A Tea of Their Own

Recipe

» Georgian Halva

from the cookbook, Lobio: The Vegetarian Cooking of Georgia, translated and adapted by Michael Denner

First, some context: To understand tea culture in Georgia, you have to understand Russia’s relationship to tea. The Russian aristocracy fell for tea in 1638, when ambassadors from the Golden Khanate in northwestern Mongolia gifted four pounds of green tea from China, in sixteen quarter-pound packets, to Tsar Mikhail Fyodorovich Romanov.

“You brew it,” explained Vasiliy Starkov, the Russian Empire’s ambassador to the Khanate, as Mikhail stared at the shriveled black leaves. Mikhail didn’t care for the tea — he was directed to drink it with milk — but his son, Aleksei, drank it as medicine in the 1660s. Aristocratic courts being what they are, the boyars (Russian lords) took to the brew, and by 1679, there are records of regular deliveries of tea to Russia from China. In 1696, the first Russian tea caravan set forth from Moscow to Beijing, and so it all began…

Tea was an expensive habit in European Russia: caravans took a year and a half, sometimes longer, to travel from China to Moscow, via Manchuria and Mongolia, on camels, steamboats, sleds and wagons. In the eighteenth century, only rich people in cities drank tea; it was unknown in the Russian hinterlands except near Baikal, in far-eastern Siberia, and in parts of Central Asia which were culturally-connected to China, and all drank tea from “time immemorial.” By the middle of the nineteenth century, though, tea was common: Imports increased tenfold from 1810 to 1860. By 1917, immediately before the Bolshevik Revolution, the annual consumption of tea in the Russian Empire was 132 million pounds (60 million kilos) annum.

And here is where Georgia enters the picture. Avoiding some geopolitical landmines, I’ll stick with the facts: By the beginning of the nineteenth century, Georgia had been incorporated into the Russian Empire. On a map, you’ll quickly conclude that Georgia is way south of Russia. Batumi is about as far south in Georgia as you can go — on the Black Sea near the border with Turkey — at approximately 41-degrees North, roughly parallel with Beijing. The south of Georgia is rimmed by the Black Sea and contains ranges in the Minor Caucasus chain. The steep mountains and sea protect the region from cold, southward European winter fronts. The average winter temperature in Batumi is around 45-degrees F. Climatically, parts of the south are temperate rainforests: The rainiest point in Europe is just south of Batumi in the Mtirala National Park.

Georgia’s climate corresponds very closely to tea regions in India, Kenya, and China. The perfect place to grow tea bushes!

Wrong. It was, apparently, a terrible place to cultivate tea.

During the first decades of the nineteenth century, the Russians and Georgians planted large tracts of land, having stolen tea seeds and bushes from China (and later India). They chose the warm valleys of Ajara and Guria. Growing tea for the Russian Empire there avoided the costly transportation of tea across Siberia, and dealing with China, with whom Russia had long-standing territorial disputes. Like the British Empire’s tea trade with India, Russia sought a patriotic product of the empire, a tea of their own.

Tea Cultivation Takes Root

Many sought to establish a tea dynasty in Georgia, and failed until a tea merchant named Popov invited the Cantonese (Guangdong) tea expert, Liu Junzhou (刘峻周) and ten of his countrymen, to Chakva, just north of Batumi, in 1893. Liu brought 1,000 kg of tea seeds and 150,000 saplings from China. By 1896 Liu brewed the first cup of tea from the plantation, and by 1900 he had won, in Paris, a gold medal inscribed: “Best Tea in the World.” (Most Soviet and Georgian histories of tea cultivation in Georgia omit Liu Junzhou’s many contributions, and instead dwell on Popov’s investments and dedication to the project.)

