Pradip Baruah was born curious. He spends much of his time in the office and lab as chief advisory officer at the Tocklai Tea Research Institute (TRI) in Jorhat, Assam, but loves an adventure whenever the opportunity arises. In January he fulfilled one of his long-held dreams on a walk into the jungles of Assam where he photographed an ancient wild forest of Camellia Assamica, a species of large-leaf tea distinct from China’s Camellia Sinensis.

An avid explorer, Baruah, who has a PhD in agricultural science, has hiked the jungles that rise above the great Brahmaputra River Valley for many years, documenting various cultivars and collecting specimens used in his work at TRI.

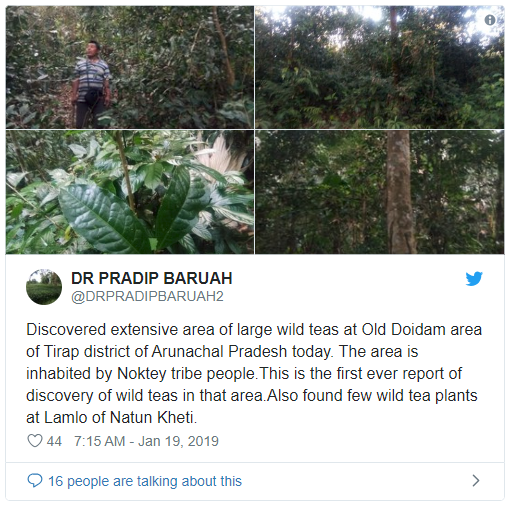

His curiosity led him to the Old Doidam area north of Myanmar, in southeastern Arunachal Pradesh. The state is India’s fifth-largest tea-producing region. There he met with members of the Noktey tribe who demonstrated how they make Khelap, the native word for tea. Noktey are one of the major tribes in the region that includes Daflas, Monpas, Adis, Akas, Apatanis, Mishmis, Nishis, Wangchu, and Sherdukpens. Tribal people still rely on tea’s medicinal properties, an awareness that dates to Neolithic times.

“It is dried in the sun and ground for storage above the fireplace. It smells very smoky and tastes bitter. They drink it from time to time,” says Baruah.

Tribal leaders later led him to an extensive area of large wild trees. “This is the first-ever report of wild trees in this area, he said. He also found a few wild trees growing near Lamlo in Natun Kheti. Baruah said that other probable areas of wild trees are Khonsa and Mishimi Hills, Miao of Arunachal Pradesh, and Mon district of Nagaland along the Indio-Myanmar border.

Baruah said that local tribesmen indicated the tea plants have existed in the wild since time immemorial. “I talked to the village elders and there is no knowledge of anyone planting here,” he said.

The discovery is significant because the international genomic study describes the origin of Camellia assamica in Assam. These tea plants could be the original Camellia assamica (Master) tea plants, which grew wild in the forests of undivided Assam during a time when the seven states of northeast India – Arunachal Pradesh, Nagaland, Tripura, Mizoram, Manipur, Meghalaya, and Assam – were under one umbrella.

He said that tea plants, locally known as “Thing Pi”, are also found to be growing wild across the mountain ranges of Manipur. “The leaves from such trees are processed locally and brewed in a typical style for domestic consumption,” he said.

“Based on the morphological characteristics, these tea plants could be the masters of the Assam tea race… further scientific study is required to ascertain the fact,” he said.

There are 82 Camellia species of which three, Camellia sinensis (var. sinensis, var. assamica, and var. lasiocalyx), are brewed as beverages. Lasiocalyx is found in Cambodia is primarily used for developing hybrids. Tea plants on Assam’s vast plantations today are mostly cross-breeds of Sinensis and the Cambodia variety, pruned low to facilitate plucking.

“Genetic studies reveal Assam tea to have a distinct genetic lineage from China tea, indicating that the origin of Assam tea is Assam itself and not introduced from China as predicted earlier,” says Baruah. However, one assamica varietal does appear to have originated in China.

A 2016 research paper on the Biodiversity of Assam and Tea presented by Baruah at the Assam Agricultural University International Conference, cited genetic studies carried out by Muditha K. Meegahakumbura that were published in a prestigious international journal. The differences in tea are likely the result of three independent domestication events from three separate regions across China and India, according to Meegahakumbura et. al., who based his conclusions on structure, PCoA, and UPGMA analyses.

Meegahakumbura concluded that unlike southern Yunnan Assam tea (found near Xishuangbanna, Pu’er City), western Yunnan Assam tea (found near Lincang, Baoshan) shares many genetic similarities with India’s C. sinensis var. assamica. Thus, western Yunnan Assam tea and Indian Assam tea both may have originated from the same parent plant in the area where southwestern China, Indo-Burma, and Tibet meet. However, as the Indian Assam tea shares no haplotypes with western Yunnan Assam tea, Indian Assam tea is likely to have originated from independent domestication. A significant proportion of samples were shown to possess genetic mixtures from different tea types, suggesting a hybrid origin for these samples, including the Cambodia type. The study revealed that Chinese C. assamica has a distinct genetic linage compared to C. assamica tea from Assam. Chinese assamica and Indian assamica were likely domesticated independently in southern Yunnan, China, and the western portion of Yunnan Province, and Assam, respectively.

Historians suggested that Assam tea had been introduced from China, but the researchers found that the short breeding history of this tea in Assam made that unlikely. According to them, if the Chinese Assam and Indian Assam teas were from the same origin, they should have been genetically much more similar. These studies further supplement the fact that the Assam type of tea originated from Assam itself and is genetically diverse from other types of tea.

Baruah said that planting materials for future quality, pest, and disease-resistant plants with unknown quality parameters with special characteristics could be discovered from these wild tea plants of Assam and northeast India.

“There is a great future of producing specialty wild tea which has a big international market,” says Baruah.

Tea Market

Get More Value from Your Tea: BRU Maker One

+41794574278

Jacque's Organics

(647) 804-7263

Pradip Baruah, son of a journalist and a distinguished tea scientist in India, has unraveled the hidden stories of Assam tea through his insatiable curiosity and vast expertise. His most notable discovery is the forgotten Senglung Tea Estate, established by India’s pioneering commercial tea planter, Maniram Dewan.