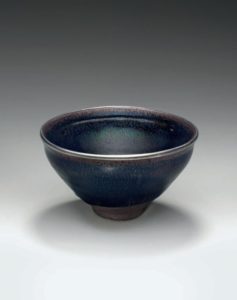

Jian Zhan teaware inspires poetic praise among its ardent lovers and devotees. Over the centuries, these unique teacups were called “the sacred vessel of tea”, the “king of teaware” and the “vessel born for tea.”

Tea Buyer’s Guide

- Reading the Leaves

- Preserving the Life of the Leaves

- Chigusa: Ancient Japanese Diaries as an Art of Tea

Those who gain a genuine appreciation of Jian Zhan teaware find it impossible to shed their fascination with the history, science, art, and economics of these enchanting tea bowls.

Dark Art

Black porcelain is one of the eight famous porcelains perfected during the Song dynasty (960-1279). Techniques to produce black enamel were discovered in the Later Tang dynasty (923-936). Jian Zhan’s heyday was during the Song dynasty. It disappeared in the late Yuan and early Ming dynasties during the mid-14th century.

Black porcelain was manufactured mainly in Fujian province where archaeological excavations have revealed the relics of more than black porcelain kiln sites. Kilns in those days were long, narrow, dragon-shaped ovens up to 150 meters in length that would wind up the sides of hills. Called dragon kilns, they were different from earlier ceramic ovens built from the floor up. In dragon kilns, flames traveled horizontally instead of vertically.

The earliest black porcelain kilns in Fujian were in the Shui Ji village in Jian Yang county, not far from the UNESCO world heritage-listed tea mountains of Wuyi Shan – the birthplace of red tea (known as black tea in the West) and oolong tea. Shui Ji is the site of the longest dragon kiln in the world. When operating tens of thousands of cups were fired at one time. Not only was this kiln used for making black porcelain, but it was also later used for making blue and white porcelain, evidenced by hand-painted broken pieces strewn around the kiln site.

The Significance of the Song

Arguably, Jian Zhan teacups were not as beautiful as other cups produced during the Song dynasty. So why their popularity? Scholars say that the design of Jian Zhan teacups cannot be examined separately from the social-cultural context of the time. In the Song dynasty, Neo-Confucian philosophy and Zen thought had taken a strong foothold in society and influenced many facets of life, including visual aesthetics. Simplicity, nature, and harmony were the predominant aesthetic. The simplicity of the shape, the unobtrusive color of the glaze, and the profound artistic conception were in line with the cultural standards of the Song era.

The cups were also suited to the functional needs of the time. Tea prepared during the Song dynasty was more akin to Japanese whisked matcha. The tea was known as Mo Cha (ground tea). The process of making tea was known as Dian Cha (literally translated as pour the tea). The steps involved grinding leaves, or bricks of pressed tea cakes, and sieving for the finest powder. The powdered tea was then placed in a pre-heated teacup. A little water was added and whisking turned the powder into a tea paste. Then, with great skill and attention, a long-necked Celedon pitcher was used to pour boiling water into the cup while the rapid movement of a bamboo whisk created a layer of cream-colored froth.

Frothing Powdered Tea in a Jian Zhan Cup

Dian Cha was refined into an art form during the Song era’s popular tea contests, first starting in Fujian’s Jian Zhou prefecture (the township of Jian Ou today) and later spreading across China. A marker of a good tea was a layer of froth that was long-lasting, snow-white in color, even in texture, and dense enough to bite the rim of the cup. Such qualities were easier to judge against a contrasting dark glaze which is why Jian Zhan became the cup of choice of the Song era – a good horse in need of a good saddle.

Jian Zhan’s First Trip Abroad

It is arguable that the Japanese have had a greater love affair with Jian Zhan teacups than the Chinese. During the Song dynasty, Japanese Buddhist monks traveled frequently to China to study Buddhist scriptures. Some settled in the temples of Mount Tian Mu of the Zhejiang province. There, Jian Zhan teaware was used for eating and drinking. These Japanese monks took cups back with them to Japan, naming them Tenmoku, a variation of the Chinese word Tian Mu, which means heaven’s eye. In time, the term Tenmoku referred to all cups exported from China to Japan.

Potters Experimented with Many Glazes

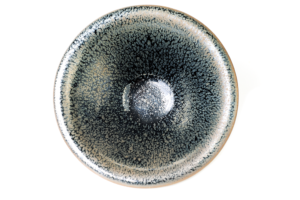

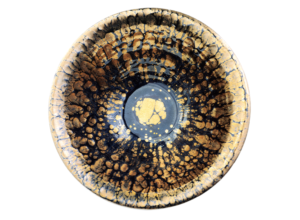

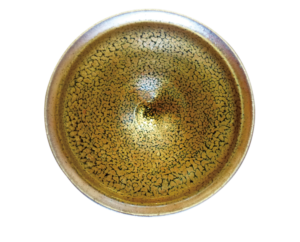

The first-rate patterns of Jian Zhan cups that were hardest to achieve were rabbit fur, speckled partridge feather, and oil spot. Less valued Jian Zhan designs, lacking contrasting patterns, were easier to make. These included black gold, red persimmon, and green tea leaf powder.