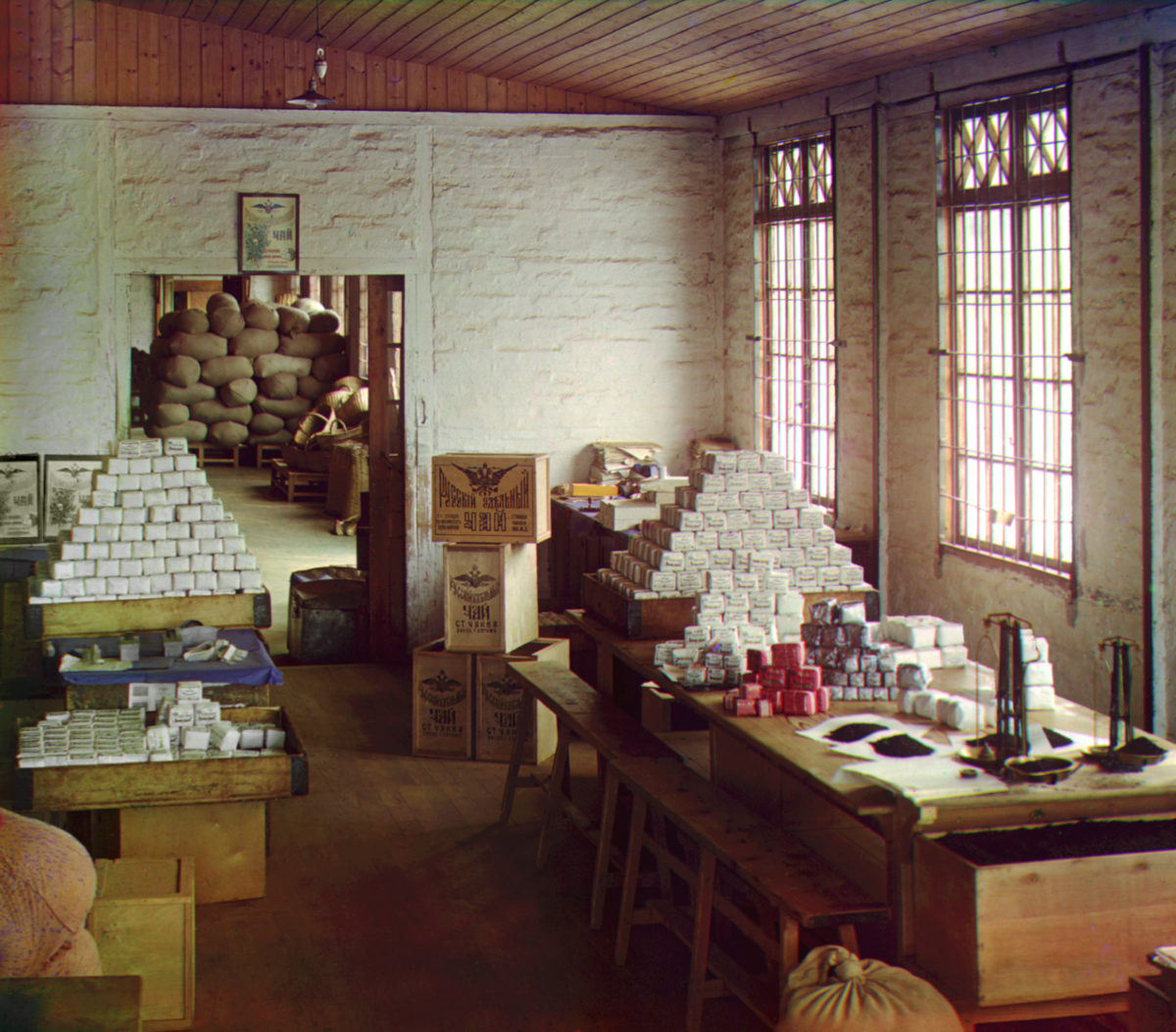

Fascinatingly, there are color photographs of that plantation in Chakva, and of Liu himself, taken by Sergey Mikhaylovich Prokudin-Gorsky (“Photographer of the Tsar”) using his fancy, four-color, high-tech camera.

Georgia became, at the threshold of the twentieth century, the only European territory where tea was grown commercially. The success was modest. In 1917, only about a thousand hectares (less than four square miles) of land were devoted to tea cultivation. Harold Mann, noted tea expert and Scientific Officer for the Indian Tea Association from 1900-1907, remarked in 1915 that “the tea industry in Russia seems to be a plaything for the tsar and a handful of rich merchants.” (Mann would visit the Zugdidi region in the early 1930s and declare wrongly that Georgia was unfit for tea cultivation.)

The Soviet Empire

After the Bolshevik Revolution and the subsequent founding of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, Georgia was absorbed into the Soviet Union, mostly against its will, as the Transcaucasian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic (TSFSR). The TSFSR was dismantled in 1936 and Joseph Stalin created three separate “national” (ethno-linguistic) republics: Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia.

Georgia, and especially Georgian agricultural products like mandarin oranges, tomatoes, and tea, were held in the highest esteem in the Soviet Union, and for that matter, in the entirety of what used to be called “the second world,” including places like Mongolia, Yugoslavia, East Germany, Ukraine, etc. This second world formed, at the end of World War II, one of the largest global markets, decades before the European Union.

