Photos by Qiu, courtesy of Cha Dao Life Magazine

Photos by Qiu, courtesy of Cha Dao Life Magazine

Retold by Si Chen

With its striking look, Thousand-Tael tea stands out of the post-fermented tea family. post-fermented tea, or dark tea (‘Héicha’), is a class of tea that has undergone microbial fermentation, from several months to many years. The tea is little known in the West for a couple of reasons: it has an unattractive look and the taste is acquired, but it is noted to have ample health benefits. The microbial family in post-fermented tea has been found through clinical studies to aid digestion, lower cholesterol and blood sugar level, and assist in weight control.

Post-fermented tea is one of the six basic types of tea that originated in China, both in its cultivation and production. The most famous post-fermented teas are Pu’er from Yunnan Province and the Anhua dark tea produced in Anhua County of Hunan Province in China.

Thousand-Tael tea (‘Qianliang’) is one of the most famous types of Anhua dark tea. It is produced in the traditional post-fermentation manner but is also quite an anomaly. It has a record-setting height of 156cm and an astonishing weight: each stick weighs 36.25 kilos and is 20cm in diameter, which equals to 1000 taels (an old weighing term).

Origin of Thousand-Tael tea

The origin of the Thousand-Tael Tea can be traced back to the first year of Daoguang in the Qing Dynasty (1820) as a result of friendly cooperation between Shaanxi merchants and Anhua tea makers. At that time, merchants from Shannxi province were selling Sichuan teas exclusively via the tea-horse route to Tibet and Central Asia. Due to a large demand, merchants started to source teas from adjacent tea producing regions and slowly found out that teas produced in Anhua county in Hunan province had better quality and a much cheaper price. Gradually, Anhua became an important starting point for the tea-horse road.

Unique bamboo lattice wrap

After the tea was purchased, the tea needed to be carried on the backs of horses. Anhua tea workers started the preparation by stuffing the loose teas into small cylindrical brick and packaging them with a bamboo lattice wrap for long haul travel. The lattice wrap is served as a two-way humidity adjuster for the enclosed tea brick: when it rained, the wrap absorbed the moisture and kept the tea dry; when it dried out, the wrap returned small amount of water to the tea to rejuvenate the teas’ microbial fermentation, acting similar to a watering bulb.

Thousand-Tael tea is also described as Flower-Rolling Tea (‘Huajuan’) because the lattice of bamboo wrapping leaves a weaving pattern on the surface of the tea, which is referred as ‘flower pattern’.

During Qing emperor Tongzhi’s reign, Shanxi Sanhegong Tea Firm started to produce “Thousand-Tael Tea”. Each package weighed 1ooo taels in old measurement (about 37 kilograms) and eventually the firm added more teas and packaged them with improved wrapping methods.

The production technology that is exclusive to Thousand-Tael Tea was originally kept by The Liu’s Family and followed the traditions of male succession and family inheritance. In 1952, a Tea Factory called Baishaxi (now it’s a brand) acquired these unique skills through employing Liu’s descendants. In June 2008, Thousand-Tael tea’s production skills have been recognized as a national intangible cultural heritage. Dark tea has enjoyed a good market for the past two years. Gross revenue used to be 20,000 – 30,000 yuan (US$3,000-4,500) year after year, but in 2014 it skyrocketed to a historical record: 200,000 yuan (US$30,000).

Production

Once considered confidential, the production technology of Thousand-Tael tea still remains one of the most complicated, and to some extent, enchanting tea making processes. Making Thousand-Tael tea involves heavy manual labor. Different Dark teas shares a similar process of crude tea making, involving withering, fixing, rolling, fermenting and drying. What is unique and spectacular about Thousand-Tael tea making is the following steps: steaming, stuffing, and tightening. With its primitive scroll look, Thousand-Tael tea is also the only kind of tea known to be produced alongside with packaging at the same time, rather than going through a packaging process when the product is ready. The product is ready at the same time as the packaging.

Steaming and Stuffing

Workers usually choose Grade 3 level of tea as raw material for Thousand-Tael tea. The premium grade is usually reserved in small quantities locally and would not be pressed into a cake or brick. After screening, sorting, and removing impurities, the crude tea will be steamed in a bucket under high temperatures. The steam softens the tea, which will later be transferred to a long cylindrical bamboo lattice basket that is either made on site or purchased.

