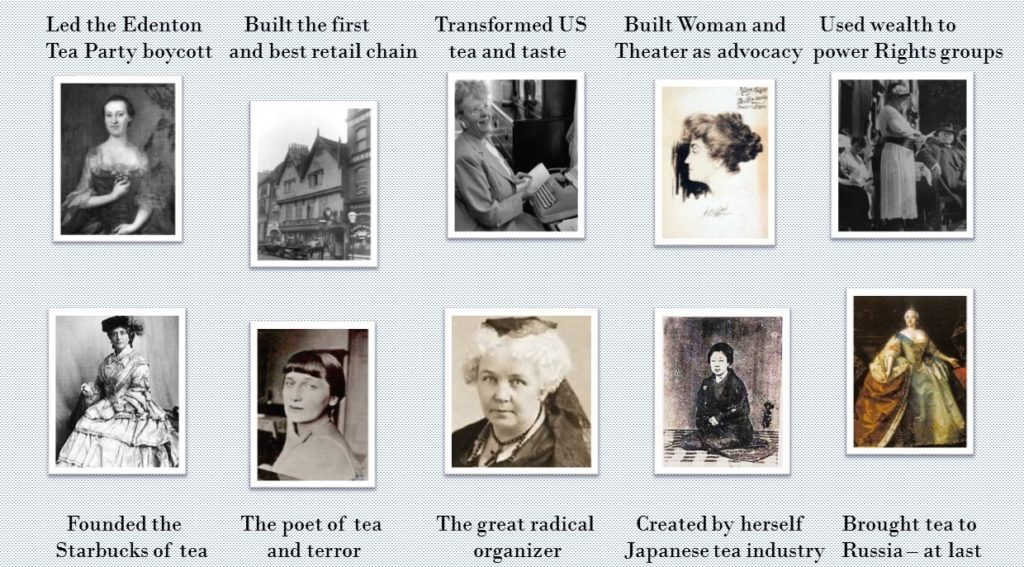

Ten innovative women who shaped the history of tea: social, political, trade, business, and cultural.

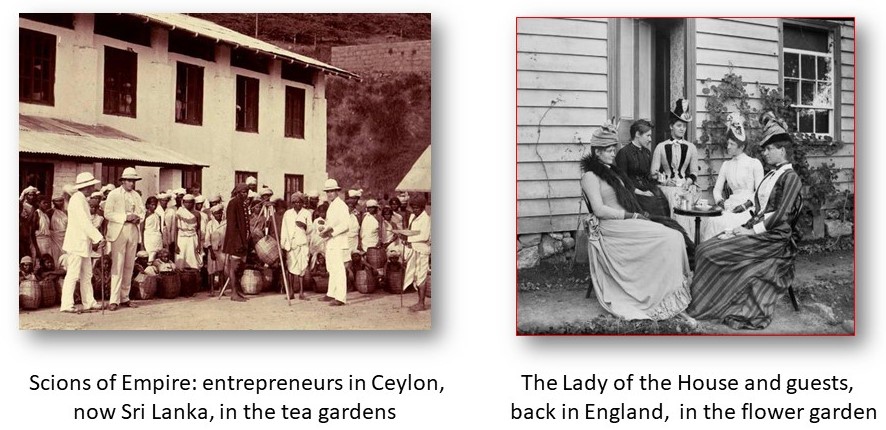

If you skim the standard history of tea, you’d conclude that men built the market, women drank the tea. Men drove the business, women shaped the social side. Here’s the stereotype from the Victorian era. Pith helmeted tea traders working in Ceylon and fashion hatted ladies relaxing in the garden. Together, these form the traditional view of tea cultures.

The exact variants of the stereotype range across time and settings. The men may be a group of soldiers, politicians, or writers. The women portrayed are aristocrats, maids or matrons. But the few historical women acknowledged in the history of tea are mainly passive walk-ons, not active innovators.

Catherine of Braganza is one of the most famous such notables, She was the Portuguese princess who is credited with introducing tea to Britain. Another is the Duchess of Bedford who formalized high tea. And, of course, Jane Austen is emblematic of the cozier aspects of tea partying. (It’s part of the ladies-at-tea trivialization. There is nothing cosy about the sharp Austen observation, irony and skewering.)

