/

Source: https://moverdb.com/tea-coffee/

One intriguing footnote to this linguistic journey is that the trade routes converged at their northernmost point in Finland. There, the eastern region today uses a variant on cha – “tsaiju” – and the main areas “tee.”

Buddhism’s land farmers defined and refined every element of tea making, from the bush to the cup. British traders took their product and began to change it. They built new blending skills to achieve consistent levels of quality. Importers shifted from green to black tea to avoid deterioration of their cargo on the six month sea voyage. Once Scots had broken the China monopoly, British growers in India and then Ceylon moved to larger scale farming. They adopted mechanization. Auctions coordinated distribution. Merchandisers moved to make their names the brand, not the tea.

China turned inward as British Imperial colonialism took trade away from the Chinese Empire. Its tea cultures in 1990 were very much the same as 1690 and even 1290. Buddhism was the link across green tea makers in China, Japan, Korea, Formosa (now Taiwan), Indonesia, and Vietnam. It defined identity: ethnic, historical, community, and religion.

This image captures the dominance of Buddhism identity over geography and nationality. It is a celebration day in one of the world’s greatest tea growing regions.

It’s not Tibet or China, but Darjeeling in India.The Indian population is predominantly Hindu and Muslim. Buddhists amount to fewer than 1%, In Darjeeling city, the 2011 census shows it as 24%. This reflects the immigrants brought in to work in the tea gardens from Tibet, Nepal, and Sikkim. Ceylon tea is strongly associated with British colonialism and is a core of “English” teas, along with Hindu Assam and Christian Kenya. It’s 70% Buddhist.

In all these very diverse countries, where there’s tea, there are temples.

Cameron Highlands, Malaysia

Buddhism: agronomists, itinerants, and artisans

Tea drinking became part of the daily routines in temples during the Tang dynasty, around twelve hundred years ago. By then, Buddhist monks had made tea a mature farming sector. They located their monasteries on the high mountain slopes that provided the ideal climate and terrain for tea growing. Farmer-priests formalized practices and disseminated powerful information and guidebooks. Monks shaped the ceremonies and accoutrements of cups, pots and tea preparation. Today, they would be termed agronomists: scientists experts in soil management, crop production and irrigation.

The best-selling and for centuries definitive book, Cha Ching (The Classic of Tea), by, of course, a Buddhist monk, was published around 720 AD. It is a comprehensive and sophisticated guide to soil, harvesting, processing and utensils. The 55-page “Classic of Tea” even specifies the height to hold the pot to pour water into the cup.

The monasteries and temples were social businesses. As they expanded in location, size and impact, they spread tea to the masses. The tradition of wandering monks spread tea growing to Japan and Korea. The monasteries developed pan-frying as an alternative to steaming in making tea. Religious leaders formalized the ceremony and ritual that became a core to upper class social norms. Temples introduced bamboo tree-shading. These elite farms produced the superior teas that attracted the attention of the royal court – and funding.

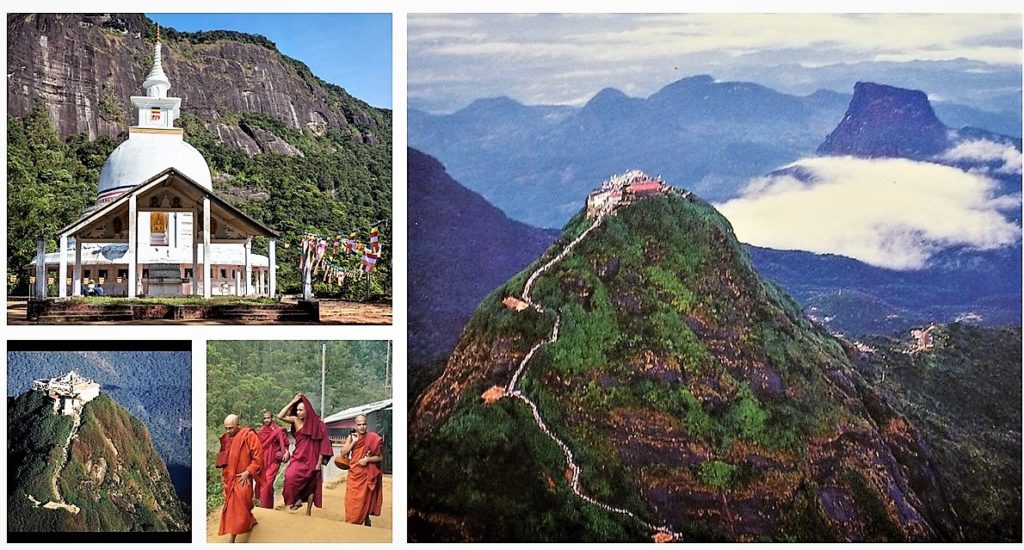

Many of the major tea regions retained Buddhism at the core of their communities. These formed round the temples located up in their hills. Perhaps the most outstanding illustration is Adam’s Peak, in Sri Lanka. The temple is ecumenical and more than somewhat remote. It produces one of the most superb whites in the world. The mountaintop is an ideal terrain for tea growing. But the tea is there only because of the temple. There is no way any farmer would single it out.