In this “second” world, there was paltry private property, and few market forces were at play. Instead of being bought and sold on the free market, goods and services were “producer goods.” The Soviets “rationalized” the means of production and consumption, which meant some guy in an office building in Moscow decided, every five years, how many units of a certain good would be produced, how much it would be sold for, and where it would be sold. It was a “command economy” that worked sometimes, but not often.

This second world collapsed, with little warning, and certainly as a surprise to 99% of the population, at the end of December 1991. Georgia, really for the first time in its entire long history became an independent, sovereign, democratic country.

And all hell broke loose.

In many ways the Soviet Union was truly good for the Georgian tea industry. Tea cultivation in Georgia became, during the Soviet period, a state matter, and a very important one at that.

When Joseph Stalin declared, in the mid 1920s, his “socialism in one country” theory, he set the USSR on a path towards autarky, in other words, national self-sufficiency: The USSR developed its economy in such a way that it would rely on no other country for goods. Georgia, as the only subtropical agricultural area in the USSR, took pride of place in this autarkic system. Tea and mandarin oranges were its main export to the USSR and its “internal empire” of 15 constituent republics. The importance of Georgia’s tea industry only increased after the Chinese-Soviet split in the early 1950s.

By 1950, Georgian tea supplied half the world. Every Soviet citizen of a certain age fondly recalls Georgian tea as one of the few “luxury items” regularly available to the average Soviet citizen. At the time consumer items of any sort were a luxury in the Soviet Union. Georgian teas came in metal boxes, which became storage boxes useful for bolts, worthless rubles, and precious cosmetics. When I moved into my first apartment in Moscow, where the recent occupant had just passed away in his 70s, I found the shelf above the tiny refrigerator overflowing with a lifetime’s collection of Georgian tea tins. It was my first encounter with Georgian tea!

Throughout the post-war period, large bricks of compressed black and green tea, made from the seeds and leftover leaf bits on the drying belt, were marked for use in Siberia for “hunting and expeditions.” The bricks were, in fact, sent to the state penal colonies (Gulags) and far flung military camps. Alexander Solzhenitsyn, writing about his own experiences in the gulag in Kazakhstan in the 1950s, always mentioned the two “luxury” goods that prisoners received: tea and tobacco. He credits “tea mushroom” (a sort of basic kombucha) made from the guards’ leftover cold tea for saving his life. Convicts in the Soviet Union would pool their tea bricks and make a special slurry of tea, a super-potent tea decoction jokingly called chifir. (The word is likely a portmanteau of “tea” and “kefir,” a fermented milk beverage.) Georgian tea was considered the best tea for making chifir. In the absence of vodka, Georgian chifir offered *kaif*, got you a little high. In the absence of fruits and vegetables, the not inconsiderable vitamin content of tea also made the difference between life and death in the penal camps.

The Soviet Union lied about everything, pervasively, often pointlessly. Any and all statistics, numbers, records, plans, official reports, accounts, news, documents, affidavits, etc. should be treated with skepticism, and perhaps disregarded automatically. That said, the numbers for tea production are impressive: In 1921, Georgia produced 550 (presumably metric) tons of tea leaf. By 1966, it produced 226,000 tons. The Black Sea region of Georgia became the “tea pantry” for a vast empire that stretched from Berlin to the Pacific Ocean. Guria, a region in Georgia, became known as the “tea Donbas,” i.e., like the Donetsk Basin (Donbas) in eastern Ukraine where coal was mined, Guria had become an industrial powerhouse of tea production.

In a way, the Soviet century was the golden age for tea in Georgia. Soviet bureaucrats dreamed of covering the otherwise “empty” mountainsides of Georgia with tea: “Not a single inch of these lands will remain bare,” predicted one early “tea influencer.” Moscow bureaucrats demanded unachievable goals. Research institutes were dedicated to the study of tea cultivation and the production. Vast factories were built and equipped with the best machines Soviet engineers could devise. Massive tea plantations were created, planted, harvested, and processed through the collective farm (kolkhoz) system. Workers were trained in the art of tea harvesting and processing (drying, curling, fermenting, heating, etc.) The tea was sent for final sorting, boxing, and shipping to Tbilisi, Georgia’s capital, and from there, the world. In 60 years tea cultivation in Georgia went from the “tsar’s plaything” to a professional and successful tea industry. From 1917 to 1980, the amount of land devoted to tea bushes increased about 100 times, from less than 2,500 acres (1,000 hectares) to almost 250,000 acres (100,000 hectares equivalent to an expansion from 4 square miles to 375 square miles).

