Barbote, Nepal

Orthodox tea production by Nepalese smallholders started just 44 years ago when 41 farmers located on the periphery of Ilam joined the Nepal Tea Development Corporation (NTDC), recalls third-generation grower Narendra Kumar Gurung. His grandfather, who founded one of the first gardens in Barbote, was among those “courageous farmers” who now operate 14,014 small and medium-sized tea gardens across Nepal.

Nepalese farming is traditional, and subsistence in nature. Commercial crops like tea were grown in the country’s eastern reaches on large government-owned tracts of land. This is why the gradual shift towards identity as a specialty tea origin took four decades, explains Gurung.

Tea growing, encouraged by government agricultural training and incentives using predominantly Chinese varieties, has since expanded to higher elevations in the central portions of the country, with medium operations covering 7,060 hectares of land and smallholders cultivating 9,845 hectares (58%). Only 1% of Nepal’s tea acreage is under large-scale production.

Gurung explains that “Nepal’s tea cultivation practices are completely different than many other countries. Here tea farmers still have a patch of maize, paddy, vegetable gardens along with the fodder and pastureland as well, thus tea is a part of agro-silviculture practices in Nepal.”

Silviculture is the art and science of controlling forests and woodlands’ establishment, growth, composition, health, and quality. In Nepal, tea co-exists in an environment where wildlife, timber, water resources, and food crops are cultivated in harmony.

Barbote is a village named for the ashvattha or bodhi tree (ficus religiosa). These 100-foot tall sacred figs are planted along the rural lanes. The farm is part of Highlanders Farmers Private Ltd., which operates a small processing facility with a capacity of 60 kilos a day and a homestay program. The land supports tea and coffee, kiwi, Shiitake, Macadamia, and other cash crops. The village is five kilometers from the Ilam Bazaar at an elevation of 4,750 feet (1,450 meters)

“The busy season for traditional crops (maize, millet, paddy) does not collide with the tea plucking and pruning season,” writes Gurung. “This is one reason why tea became part of the farming system in Nepalese agriculture. They are complimentary and supplement each other. Animal manure, for example, is ideal for the tea bushes and forages removed from the tea garden are taken for the cattle,” he said.

Evolution of specialty tea segment

Barbote’s tea bushes are some of the earliest planted in Ilam, where a gift of seeds was first sown in 1873, a period when cultivation in Darjeeling, India, first advanced. Gurung said that his grandfather planted Chinese clones in the 1920s. Once cultivation started expanding on a large scale in the 1980s, his father planted Tadga, Gumtree, some AV2, Fupthsring, and Benettbone cultivars.

Gajaraj Singh Thapa, governor-general of Ilam, established the first modern garden in Ilam. The 100-acre Soktim Tea Estate followed two years later when planting began in the Jhapa district. While a young captain in the service of the King, Thapa had lived in Darjeeling under the tutelage of Brian Hodgson at Brianstone’s estate. The tea he planted was a gift from the Chinese to his father-in-law, Nepal’s prime minister at the time.

The first private investment in tea plantations was the Bhudhakaran Tea Estate planted in 1959 in the Terai. These tall grasslands of scrub savannah, sal forests and swamps are located beyond the outer foothills of the Himalayas and extend across the Indian border. Tea from the plains is from Assamica plantings and is of average quality. Domestic per capita consumption is about 200 grams per year, much of which is chai.

In 1982 King Birendra Bir Bikram Shah Dev declared five districts for commercial plantings in a “tea zone” encompassing Jhapa, Ilam, Panchthar, Dhankuta, and Terhathum.

The NTDC was formed in 1966 when most leaves were sold to Indian tea producers in Darjeeling. The first Nepal processing factory was erected in 1978 with a second factory in Soktim. Nepal’s first private orthodox factory was erected in 1993 at Maloom Tea Estate.

In 1997 government-owned plantations and factories were sold and operated under the direction of the NTDC.

Once tea factories began operating in Nepal, Gurung notes that the introduction of tea as a second crop led to substantial farm income for independent growers and a daily wage for farm laborers on the larger farms.

“Almost all the tea garden owners, small or medium, have their own tea puckers and workers skilled in garden management, thus, unlike in big tea gardens in other countries, there are no issues with organized labor,” he said.