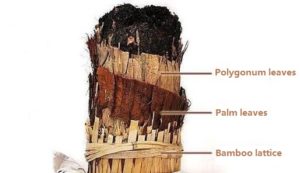

The bamboo lattice is the third outer layer and has been prepared with polygonum leaves in the first layer and palm sheets in the second layer in advance. The basket is then sealed, commonly known as “muzzling the ox”.

Beating, Rolling and Tightening

The sealed tea scroll is still bulky and loose. Three different tightening techniques are used by the team repetitively until the ideal 20cm diameter is reached.

With the help of a long iron hammer, a team of up to 6 strong young men, doing a beating motion, press one end of the cylinder with the hammer to make the tea push towards the other end .

The second tightening technique is tramping and rolling the cylinder by foot. At the same time, the team is constantly tightening the bamboo threads. It is a spectacular scene to witness a large group of people working and chanting together.

The third tightening technique is when the team leader uses a large hammer to beat the tea brick and further squeeze the tea to tighten the cylinder. The team works together to create the correct dimensions.

49-days drying period

The shaped Thousand-Tael Tea should be placed upright under shelter for natural drying. 49 days (about two months) of “sun shining during daytime and dew absorbing at night” will provide the appropriate amount of water in the tea scroll by slow evaporation and redistribution. The tea scroll will eventually reach the optimal condition for long-term storage.

Preparation for consumption

To prepare the tea for consumption, an axe and a saw are needed. First the axe is used to cut the outer bamboo layer and then to tear the inner palm sheet layer. Next, a hammer and handsaw are used to slice the Thousand-Tael brick into tea cakes, quite similar to cutting an artisan bread to slices. Each slice is about the same size of a Pu’er cake. Finally a tea knife is used to slice pieces suitable for the volume of the teaware that has been selected to prepare the tea.

Retold by Si Chen

Renowned Chinese post-fermented tea

- Hunan province: Fu Brick Tea (Fuzhuan); Dark Brick (Heizhuan); Flower Brick (Huazhuan); Three Tip, including Heavenly Tip (Tianjian), Royal Tip, (Gongjian), Raw Tip (Shengjian); Thousand-tael or Flower Roll (Qianliang or Huazhuan). Locals summarize them as “3 bricks, 3 tips and 1 roll”.

- Hubei province: Green Brick Tea (Qingzhuan)

- Sichuan province: Golden Tip (Jinjian); Kang Brick Tea (Kangzhuan)

- Yunnan province: Pu’er (both raw and ripe)

Tea Market

Get More Value from Your Tea: BRU Maker One

+41794574278

Jacque's Organics

(647) 804-7263

I’m very eager to try this tea out, I take it that I should steep it much like pu’erh? Thank you for sharing about this tea, very well done!

@Teajourney – Thank you for the lot of information I appreciate any bit I find about dark tea.

–

@rstudd – only not to brew is done the wrong way!

Pu’er (either sheng or shu) is post-fermented and belongs in the dark tea group. Generally these teas are washed/warmed once for a few seconds and then brewed for drinking with boiling water. I mostly brew the gongfu way but you can also brew western (large pot, steep some minutes) or even leave the tea leaves in the teapot on a heating source. Experiment to find your preferred way. You can also add milk or/and sugar, herbs, spices, flowers, honey…

I have even seen offers of tea at shops selling tea mixed with coffee (kinda clash of titans). The only limit is your imagination.

– try different styles of brewing,

– it is about having a tasty enjoyable drink, it is not religion, it is not science

– keep in mind: only not to brew is done the wrong way

*****

Who am I? 48-year old former scientist now handicapped due to a tissue destroying chronic disease. I drink mainly Chinese tea the whole day long (I order directly from China) having more tea at home than an average supermarket (weight and classes and brands and…)

Currently drinking Hunan Anhua premium dark tea from COFCO China Tea – Dark Tea Garden HeiJing Zhuan from 2014 May 21st. It comes as 2 100g chocolate bricks in a black folding box with gold printing. Ah, and the brewing method is gongfu in a gaiwan 🙂

@AlexFromSwitzerland –

Great advice, thank you! I found I had to let this steep a little longer to really bring out the flavors and with the compact nature it helped to break it up some manually then steep with near boiling water. Great tea and thankful to this article!