Managing a Tea Garden at 12,000 Kilometers Distance

On Monday morning, at 5 am Nishchal Banskota wakes up to begin work. He’s a tea farmer from Nepal, now running the famous Kanchanjangha Tea Estate. He’s meeting a group of people, including his father, Deepak Prakash Baskota, the 74-year-old chairman of the company, the factory supervisor, the accountant, the garden supervisor, and his sisters who are also a part of the estate. In an hour’s time, problems are discussed, tasks are assigned, goals are assessed and the meeting is done. Post-meeting, Nishchal enjoys the greenery in his immediate vicinity. He brews a cup of 2019 Kanchanjangha black tea (that he has christened Moonlight Black) ruing that his stock is dwindling and it may be a while before he can get more of it. Outside, lights blink from the skyline of East Manhattan past the East River. It’s dark but waking up as only New York City can.

The pandemic has created new ways of working for many, and for Nishchal, it’s made him a remote farmer. From his Long Island home, Nishchal has found that connecting with his family and colleagues in faraway Nepal can actually work.

Says Nishchal, “When the pandemic began, I was very nervous. We didn’t go out for 55 days. New York City was the epicenter. All business activity was shut down. The exporting unit was shut. Our teas had been produced but were not moving. We had no exports, no idea what to do.” But with exports down and business slow, he had a lot of time on his hands. With great foresight, he decided to focus on how they would be back on their feet when the lockdowns ended and business could resume. He spoke to his father and three of his sisters who are involved in the business (Nishchal is the youngest of eight siblings) and they decided to meet online every Wednesday.

The first couple of meetings went well … Nishchal wanted everyone to share why they were each in the tea business and what their aspirations were. “It surprised me that we were in the same family but didn’t know what each of us wanted. It was the first time we were articulating what tea was for us.”

There was a lot of talking and planning and ideating, and then came the task of putting the new plans into action. “The beauty and harsh reality of being in a family business,” admits Nishchal, “is that you can’t say who is monitoring the other.” Without one single person to lead, everyone was doing everything. Soon, Nishchal, with his degree in business, was tasked with leading the team.

A bit of the back story

In 2015, soon after he finished college in New Hampshire, Nepal suffered one of its worst earthquakes in recent history. Nishchal returned to volunteer for 3-months. Before his time was up, he had decided that he wanted to work in the family’s tea business.

“Think about it,” his father advised. “It’s easy to get into the tea business but you can’t get out.” Although he didn’t understand exactly what his father meant, Nishchal spent nine months in Nepal, most of it on the tea farm. One of his sisters was working on streamlining domestic distributorship of the tea, which was struggling against indiscriminate blending. The Baskota Group, under her, became the exclusive marketing arm of Kanchanjangha Tea in Nepal. Nishchal joined her.

In 2016, he returned to New York and set up Nepal Tea LLC, to create an identity for teas from the region and to begin exports. Everything was going well except his father wanted him to be on the farm in Nepal. “I couldn’t find time to do that,” he says. Every time father and son spoke, a question was, “Can you come and run the farm here? I will pay you well.”

His father was able to visit the farm only once in two months, and Nishchal could see that this non-availability was not helping the team on the ground. Production was decreasing every year, and the future of the estate was “in god’s hands,”

And then the pandemic arrived.

