- A growing body of studies of leaf chemical composition is beginning to support the experienced tea maker’s choices.

- A striking difference is found in chemical composition as you go from the shoot to lower leaves.

We often hear that the best loose-leaf teas come from buds or shoots, the still-furled newborn leaves at the tip of a twig, while tea made from older leaves lower down on the twig give teas of lower quality. To determine whether this is true, we should consider the chemistry of each age of leaf, and importantly, the intentions of the tea maker.

See: Why Tea Leaves are Plucked in the Morning

There are striking differences in chemical composition as you go from the shoot to lower leaves. The shoot itself is covered with a down of tiny hairs called trichomes. Trichomes serve to protect the tender shoot from UV light and from insect attack. These hairs appear to contribute a greater umami taste and less bitterness and astringency than does the leaf itself, due to their higher content of amino acids and lower content of polyphenols (1). In other words, it’s the hairs’ direct contribution that make shoots so desirable for making green and white teas and the teas derived from green tea, such as pu’er and yellow tea.

![Jiang X, et al. (2013). "Tissue-Specific, Development-Dependent Phenolic Compounds Accumulation Profile and Gene Expression Pattern in Tea Plant [Camellia sinensis]". PLOS ONE. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0062315. Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 3.0.](https://teajourney.pub/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Tissue-Specific-Development-Dependent-Phenolic-Compounds-Accumulation-Profile-and-Gene-Expression-pone.0062315.g004.png)

Lignin forms in the walls of leaf cells, particularly the walls of veins; the older the leaf, the larger the veins, and the greater the amount of lignin available. When heated, lignin contributes roasted flavors to a tea. Excessive amounts of compounds derived from lignin, such as guaiacol with its smoky aroma and methoxyphenols, which are sweet and slightly medicinal, would detract from the flavors of a green tea, but may contribute to those of black teas.

The common assumption, then, is that the best teas are plucked as a shoot and one or two leaf standard, but oolongs are often plucked at a different standard, namely 2 to 3 slightly opened leaves (e.g. Dan Cong), one young and two mature leaves (e.g. Tie Guan Yin), and one young and 2 mature leaves (e.g. Que She, Qi Dan). Similarly, quality black teas are often made from opened leaves.

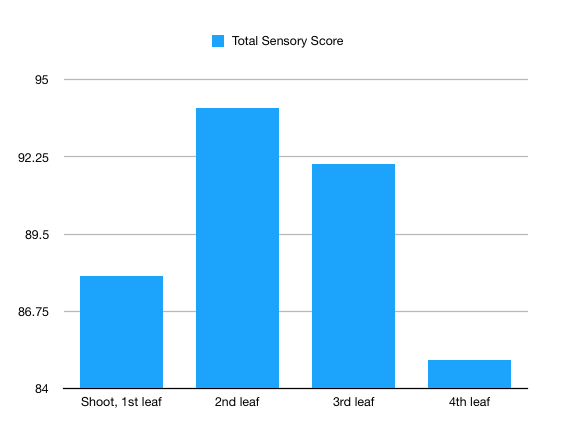

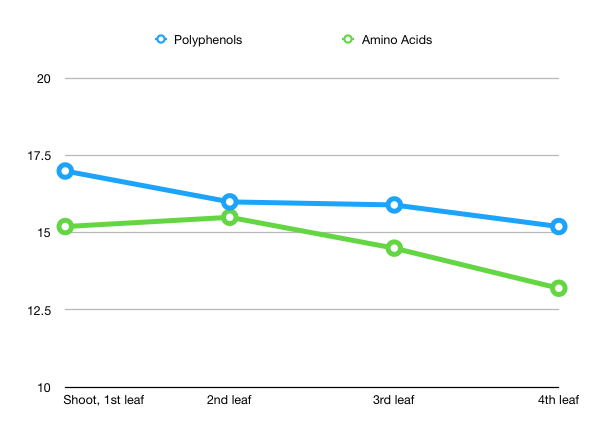

Y.-Q. Xu and colleagues examined the properties and sensory qualities of Tie Guan Yin tea produced from only the shoot and first leaf, or the second leaf, third leaf, or fourth leaf. The graphs at right and below are derived from the data they presented (4):

The first graph shows the total quality scores—the second leaf provided a significantly higher quality score. The second graph (below) shows the reason why, namely that the ratio of polyphenols to amino acids was lowest for the second leaf. Both amino acid and polyphenol content decrease as you go from shoot to fourth leaf, but the polyphenol content drops more quickly from the shoot to the second leaf, while amino acid content remains steady. For oolongs, the higher the ratio of sweetness (amino acids) to bitterness (polyphenols), the higher the quality (5).