Temple teas

There are other Buddhist-created teas that have maintained a continuous reputation for over a thusand years. All this was despite the invasions, civil wars, famines and rebellions that mark Chinese history. Mongol invasions unraveled the social fabric of tea tribute, ritual and Imperial gardens. The Artisan craft was self-sustaining.

One noted example is Big Red Robe (Da Hong Pao), the famously expensive and sublime oolong. This sold for as much as $35,000 for an ounce in 1988. It still commands absurd prices for leaf perfectly picked at the right instant with the right clouds overhead, etc.

Pi Lo Chun, Green Snail Spring, is a long-established temple tea. It is now grown in other provinces and in Taiwan. Wuyi rock tea, the source of so many great oolongs, developed as small farmers moved to the monastery areas. This followed an Imperial edict requiring all tea be leaf not brick. They created new techniques that are among the most complex and produce some of the best oolongs in the world.

The temples of China had become refugee centers. Peasants fled the devastation of their lands. They hid to avoid being forced into serving as battle fodder for the marauding armies. The havens offered safety and sustenance. Increasingly, emperors and their officials gave temples taxing authority and granted them lands. They developed their own agricultural trade, handicrafts and medical services. In the fifth century BCE, the breakaway Northern Wei kingdom, today’s China north of the Yangtse river, contained 40,000 monasteries with 2 million monks and nuns.

Embedding tea in everyday routines

Buddhism was the very opposite of the sit-and-meditate stereotype. It was get-up-and-go energizing. The daily routines of the monks’ life aimed at combining physical labor and mental contemplation. Tea was the only non-alcoholic drink that mildly energized – the caffeine positive. It could be safely consumed all day. As it became more and more embedded in Buddhist philosophy, the pragmatic extended to the spiritual. Tea ceremonies were built around the tenets of respect, harmony, purity and peace. These infused the Noble Eightway Path.

The pragmatics were powerful in themselves. Tea offered the first alternative to alcohol. It also used little of the scarce farmland demanded for wine and beers. In England, around an eighth of the total land area went to growing wheat for bread and ale. Tea provided an alternative working class food that was imported, high in vitamins and minerals. China’s lowlands similarly were committed to rice-growing, with growing population pressures. Tea could be produced on the idle mountain slopes.

The temples’ encouragement, diffusion and professionalizing of tea growing countered one of the greatest killers in society: water. We have the notion that in whatever Good Old Days we weave nostalgic regrets for, water was so, so much purer. Uh, no. The fastest way to spread dysentery and cholera was from the water available to crowded clusters of populations.

China adopted the routine of drinking only boiled water long before tea became a drink. It was initially eaten as a herb or mixed with other ingredients as a paste or broth. Several of the myths of its origin as beverage illustrate this. Emperor Shen Nong had ordered that all his subjects drink only boiled water. When he woke up one morning he saw a leaf fall from the tree into his bubbling pot. He was captivated by the totally new flavor it added. That was in 2737 BCE, coming up to five thousand years ago. A myth, obviously, but it is intriguing that it so directly relates tea to water.

An emerging body of research suggests this was a very key contribution of Buddhist tea growing. Historical mortality rates in the crowded cities from dysentery and typhoid seem much lower in major tea growing regions. There are correlations, too, between tea consumption and population growth and disease in Japan. In England water-related deaths rose in high tax and dropped in low tax periods which affected the affordability of tea.

It is an entertaining irony that tea was the safe alternative to the dangers of water.

The militant side of tea and Buddhism

Buddhism expanded from India, to China, Japan and across East Asia. This was not sages sitting in isolation in temples that were centers for learning and ceremony. It evolved as a socio-political movement. Many of its sects built substantial military capabilities.

In the times of war lords, these provided for shelter, protected farms and provided schooling. Over time, communal roots weakened. Tea became associated with the aristocracy and military. Ornate tea competitions were court events. The rituals that are associated with tea as pomp (and tea-talk as pomposity) became more and more rigid. The Imperial Court imposed cruel burdens on entire communities to produce luxury “tribute” teas. One of these was the pumpkin size brick puer tea known as “Hunan-heads.” They were a reference to the severed human heads that were ritually also presented in tribute to the Emperor.

In Japan, tea and Buddhism together became identified with the ethos of the samurai. Monks were routinely “military advisers” attached to clans in their battle campaigns. Here’s an extract from the obituary of a famed general. “He defended the castle of Kishiwada and personally took 208 heads. He was also a noted tea master.”

Buddhists on duty, at tea; samurai 1600s

Buddhists on duty, at tea; samurai 1600s

One of the most intriguing economic and military developments was the massive trade with Nepal. This was the powerful Buddhist kingdom of the high plateaus of what are now India, Sikkim and Tibet. The core weakness of China was its lack of horses. Those were both abundant in these territories and the advantage of the ever-invading barbarian hordes. There were plenty of them: Scythian, Mongol and tribes of many syllable names.