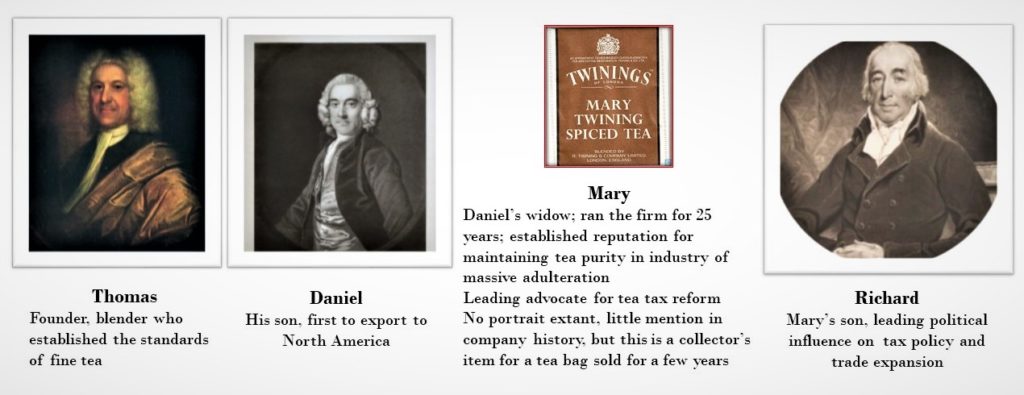

In this conception of tea history, women were obviously bystanders in innovation, or perhaps bysitters. Or just not there. Here are the first four stunningly successful leaders of the Twining company. Twining was the pace setter in the full commercialization of tea, starting in 1703.

The giants who built Twining tea are still in business at its 1703 location

Four outstanding figures, each remarkably accomplished, with long and successful careers. One is in essence written out of history. Twenty five years building up the small business to be a dominant market force and political influence… Setting the standards of quality in an industry where tea flavorings included sheep’s dung and poisonous cobalt colorings… Mary Who?

There’s a word for all this… But it’s unprintable so the British codswallop will do. “History” concerning 80% of the modern world of tea is masculine myth and feminine reality. The many female innovators of tea just don’t show up. Literally so. Here are just a few stories to begin redressing this.

Four tea breakouts

Four pivotal product innovations in the past 150 years created today’s market for the world’s most consumed beverage. These are the tea bag, iced tea, flavored tea and bubble tea. Together, they now account for at least 80% of the mass market. The four have shaped modern tea consumption.

Naturally, there has been an interest in who made the breakthroughs: the heroes. Here are the conventional credits and added “umm” comments. The credit belongs to heroines.

Tea bags

A British creation, of course. Nonsense. The UK held out against this alien American convenience or excrescence for around 50 years. (The labeling reflects if you really like tea or just drink it as wet and warm,) The agreed on narrative is that it was an accidental innovation. In 1908, Thomas Sullivan, a New York City trader, began to package samples in silk pouches. He discovered that customers were using them unopened to brew the tea. So, it took off as a product.

Umm…. Two Milwaukee women, had already patented the tea bag, in 1901. Roberta C. Lawson and Mary Molaren created a sophisticated and technically elegant design. It incorporated complex solutions to challenges of sealing, stapling and water flow. Sullivan’s bag, by contrast, is a neolithic design of a gauze pouch and a piece of string.

Iced tea

The standard story is that Richard Blechynden invented iced tea at the St. Louis World Fair in 1904. The scorching heat led him to dump ice in his teas rather than ineffectually try to sell them hot.

Umm… So much for all the recipes published since colonial times. And the commissioning of 2,000 pounds of “iced tea” by the U.S. Army in 1890.

The earliest published instructions for the recognized modern iced tea are those of Mabel Cabell Tyree. She published them in 1879, in a best-selling compilation of recipes from Virginia. Mrs D.A. Lincoln’s 1884 recipe is regarded as definitive. Mr. Blechynden left no trace beyond the anecdote.

Flavored teas

Earl Grey was the great innovator, of course, in the 1830s. No, no and no. Every single element of Earl Grey “history” is fiction, fantasy, falsehood and marketing flim-flam. In 2012, The Oxford English Dictionary set its thousands of volunteers on an in-depth search for published mentions. They found under ten references in the period 1830-1930. These were all an Earl Grey “mixture” for which the only ad on record is dated 1929. The tea is invisible in history till the 1960s.

In the world of reality, Ruth Bigelow began to sell her Constant Comment tea in 1945. It blended oranges and spices with black tea. This was a skilled adaptation of a colonial recipe. She focused on adding “zest” to the bland commodity teas on offer. That created the market for fruit flavored blends, including Earl Grey.

Bubble tea

This is the strange tapioca ball brew that has taken over Taiwan, Korea, Japan and Hong Kong. It is, alas, rapidly coming to a mall near you. Official story: invented by Mr. Liu Han Chieh. Reality: Mrs. Lin Hsiu Hui, his product development manager, at home and for fun.

