A view from the tea garden. Photo by Greg Goodmacher.

A view from the tea garden. Photo by Greg Goodmacher.

Yamazoe Village, Japan

My guide drove up impossibly narrow, curving roads toward the highlands of Yamazoe Village, Nara, Japan, where wispy mist slipped through the tips of lush green forested mountains. The Nabari River glistened below us. When we parked in a grass field on the shoulder of one verdant plateau, we heard a male pheasant squawking somewhere behind weather-stained wooden farmhouses. So began my introduction to a hands-on tea workshop in one of Japan’s loveliest tea-growing neighborhoods.

Run by farmers and other locals, the workshop taught me to select raw leaves and transform them into sencha tea using centuries-old techniques. The tea production method involves roasting the tea in a pan, called kama in Japanese. Local tea experts sometimes describe the tea as kamairi-made tea (pan-roasted green tea). The resulting tea beverage can be called kamairi-sencha.

Fresh tea leaves from local growers are used to make sencha. Photo by Greg Goodmacher.Following Japanese custom, I removed my shoes, donned slippers, and entered the classroom in an old kindergarten building, now used for community events. A friendly group of around twenty people: enthusiastic tea connoisseurs, a professor of agriculture and marketing, his students, and local tea farmers greeted me.

The village of Yamazoe, population 3,700, is in Nara Prefecture, about 80 kilometers east of Osaka. Nearby gardens include Kasuga Tea Garden and Mitocha Tea Farm.

Kenichi Ikawa Sensei, our teacher, drew pictures of tea plants and world maps with chalk on a blackboard while giving us a tea quiz to break the ice. Excited and knowledgeable, participants raised their arms high or shouted the answers.

Then, he displayed tea stems and showed which leaves to pluck for our workshop. Our instruction was to pick two or three soft green leaves at the end of the tea stems.

We then moved into a chairless room where bunches of freshly picked tea branches piled on circular bamboo trays waited. We broke into groups of three to five people and sat on the floor around each tray. We were to pick and place the tender young leaves in a woven reed basket. Discarded leaves and stems would become compost.

Roasting the leaves on large blackened iron pots was the next step. First, one of the tea workshop assistants tipped the leaves containers into heated woks. He instructed us to gently press the leaves against the pot and then lift and spread them evenly for consistent roasting. The leaves shrank. Aromatic steam wafted off the three hot wok-like pots. Impatient for our turns, we stood in lines for the opportunity to mix the tea and lift it toward our noses, immersing ourselves in the herbal fragrance and hurrying to the end of the line to do it again.

The hot tea leaves needed cooling for the following step. We accomplished this by waving hand-held fans over the tea.

The roasted leaves were moist. Consequently, removing the moisture was the next stage. We grabbed a loose handful of tea and placed it on a square cloth approximately the size of a table napkin. While squatting on the hard wooden floor, we pressed the tea into the center of the material and squeezed the fabric around the leaves, forming a tightly compressed ball. Holding the fabric tightly with one hand, we kneaded the tea ball back and forth for several minutes with one palm. The cloth absorbed moisture from the roasted tea leaves. The college students in their early twenties, unaccustomed to such physical effort while sitting on a floor, said this work was tiring and uncomfortable. Meanwhile, the older Japanese people were unfazed.

After the cloth had become wet, we unrolled the tea balls and placed these again into the hot pots, and repeated the roasting, cooling, and rolling steps twice. Each time, the room became more fragrant. Finally, during the third roasting, I placed my face close to a clump of warm tea. My face felt as if I were in a tea sauna. Savoring the moment, I closed my eyes and deeply inhaled the roasted green tea aroma.

Everyone chatted amiably about tea and their reasons for joining the workshop during wait times between various steps. During break time, we ate a box lunch prepared with all the local ingredients; many, such as Mr. and Mrs. Yoshizawa, had previously attended. They learned about the tea workshop when their daughter’s class participated in an elementary-school event. The beauty of the countryside, the deliciousness of the tea, and the enjoyment derived from the experience are why this was their seventh workshop despite a nearly one-hour drive.