Examples of Jian Zhan glazes

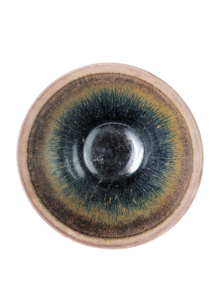

The Rarest Cup of All

Yao Bian cups (which, in Chinese, can be translated as Luminous Transformation or, in Japanese, translated as The Universe in a Cup) are the rarest Jian Zhan cups from the Song dynasty, with only four intact cups in existence. Three of the first known cups are locked away in museums in Japan – designated as national treasures – never allowed to be filmed, only photographed.

In 2009, broken pieces of a fourth Yao Bian cup were unearthed in Hangzhou, China.

They are stunning pieces of art – randomly dispersed oil spots against a black backdrop surrounded by halos of iridescent cobalt blues and emerald greens, resembling lunar eclipses by the ocean late at night. The mystery around its inconceivable formation has inspired many potters to devote their lives to replicating these cups. It is claimed that no one has yet succeeded, yet there are a number of Chinese and Japanese potters who have produced cups that are very, very similar in appearance to the original Yao Bian cups. The average price for one of these cups is US$13,000.

Materials and Methods

The Jian area of Fujian is rich in clays, soils, and rocks able to withstand the high temperatures required in making Jian Zhan wares. These include Shui Ji Southern Mountain Yellow Soil (clay loess containing 7%-10% iron oxide), Hou Ji Village Red Soil (laterite), Da Li Village High-Temperature Soil (kaolin clay) and Jian Yang Southern Forest Glaze Mineral (red iron oxide).

The raw glaze contains quartz and feldspar (which creates the glass-like component of the fired glaze) and iron oxide (which forms the patterns and colors in the fired glaze, ranging from yellow, gray-brown, dark brown, green-blue and black). Plant ash, containing calcium, magnesium, and phosphoric acid, is added for the flux (a metallurgy term for lowering the melting point of glass constituents that aid with the fusion of the glaze).

Three types of kilns can be used to make Jian Zhan wares: wood-fired kilns, electric kilns, and gas kilns. The first two types of kilns are the most commonly used. Temperature is easier to control in an electric kiln than in a wood-fired kiln. Yet internal temperatures of an electric kiln are still not perfectly uniform due to variables such as external temperature, so there are still defective and substandard results. This is why higher-yielding electric kilns are preferred. Where sentimentality for craftsmanship is in play, wood-fired kilns are preferred. However, cups made in wood-fired kilns don’t come cheap, as there is less than a 5% success rate.

It is a sobering sight to behold when you lay witness to a mountain of Jian Zhan cups smashed to pieces by their makers for only the slightest of defects. There must be many imaginative ways to repurpose the unwanted teacups, such as turning them into pots for Bonsai trees, perhaps. But Jian Zhan connoisseurs are adamant that substandard cups must be destroyed in order to protect the reputation of the cups and the industry.

When the slip-glazed cups begin their journey in the kiln, they are heated over several days, reaching a peak temperature of between 1280 and 1330 degrees Celsius. At these temperatures, the glaze layer flows downwards. At the lower peak temperature range, the glaze drags excess saturated iron along with it, creating streak patterns. At the higher peak temperature range, excess saturated iron separates from the glaze as air bubbles creating a distinctive circular pattern.

When the air bubbles rise and burst, it deposits iron spot patterns on the surface. Then, after cooling in a reductive atmosphere (meaning that the oxygen level is reduced inside the kiln, normally brought about by adding to the kiln fire 20-plus-year-old Masons pinewood resin), small hematite crystals are separated from these iron streaks and spots, helping to create the final three-dimensional markings on the surface of the glass layer behind them.

What can go wrong?

Many things can go wrong in the process:

- If the sides of the clay cup are too thin, the kiln’s high temperatures deform the symmetrical shape.

- If the kiln does not reach the required peak temperature, no markings will appear in the glaze.

- If the glaze is applied too thinly, the crystallization on the glaze will not be smooth.

- If the glaze is applied too thickly, the crystallization will not be visible in the glaze.

- If the reductive atmosphere is not right due to too much oxygen, second-rate glazes will result, as with red persimmon cups.

- A slow rate of heating followed by temperatures that peak for too long causes the glaze to drip.

- If a cup cools too quickly, the risk of breakage is high.

Extinction and Revival

It is a mistaken belief held among many who are unfamiliar with the history of Jian Zhan wares that the craft continued ceaselessly to modern times, passed down through the generations. In fact, Jian Zhan became extinct after the Song Dynasty.

