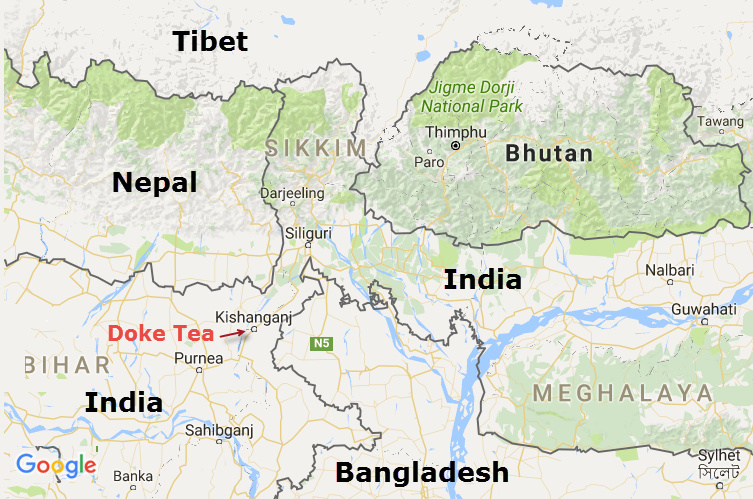

BIHAR, India

A century ago, the fabled Doke River, which descends from a Himalayan glacier to cross the hot plains of India south of Nepal, had virtually run dry, the victim of agricultural diversions that resulted in its abandonment by India’s Riverwater Navigation Department.

The surrounding land was declared no longer fit for cultivation.

The rich, loamy soil in the shadow of Darjeeling’s high-altitude gardens lay idle for a generation until the 1990s when irrigation projects were constructed. In 1998, the government, noticing the strong growth in domestic tea sales and unwilling to disrupt supplies available for export, declared this land a “non-traditional” tea-growing area. The decision caught the eye of Rajiv Lochan, then a 44-year-old tea garden manager who had spent 15 years learning his craft in Darjeeling at numerous tea gardens, including Ambootia, Phuguri, and Longview. He had returned to West Bengal in 1997 to manage Jayshree’s Dinajpur operations after three years in South India.

Lochan set about establishing a tea trading company and began buying barren tracts of land from existing landlords in Bihar. He then started rehabilitating the land and planning the appropriate water management infrastructure for both irrigation and drainage. It took 10 years to acquire and consolidate the various plots into a single garden known as Doke Tea, an organic farm along the south bank of the river.

In 2010, the course of the languishing river’s water supply was restored and waters once again filled the Doke’s banks. With water now plentiful, tea became a viable crop and soon there was an ever-increasing demand for labor. This coincided conveniently with the government’s plan to stop the exodus of laborers to Punjab. After nearly two years of considerable effort employing biodynamic principles of cultivation, the soil was ready. Lochan recruited local workers and encouraged the team managing the garden to retain their language and shamanic customs (experienced workers are free to build comfortable bungalows).

Immigrant workers from Nepal (Gorkhas) and Tibet (Khampas), and tribal people from Chota Nagpur, Orissa, and Chhattisgarh were employed as bonded laborers. Managers known as Sardars enforced tribal segregation to the extent that marriage ceremonies required the manager’s approval. Not only did the workers return to liberalized working conditions, so did the remarkable pink-colored freshwater dolphin, turtles, and even crocodiles.

“Our business philosophy is first and foremost ecologically friendly to the air, the water, the soil, the animals, and most of all, to the people who work and live on the land,” said Lochan.

Lochan initially planted clonal TV-25 and TV-26 cuttings from Naxalbari, along with TV-22 drought-resistant cultivars. Another two years passed before the young bushes were mature enough to produce their first crop. Five years after the project was undertaken, the first commercial crop reached the market. Acclaim followed as tea critics praised the tea’s flavor, awarding a Gold Star at the U.K.’s Great Taste Awards 2014.

Today, the spring flush is made into an award-winning Silver Tips white tea, which received a gold medal at the World O-CHA Tea Festival 2016 in Japan. Lochan is aided by his wife Manisha, son Vivek, and his daughter Neha; together they have refined their hand-processing techniques and developed several signature teas. These include Green Diamond green tea, Rolling Thunder oolong tea, and Black Fusion black tea. Along the way they discovered that with a more refined plucking, removing woody stems and fibers, the leaves released hints of caramel and maple, particularly in the black tea. Additionally, taking local environmental factors into consideration, modifications in the withering and oxidation steps are combined with simple techniques and tools, to gain greater control over the final outcome and consistent characteristics. Subsequent flushes are sold to other “bought leaf” factories to be made into finished tea.

Over the last 100 years, India has exported virtually all the black tea it’s produced. Doke is one of several gardens demonstrating that India is now competitive in green tea categories. Lochan’s specialty teas are largely for export, with clients in Europe, Japan, the U.S., and Canada – he even sells tea in China – but domestic demand is also increasing. In 1951, consumption per capita was 200 grams (far below the United States per capita average of 500 grams). Today there are millions of new tea drinkers. Consumption in India rose to 720 grams in 2014. In 2010, Lochan’s output was 100 kilos. He now produces 500 kilos per year and expects to reach 1,000 kilos eventually.

Lochan is Hindi, has a degree in organic chemistry, is an intrepid traveler, speaks five languages, and remains an enthusiastic student of tea production methods globally. He corresponds via social media with hundreds of growers around the world, speaking often at conferences and as a champion of smallholders.

“Worldwide, wages for tea pickers and laborers is quite low,” he observed. “To mitigate the impacts of low incomes, the education expenses of the Doke workers’ children and marriage expenses of their female child are borne by us,” he said. When asked about his long-range vision for Doke and its effects on the community, Lochan smiled and quoted a local saying, “you dig a well for quenching your thirst and then leave it for the community to drink from it forever.”

Plans are underway for an educational retreat for visitors to enjoy and learn more about tea production and appreciation. What better way than while nourishing their bodies and spirits in a serene tea garden that was raised to emerald splendor along the once dusty banks of the Doke River?

§ § §

Interested in seeing Doke Tea Estate for yourself? Meet Rajiv Lochan as well as learn about Darjeeling and Indian tea production on a 14-day Tour of India arranged by World Tea Tours, October 7–20, 2017. Add a Ceylon (Sri Lanka) pretour, Oct. 2–6. Tours led by Dan Robertson. Click for itinerary. Learn more: www.worldteatours.com

Interested in seeing Doke Tea Estate for yourself? Meet Rajiv Lochan as well as learn about Darjeeling and Indian tea production on a 14-day Tour of India arranged by World Tea Tours, October 7–20, 2017. Add a Ceylon (Sri Lanka) pretour, Oct. 2–6. Tours led by Dan Robertson. Click for itinerary. Learn more: www.worldteatours.com

Tea Market

Get More Value from Your Tea: BRU Maker One

+41794574278

Jacque's Organics

(647) 804-7263