Upper class myths

These innovators were ordinary folk, not high society icons. But it’s the nobs who get the central stage plaudits. In off-stage reality, their stories really are fluff. Catherine of Braganza brought tea with her in a diplomatic deal to marry Charles II, in 1662. Her tea stash was part of her massive train of 60-servant luggage. Tea had been an everyday drink among the Portuguese upper class for close to a century. Her “introduction” of it to the British court meant having it unpacked and served to her.

The Duchess of Bedford suggested that four p.m. would be a good time between lunch and dinner for Victoria’s chums to chat and nosh. It set a trend. That achieved, she passed into historical oblivion along with Richard Blechynden.

Women brought into the historical narrative were mainly refined hostesses and Duchesses with Texas Big Hair wigs. Their contribution to tea is that of sit-around stereotypes. This trivializes the impact of so many women. It trivializes tea, too. But it’s great marketing, adding an aristocratic association to well-packaged mediocre teas.

Ten women who transformed their times

Here are profiles of ten women who were agents of change whose impact rippled out, often widely. Some were key innovators in the world of tea. Others used tea as a core tool in political and social activism. They deserve to be highlighted, not hidden, in the history of the world’s most impactful drink.

Penelope Barker, American 1770s

The leader of the first organized women’s protest movement, known as The Edenton Tea Party, an effective and noted 1774 boycott of British goods following the Tea Act – the Boston Tea Party, without the violence.

of the first organized women’s protest movement, known as The Edenton Tea Party, an effective and noted 1774 boycott of British goods following the Tea Act – the Boston Tea Party, without the violence.

The initiative raised more than eyebrows. A major British newspaper savaged the women in a vicious and often-reproduced cartoon. Colonial protests were not new; one organized by women was.

Barker was clearly conscious of her role: “Maybe it has been only men who protested the king up to now. That only means we women have taken too long to have let our voices be heard. We are signing our names to a document, not hiding ourselves behind costumes like the way the men in Boston did in their tea party. The British will know who we are.” They did and they weren’t pleased.

Mary Tuke, English, 1725-72

One of the very first tea merchants and among the most outstanding across all eras. Built the first chain of stores in the tea and chocolate industry. Known as “the queen of confectionery.”

One of the very first tea merchants and among the most outstanding across all eras. Built the first chain of stores in the tea and chocolate industry. Known as “the queen of confectionery.”

It took her seven years to get a business license, with threats of jail and many fines. Women had almost no legal rights or identity, except as literal property of their husbands. She had to define sustained efforts to block her across the business establishment and city government..

Mary won out. She built a reputation for absolute quality in product and pricing. Her business was central to the growth of York, in the North of England, as the world’s “chocolate city.” Her shops were the base for the Rowntree empire and for Cadbury and Terry. These were dominant brands through to modern times for what she advertised as “exotic consumables.”

Oura Kei, Japanese 1850s-80s

This young woman by herself created the Japanese tea export market. Kei exploited Admiral Perry’s forced opening of the nation. By 30, in a country where women had minimal rights, she had built a new industry.

This young woman by herself created the Japanese tea export market. Kei exploited Admiral Perry’s forced opening of the nation. By 30, in a country where women had minimal rights, she had built a new industry.

“O Kei” brokered tea from small growers. It took three years of struggle to amass four tons to meet her first contract. She persuaded farmers to focus on a new type of tea, sencha. This was aimed at US drinkers’ preferences.

Oura Kei was the force that built Japanese teas to over half of US imports in under thirty years. She was a brilliant manager and highly respected for character and competence. Sencha is now Japan’s main tea.

Ruth Bigelow, American 1945-1960s

Transformed the US tea market through her creation of Constant Comment orange-infused spiced tea. Led the shift to flavored teas that predates Earl Grey and herbal teas.

Transformed the US tea market through her creation of Constant Comment orange-infused spiced tea. Led the shift to flavored teas that predates Earl Grey and herbal teas.

She built Bigelow from a kitchen operation to one of the top two blenders in the US market. It was the first US major tea brand. She led innovations in packaging that help set new standards of quality control.

Most of Bigelow teas are now commodity bags but Constant Comment was a superior and original tea. Many experts claim that it changed taste in the USA. It led, rather than followed, Earl Grey as a product. (The name came from early tasters coming up with words to capture its unusual flavor.)

Elizabeth Stanton, American 1840s-1902

One of the most effective leaders in the US in the movements for Women’s Rights, for over fifty years. Titanic and tireless. Tea is a constant thread in Stanton’s narrative. This was symbolized by her iconic three-foot traveling tea table. She first used it publicly at her gathering together women who mobilized from all social classes for a tea event. That was the convention that resulted in the 1848 Seneca Falls Declaration of Sentiments.