“Interestingly once specialty tea production began with Chinese processing equipment in the last 10-12 years, some of these tea farmers turned into the tea manufactures as well,” he writes. There are now 125 small and medium tea manufacturing factories producing specialty tea. These Tea Small and Medium Enterprise (Tea SME) differ in the scale of operation and ownership. Investment groups and cooperatives own some, but all still involve the garden owner.

The NTCDB writes that Nepal produces about 25,000 metric tons of tea annually. Jhapa district gardens account for more than 75% of the tea grown in Nepal (17,500 metric tons), followed by Ilam, which produces about one-sixth (6,500 metric tons). In 2019/20, Nepal produced 15 million kgs of CTC and 9 million kgs of orthodox tea, exports totaling $23 million.

Around 80% of Nepal’s orthodox production is exported to India at low prices due to the lack of organic production processes and related certification. Export volume declined, but value increased 41.4% in 2020. Nepal worked without interruption as COVID-related setbacks caused India’s tea production to decline. The World’s Top Exports, citing figures provided by the World Trade Centre, estimated tea export value at $33.4 million, which ranks 24th globally. NTCDB reported exports at 11,185 tons. By comparison, India ranked 4th with $700 million in exports.

Tea lands expand

As growers began planting tea at higher elevations, in Kaski, Dolakha, Kavre, Sindhupalchok, Bhojpur, Solukhumbu, and Nuwakot, farmers began developing the knowledge of tea cultivation, plucking, bush management, and tea manufacturing, now followed by marketing, which is still in its embryonic stages, explains Gurung.

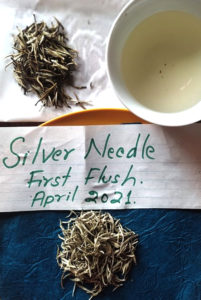

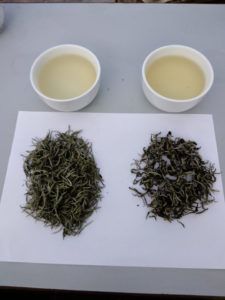

“Specialty teas, such as green tea, white tea, golden tea, oolong, silver needle, golden needle and so on utilizing the whole leaves are now produced in tea hamlets across the Ilam district. These types of teas are distinctly different than the traditional Special Finest Tippy Golden Flowery Orange Pekoe (SFTGOP) style. While it has been only a decade, specialty has achieved a special identity for Nepal in the world tea atlas,” he said. Sixty percent of the orthodox tea produced in Nepal is exported to Europe and Japan. The US, China, and Canada are among the more promising emerging markets.

One of the significant advantages of cultivation in the highlands is that one tea garden’s terroir is entirely different from another, he explains. “This enables us to offer quite distinct quality specialty tea suited to the diverse needs of consumers,” he said.

Nepal’s first flush begins in March, and the second flush starts in mid-May. Monsoon tea is harvested from July through September. The autumn flush begins in October.

Eastern Nepal, for example, has distinct micro-climatic variations from one ecological belt to another, with the altitudinal and longitudinal difference over two to three kilometers sufficient to have a direct and substantial impact on the tea quality, he explains.

The local factories produced between 113,00 and 133,00 kilos of raw leaf valued at NPRs7-8 million (about $60,000-$67,000 US dollars). “Tea pluckers coming from each tea farmer’s house and sometimes daily wages earners, organize themselves to pluck individual gardens as a group, leading to good coherence,” said Gurung.

To make the most of the differences in terroir, workers sort the leaves after a long day of plucking to segregate the buds for which they are paid separately. “A female tea plucker harvest about 15-20 kilograms of fine leaves daily and when paid to segregate the buds, she can earn an average $10-$15 per day, which is significant income to support their family and send their children to school,” according to Gurung. Nepal’s per capita income averages $1,000 per year or about $83 per month.

“Each tea has its own aroma, color, body, looks, taste, and distinct character. A cup of tea is not as simple as it looks if you take the time to think how it has traversed all the way up from a sapling to sipping from a cup,” said Gurung.

Related: Nepal Tea, Quality from the Himalayas (PDF)

Nepal Trade Integration Strategy (PDF)

Tea Market

Get More Value from Your Tea: BRU Maker One

+41794574278

Jacque's Organics

(647) 804-7263

Informative and encouraging article.