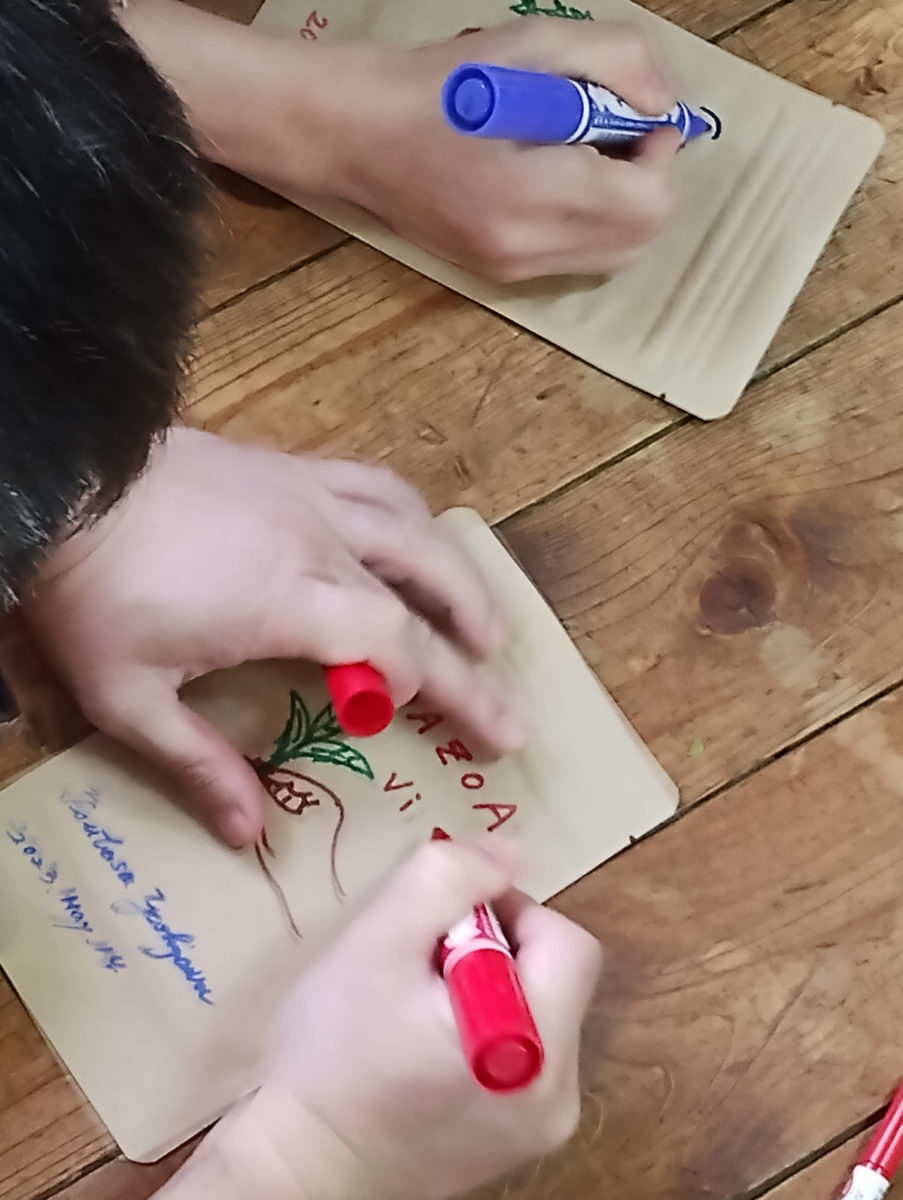

After finishing the tea processing, we received marking pens and packages for taking the tea home. Then, like children, we sat on the floor and decorated our bags with drawings of mountains, the sun, tea leaves, and other images.

Finally, we returned to the first classroom to enjoy the fruit of our labor. With slow, sure movements, Ikawa Sensei poured water at approximately 70° degrees Celsius (158° Fahrenheit) into a clear glass teapot. He waited three minutes before serving. We all called out kanpai (cheers) before savoring the thick, fulfilling liquid that left a lingering aftertaste. Then, he poured approximately 85° degrees Celsius (185° Fahrenheit) water on the same leaves, which he steeped for one minute. Finally, Kenichi Sensei prepared the last yummy cup with water at 100° Celsius (212° Fahrenheit).

I do not know the precise vocabulary to explain the nuances of taste I absorbed, but it was the freshest and one of the most delicious teas I have ever been privileged to drink.

The fee for this experience of about five hours, a healthy lunch, and a generous package of organic tea to take home was a mere 1,500 yen (approximately US $11). This was not a money-making endeavor for the teacher and supporting staff. Kenichi Sensei explained that he teaches the workshop for the joy of camaraderie, the warm atmosphere, and a love for tea.

Visit Yamazoe, Nara Prefecture, Japan

Click to see a video of this tea-making experience. Follow this link to join future experiences. Examine the Kasuga Garden on Facebook to learn about other local agricultural events and workshops. You can also call 0743-85-0048.

For more about tea and other wonders of East Nara, read the website of the East Nara Nabari Tourism organization.

For information about my tea teacher and his delicious products, click here (Japanese only).

Tea Market

Get More Value from Your Tea: BRU Maker One

+41794574278

Jacque's Organics

(647) 804-7263

What a nice story,

I could almost smell the scent of the cloth-crushed leaves, first time I read about such a tea making process, with the leaf becoming infusable in so little time, but how come the leaves were on the stem?? I guess the picking was carried out by a ride on harvester?

thank you for sharing!!

Hello Barbara,

Thank you for your comment and question. The picking was done by hand by locals who brought the stems to the classroom for attendees to choose the best leaves. The original plan was for attendees to pluck the leaves off the bushes, but the plants are on a steep slope, and that morning heavy rain fell on the field. The locals worried about attendees slipping, so they picked the stems and brought them into the classroom for us.