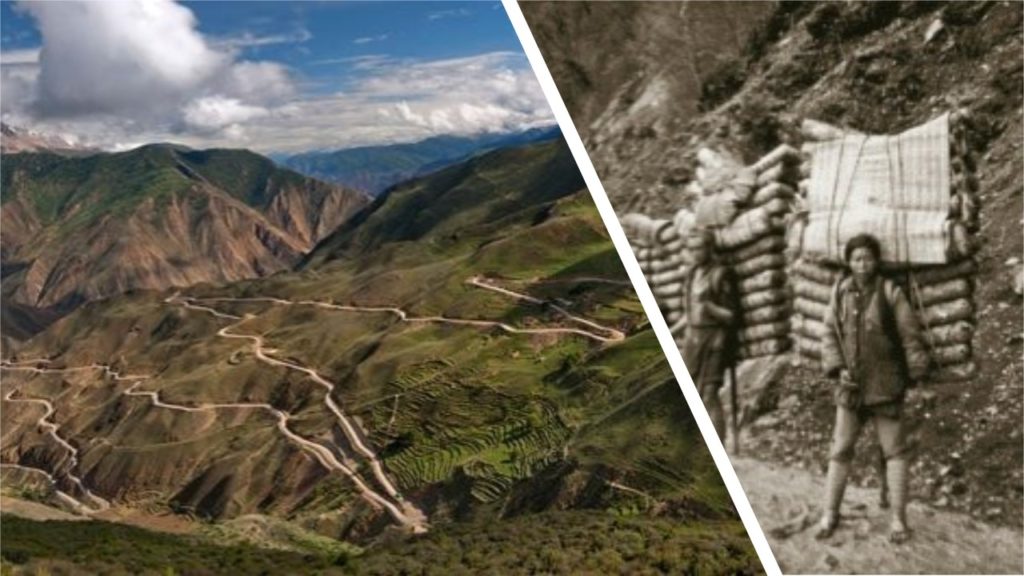

The still-traveled Tea Horse Road runs 3,000 mountainous miles from Yunnan to Bengal, Sichuan, Tibet, and Burma. It is somewhat winding.

Religious Buddhism, secular British colonialism

To some degree, the contrast between the Buddhist and later world of tea is the spiritual and pragmatic versus the social and commercial. Religion was never part of the British tea tradition. It was central to that of China and Japan. In both instances, the organization, education and expansion of Buddhism added a lasting practicality.

There is some parallel with the role of Catholicism with alcoholic beverage. The genius of Dom Perignon turned the mediocre sparkling wines of England into French national identity. The monks of Corsedonk still make and sell Belgium beers that could bring a horse to its knees. Benedictine, Chambord and other exotic cordials, all named for abbeys and orders. The monks of both Eastern and Western faiths made very good drinks, were innovators and shaped their wider society.

Past heritage, future innovation

Of course, the timelines of history have converged. The strength of the Buddhist tea tradition is also its weakness: localization. Today, very little of the best tea of Japan, Taiwan and Japan is exported. It’s ironic that Lipton has three times the national branded tea market than the largest Chinese player. An article asks “Why is Lipton more powerful than 70,000 Chinese tea companies?” History.

The British tradition was built on exports. Every elite tea maker in the world is linked into the global supply chains. Interestingly, it is reaching limits that are moving many growers back into the pre-Sugar era. They are recognizing that the commoditization of tea as a bulk ingredient is increasingly a marginal business. “Premiumization” is the new goal. In Japan, Darjeeling, Taiwan, Indonesia and Japan,, small is becoming very beautiful. Darjeeling’s green and oolong teas, mediocre just a few years ago, are beginning to stand out in their distinctive styles.

Japan’s smallholders are setting the highest levels of productivity and its many localized senchas are exquisite. In Sri Lanka, the large farms are facing near-disaster in the drop in quality of the teas from their aging plant stock and depleted soil; official government studies show that it is the elite smallholders that are innovating and investing.

What is most striking in the Buddhist tradition’s history and legacy is just how much tea paced very basic elements of daily life: water, wakefulness and productivity, nutrition for the poor, rural income earning, and social conventions. Too often, tea marketing emphasizes the luxury, snobbery, elegance and special event aspects of tea. In the end, though, its centrality is the simple enjoyment of everyday life. The elegance is an addition, as is the spirituality.

One of the joys of tea is its near unbounded variety. Much of the commoditization of tea fueled by the British narrowed that variety and standardized the mass market. Premiumization is moving in the opposite direction. One example is that matcha is no longer a specialty exotic. It’s very much cool, trendy and popular with millennials wooed as the “new generation” of tea drinkers. White teas of exquisite quality are as easy to find now online as English Breakfast blends. Distribution of China’s and Japan’s elite teas remains fragmented. Most of the best is never exported. But if you want a Temple tea, it’s online. There’s a new convergence in the core traditions. Buddhism + British.

Tea Market

Get More Value from Your Tea: BRU Maker One

+41794574278

Jacque's Organics

(647) 804-7263

Peter,

Nice article, but Lu Yu, the author of the Chajing, was most certainly not a Buddhist monk.

Another clarification about the Chajing: It was published in its final form in 780 CE, not 720 CE. Lu Yu was born circa 733 CE.