When Emperor Zhu Yuan Zhang of the Ming dynasty advocated a policy of thrift due to leaner times, the production of Jian Zhan wares (which required a lot of manpower and natural resources) was gradually replaced with higher-yielding porcelain wares. In fact it has been speculated that the likely reason why the Yao Bian cup unearthed in Hangzhou in 2009 was in a broken state was because the emperor ordered it to be smashed.

After this time, the art of making Jian Zhan cups was lost until 1979 when China’s Central Academy of Arts and Crafts, the Fujian Provincial Commission of Science and Technology and the Fujian Provincial Institute of Light Industry formed a joint research team to carry out experiments in reproducing a rabbit fur cup based on scientific analysis of ancient relics. In 1981, the first imitation of an ancient rabbit fur cup was released, and from there, a market in Jian Zhan wares began to grow again.

Assessing the value of a Jian Zhan cup

The typical price range of modern Jian Zhan tea cups can be as low as a few dollars up to hundreds of dollars. The value is dependent on the rarity of the glaze pattern, whether the cup is handmade or machine-made, whether it is wood-fired or electric-fired, and whether it is made by a famous potter.

As for the value of ancient Jian Zhan cups, in recent years, auction prices have been so high that they have been grabbing the attention of the mainstream international media. In 2016, Christie’s in New York set a new world auction record for a Song dynasty Jian Zhan tea cup, selling at US$11.7 million.

A general guide to assessing the worth of a cup includes the following:

- Unadulterated (natural) glazes are more valuable than adulterated (artificially manipulated) glazes.

- Silver colors are preferred over bronze colors, particularly silvers with a blue tint, as they are apparently harder to obtain.

- Glaze markings should have a three-dimensional quality.

- There should be few-to-no secondary patterns on the glaze (so only stripes or only spots), as this is harder to achieve.

- The patterns on the glaze should seem ordered and symmetrical and go up to the rim as much as possible.

- The large spot at the bottom of the cup should be round, neat and symmetrical, and either unblemished, containing an opal halo ring or some other interesting pattern.

- For oil spot and rabbit fur cups, each spot or line should be singular, not overlapping with other spots or blending into different stripes.

- The outside edge of the glaze should be flat, not bulky, as well as symmetrical in shape.

- The texture of the glaze should have no defects, so no pinprick marks, blisters, cracks, or over-extended teardrops. (Note that teardrops that don’t overextend are prized by some collectors.)

- The feeling and weight of a cup in your hands also contribute to the aesthetics. You want to get a comforting feel from holding a cup (although this is entirely subjective).

What about these new fancy colors and patterns?

In the last few years, there has been an extraordinary increase in new glazes under the Jian Zhan name. These include cherry blossom cups, fire phoenix cups, and moonlight flower cups, as well as new colors in traditional patterned Jian Zhan cups, such as gold, aqua greens, and violets. These new styles are usually a result of either second glazes being fired over the first layer of glaze, or adding extra ingredients to the first glaze (although some makers will deny the latter). Purists do not count these new styles as genuine Jian Zhan cups, but there seems to be an extraordinary demand for such new styles since the range on the market increases with each year. This is likely helped by China’s e-commerce websites, such as Tao Bao, and video sharing apps, such as Tik Tok, which shine a bright spotlight on Jian Zhan wares.

Spurious claims

There have been many extraordinary claims made about Jian Zhan cups, including:

- pores in the glaze can absorb the minerals of hard water, thereby making the teas taste sweeter;

- long term use of Jian Zhan cups can prevent and treat anemia and hypertension, and balance the endocrine system due to iron ions in the glaze being absorbed into the tea liquors.

Unfortunately, there are no scientific studies that back up health claims or claims of improved taste. No marketing gimmicks are required – the beauty, uniqueness and historical significance of Jian Zhan cups is sufficient for a tea drinker to want to possess their own special Jian Zhan cup.

The End has led to a New Beginning

Knowing the extreme difficulty in controlling the final creation of a Jian Zhan teacup leaves one with a deep respect for each precious bowl. Once your interest is piqued, you will likely commence a winding and fascinating journey into the customs, philosophies, and teas that can be found in China’s Fujian province.

If you truly desire to possess your own unique Jian Zhan teacup… consider traveling to where it all began and let the teacup choose you.

—

Editor’s Note: I know that you enjoyed this article, so please share it with your friends on social media.

Free Trial Link | www.teajourney.pub/3 | Thanks, Dan Bolton

Tea Market

Get More Value from Your Tea: BRU Maker One

+41794574278

Jacque's Organics

(647) 804-7263

Any recommendations on where to find artisan Jian Zhan pieces for someone who lives in America? There appear to be very few places selling work by craft masters and other skilled artisans online. With the pandemic, I don’t see myself getting to China for a buying trip any time soon.

Hi Matthew. Sorry for the late reply. I can help you with a purchase if you like, once I get back to China.