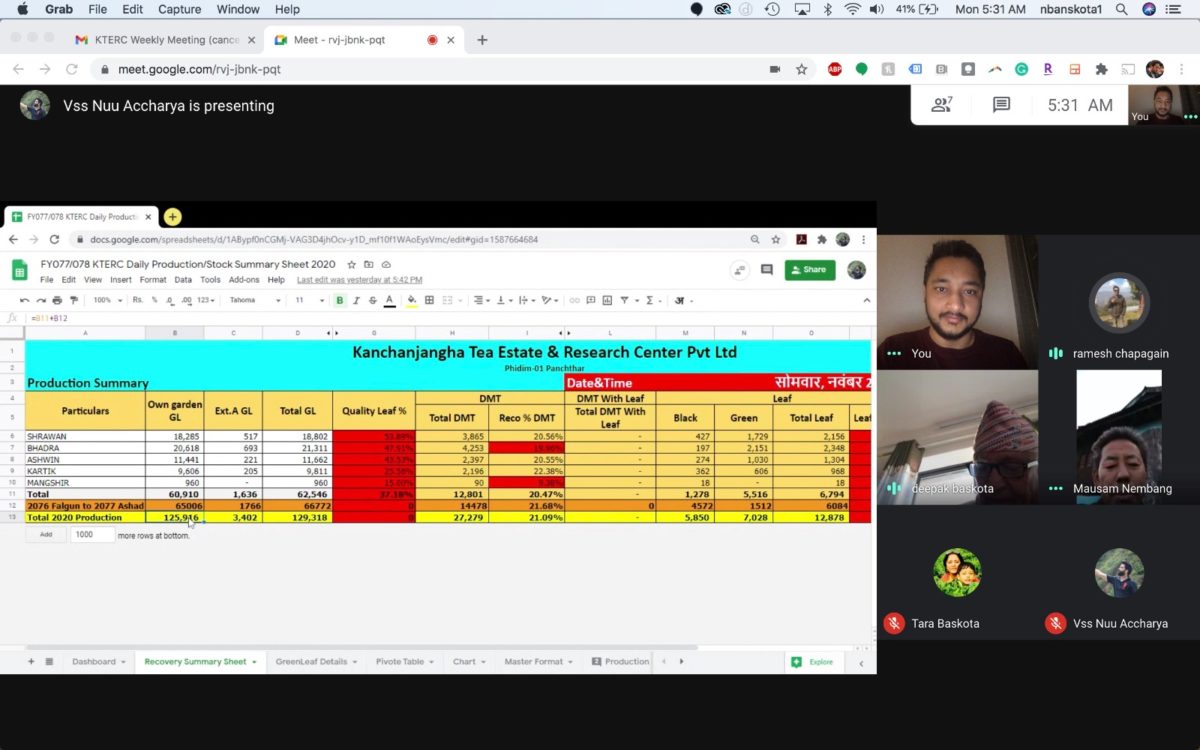

Now, speaking weekly with his family, the problem to solve was on decreasing production. Reducing manpower was blamed as the reason why. Nishchal began working with his accountant (over Zoom) between New York and Nepal every day. Together, they analyzed data for 11 years and arrived at the conclusion that production had decreased by almost 50% in 11 years but manpower had come down by only 23%. They also found that there were irregularities among some staff, that no one was monitoring the recovery rate or how much green leaf was coming in and how much tea was being produced.

Breaking barriers to increase efficiency

“I am inspired by Jack Stack, the author of The Great Game of Business,” says Nishchal. It’s almost compulsory reading for his team these days, for the method it endorses — the Open Book Method. He calls it a game-changer. Nepal, like much of South Asia as a culture that is built on hierarchies. There are barriers inbuilt between management and farmers. It’s an old way of being and working and Nishchal was trying to break it or at least bridge the gap.

To the weekly meetings, which were still amongst the family, were invited the accountant, factory manager, garden manager, tea maker, and garden supervisor. Those living on the farm were given cell phones with mobile data to be able to be on the call. Says Nishchal, “Initially the reaction was, let’s humor the Chairman’s son. It would take about 45 minutes before everyone was on Zoom. It was frustrating.” But it took not more than a couple of meetings before the team started taking him seriously. And Nishchal began giving everyone targets and numbers, from leaf quality and percentage to recovery rate and orders.

The meetings have now fallen into a pattern. Every Monday, they start with the garden and cover the entire life cycle of production. Problems are aired, tasks assigned, solutions offered, goals are set. More importantly for Nishchal, everyone is talking to each other regularly. There is new energy, he says.

He talks about Jack Stack and motivation. Incentives were introduced, even if his father needed convincing about it. The goal for the year was to aim for a 25% increase in quality production. They expected to reach it in November 2020 but met the mark by October, making 2020 the highest production year in six years. “Everyone is getting a big bonus,” says Nishchal.

Making a wishlist

The team also began planning an emergency fund back in March. There were not too many COVID-19 cases in Nepal at the time but he sensed it would get worse. The Nepal Tea Foundation was set up as a non-profit and the prices of their tea were increased by $1. These funds trickled into the Foundation and by the time the country experienced the worst of the cases, it offered a cushion for wages and medical help.

But it’s not all numbers for Nishchal. He goes on to say, “I want to see my farmers smiling.” So he sent off his managers to find out what his team on the ground wanted, what were their aspirations, what were their desires. Two weeks later, the manager returned with two requests: The staff wanted more social gatherings, and two, they wished to travel to a few famous places within Nepal since most of them had never seen anything beyond their village.

It seems to have hit a chord with Nishchal. A monthly picnic was easy to put in place but Nishchal is already dreaming of renting a big bus to take his team on a tour around Nepal. He asked the same of the staff in his exporting unit. Many here are illiterate older women and they now expressed a desire to learn to read and write. Plans are on to begin literacy lessons.

On Father’s Day this year, the family got together, on Zoom, across the US and Nepal. Nishchal’s gift is that he will do what it takes so that his father can retire in the next two years. Confident now that distance need not impact the business, the family is busier than ever.

The remote farmer

“The pandemic was the worst thing to happen but there was a silver lining. It radically changed how we work. But for a pandemic, I would have never thought of a Zoom call,” says Nishchal, over our call between Long Island, USA, and Bangalore, India. It’s early morning for me, and the end of the day for him. “I have more confidence that I can manage a farm remotely,” he says. “I can’t leave this now. My father was right. It is very difficult to get out. This is my life now. I don’t think I will be doing anything else. I am a farmer, of another kind.”

Tea Market

Get More Value from Your Tea: BRU Maker One

+41794574278

Jacque's Organics

(647) 804-7263