One of the most effective leaders in the US in the movements for Women’s Rights, for over fifty years. Titanic and tireless. Tea is a constant thread in Stanton’s narrative. This was symbolized by her iconic three-foot traveling tea table. She first used it publicly at her gathering together women who mobilized from all social classes for a tea event. That was the convention that resulted in the 1848 Seneca Falls Declaration of Sentiments.

The Declaration was the pivotal opening salvo in the “grand movement” for female suffrage. It was signed on her tea table. Tea was a binding force in all her mobilization for action. This emblematic small piece of wooden furniture was placed at the head of the casket of Susan B. Anthony at her 1906 funeral.

Mary Shaw, American 1900-20s

One of the finest classical stage actresses of her era. She worked incessantly to use her own talents and those of fellow actresses. They built a powerful advocacy force for women’s rights.

One of the finest classical stage actresses of her era. She worked incessantly to use her own talents and those of fellow actresses. They built a powerful advocacy force for women’s rights.

She helped set up tea “clubs” designed to be a “halfway house for rest and rendezvous.” They offered canteens, ladies only rooms and meeting facilities. Women’s Rights leaders exploited the familiarity of tea to obscure their use of it for anti-authority subversion. The New York Times criticized this as tea bait.

No one subverted as brilliantly as Mary Shaw.

Elizabeth Petrovna, Russian 1730s

The Russian Empress who brought tea to Russia after centuries of failed China trade negotiations. She also brought to Russia a minor German princess, Sophie Frederike Auguste-Anhalt-Zornburg to marry her (abominable) son.

The Russian Empress who brought tea to Russia after centuries of failed China trade negotiations. She also brought to Russia a minor German princess, Sophie Frederike Auguste-Anhalt-Zornburg to marry her (abominable) son.

We know that daughter-in-law as Catherine the Great. She deserves the title. Catherine was one of the most extraordinary, dramatic, intelligent, compelling and powerful royal rulers in history. Elizabeth was one of the toughest.

Their policies on tea established it as central to the emergence of a national identity. This is represented by the samovar, a Persian import that became symbolic of Russia.

Catherine Cranston, Scot 1880-1930

Built a renowned chain of tea rooms in Glasgow. The growing popularity of tea opened opportunities for women to offer tea and light refreshments from their homes. Hotels began to set aside space for afternoon tea.

Built a renowned chain of tea rooms in Glasgow. The growing popularity of tea opened opportunities for women to offer tea and light refreshments from their homes. Hotels began to set aside space for afternoon tea.

Cranston’s Willow Room was a step shift ahead. “Kate Cranston-ish” became a commonplace for stylish and elegant. She befriended leading architects and art nouveau designers to establish unparalleled ambience and panache.

Cranston was the first creative inventor in a business of merchants. She made her tea rooms welcoming to the working class and inexpensive.

Alva Belmont, American 1880-1930s

The ultra-wealthy powerhouse activist for Women’s Rights. She despised rich women who gave money to causes but did nothing else. Descriptions of her are usually variants on formidable, intimidating, indefatigable and militant.

The ultra-wealthy powerhouse activist for Women’s Rights. She despised rich women who gave money to causes but did nothing else. Descriptions of her are usually variants on formidable, intimidating, indefatigable and militant.

She brought a new radicalism to the somewhat genteel US movement. This was akin to the suffragettes of Britain, who confronted police opposition publicly and were frequently jailed. As Belmont once commented: “you talk, we act.”

Belmont knew how to organize. She founded Suffrage organizations and used her many social contacts to raise money and mobilize women. Her wealth enabled her to build refuges and leverage tea rooms as organization centers. One of her innovations was sponsored tea events used very much as the equivalent of today’s social media.

Anna Akhmatova, Russian 1920s-60s

The author of one of the greatest poems of the past century: Requiem. She chose to stay in Leningrad after its near destruction in World War II. Stalin ordered her unremitting personal persecution. She could communicate her poems only orally, in secret.

The author of one of the greatest poems of the past century: Requiem. She chose to stay in Leningrad after its near destruction in World War II. Stalin ordered her unremitting personal persecution. She could communicate her poems only orally, in secret.

Akhmatova survived the imprisonment of her son, execution of husband and ex-husband, and unrelenting poverty.

Tea is a dominant flourish in her poems and part of her very identity. It was also core to her survival and often all she lived on. A friend said of her that when you are poor, you still had something to lose. “Anna had nothing.” As she herself wrote “It was a time when only the dead smiled, happy in their peace.”

These were women of immense character, achievement and impact. It’s time to write them back into the history of tea.

Tea Market

Get More Value from Your Tea: BRU Maker One

+41794574278

Jacque's Organics

(647) 804-7263