Total sensory score = sum of color (0-20), taste (0-40), and aroma (0-40).

Polyphenol and amino acid content of Tie Guan Yin made from different leaves, in mg/g; polyphenol values indicated are divided by 10.

That said, recent data suggest that another contributor to the sweetness of teas made from the lower leaves may be in the leaf’s cuticle. Cuticles are the waxy layers on the top and bottom of a leaf that render it waterproof and help to protect the underlying cells from UV light damage. As you go down the twig, leaves have thicker and thicker cuticles (6). Among the chemicals contained in this layer are triterpenoids, which are known to contribute to the sweetness of oaked wines (7). With respect to the tea leaf, the lower the leaf the greater the amount of triterpenoids per gram (6). Whether triterpenoids contribute to the sweetness of teas made from lower leaves is not known.

Carotenes provide major substrates for the floral aromas of oolongs and black teas. Carotene content increases as you go down the twig (9). Similarly, lower leaves have more chlorophyll (9), probably because lower leaves receive less sunlight—at low levels of sunlight, carotenes, and carotenoids assist chlorophyll in capturing energy.

Methyl salicylate is a distinct and delicious aroma component of black tea, providing a sweet wintergreen quality. While the leaf’s content of terpenoids with their aromas decreases with leaf maturity, methyl salicylate increases, another reason to choose a leaf further down the twig for making black tea (10).

In sum, the tea maker develops a plucking standard through years of experience; a growing body of studies of leaf chemical composition is beginning to support the tea maker’s choices.

Footnotes:

- Zhu, Mingzhi. et al. Metabolomic profiling delineate taste qualities of tea leaf pubescence. Food Research International, 94:36-44, 2017.

- Liu, Zhi-Wei et al. L-Theanine content and related gene expression: novel insights into theanine biosynthesis and hydrolysis among different tea plant (Camellia sinensis L.) tissues and cultivars. Frontiers in Plant Science, 8:498, 2017.

- Li, X. et al. Developmental changes in carbon and nitrogen metabolism affect tea quality in different leaf position. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry, 106:327-35, 2016.

- Zhang, Z, et al. Evaluation of sensory and composition properties in young tea shoots and their estimation by near infrared spectroscopy and partial least squares techniques. Spectroscopy Europe, 23(4):17-21, 2011.

- Xu, Yong-Quan et al. Quality development and main chemical components of Tieguanyin oolong teas processed from different parts of fresh shoots. Food Chemistry 249:176–183, 2018.

- Hung, Yueh-Tzu et al. Sequential determination of tannin and total amino acid contents in tea for taste assessment by a fluorescent flow-injection analytical system. Food Chemistry, 118:876–881, 2010.

- 7. Zhu, X. et al. Tender leaf and fully-expanded leaf exhibited distinct cuticle structure and wax lipid composition in Camellia sinensis cv Fuyun 6. Science Reports 8, 14944, 2018. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-33344-8

- Gammacurta, Marine et al. Triterpenoids from Quercus petraea: identification in wines and spirits and sensory assessment. Journal of Natural Products, 82:265-275, 2018.

- Wang, X. Et al. Genotypic variation of beta-carotene and lutein contents in tea germplasms, Camellia sinensis (L.) O. Kuntze. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis, 23:9-14, 2010.

- Samanta, T. et al. Changes in targeted metabolites, enzyme activities and transcripts at different developmental stages of tea leaves: a study for understanding the biochemical basis of tea shoot plucking. Acta Physiol Plant, 39:11-17, 2017.

Reading this article was an educational experience.