Collapse

And then, the Soviet Union collapsed at the end of 1991… And with it went the tea industry in Georgia.

Reading various articles and accounts of the period, there is plenty of blame to go around for the failure of tea in Georgia. The collapse was ultimately due to Soviet priorities: At the end of the Brezhnev years, it became fashionable to rail against “old-fashioned” things like manual picking of tea bushes. (Earlier in the Soviet period, the manual labor on tea plantations and tea pickers were romanticized: There’s even a famous Soviet/Georgian film called Dragonfly, a production film about the virtuous, labor life on a Georgian tea farm.)

Despite the fact that the Chinese grow and harvest tea largely the same way now as they did a thousand years ago, the Soviets decided to modernize the process: First, they increased their use of artificial fertilizers, and then engineered monstrous “picking machines” that would hack off the top foot of tea plants. Forget the “flush,” the newest growth carefully plucked by expert tea pickers. The machines bellied right up to the factory and “leaves” were dumped on a conveyor belt. Big bricks of low-quality tea were processed and spat out. The Soviets, who had become accustomed to some pretty good tea from Georgia, switched to Lipton. By the end of the eighties, there was an absurd “tea shortage” in the Soviet Union: When I first arrived in St. Petersburg in 1991, everyone asked me to bring them yellow boxes of Lipton tea.

A cultural gap explains, in part, the collapse of the tea industry in Georgia. Georgians themselves don’t drink much tea: Georgia is justly famous for its “natural” wines, and considers itself the “birthplace of wine.” (The Georgian word hvino, goes the thinking, produced all the Indoeuropean version of the word “wine.”) The Georgian national drink is wine, not tea. As the Soviet Union fell apart under Gorbachev, the Georgians saw little reason to continue to provide the Russians with “their” tea.

The transition from its Soviet experience to the “world market” was difficult for Georgia. For much of the twentieth century, Georgia provided agricultural products — and little else — to the Soviet Union and its satellite states; in return, Georgia imported virtually everything else, notably machinery, electricity, and petrochemical fuels like natural gas and gasoline. And, suddenly and without much notice, that economic entanglement ended. Georgia quickly descended into economic and civil chaos for the better part of two decades. During this period, the tea plantations were ignored — whom were they going to export to? The Soviet Union’s emphasis on mechanization and commodification had destroyed the Georgian “brand” of tea.

Soon after the collapse, a Georgian corporation assumed control of the tea plantations in the area, promising to revitalize them; instead, the machinery was sold to Turkey and the fields were abandoned. The tea plantations themselves reverted back to what they had been before they were covered with tea plants: Nature, that is to say, deciduous forests, hillside and mountain flora, whatever had been there before the Soviets decided to extract value out of “every square inch” of Georgian land. Tea production in Georgia had all but ended by the mid-1990s. You could find locally-grown tea in the markets in Guria and Ajara, but it was grown, picked, and processed more as a curiosity, a throwback to the Soviet era.

A Tea Renaissance

The last five years has seen a resurgence in tea production in Georgia, a rediscovery of the heritage of tea cultivation in the twentieth century. The reasons for this renaissance are many, but chiefly it’s been a result of economic and cultural changes. The World Bank forecasts a growth rate around 5% in Georgia for the foreseeable future, about double the rate in Europe and North America. Moreover, reforms in the private sector have made it easier to do business, so the country’s international ratings on governance and the investment climate have soared. Finally, there’s been a notable embrace of Georgia’s heritage as an agricultural center of Europe: Georgian wines, which were virtually unknown in Europe and North America 10 years ago, are now all the rage. Georgian cuisine, again virtually unknown a few years ago is, for the first time, enjoying fame outside of the former USSR. Perhaps predictably, Georgian-grown tea has reemerged. Can Georgian tea be far behind wine and cuisine in gaining the notice of the world?

In July 2019, I visited several tea plantations in the south of Georgia, not far from Batumi, in the states of Guria and Ajara, where tea cultivation in Georgia originated over a century ago.

In Guria, not far from Baghdadi (where the Soviet poet Vladimir Mayakovsky was born), Davit Teneshvili told me that, when he was a child in the 1980s, in a village not far away from his house, there was a large factory that employed 600 Georgians processing and packaging 200 tons of tea every workday. (The factory worked seasonally, not every day.) Davit’s parents worked on the tea plantation and owned a house on the “collective farm” where the tea plants grew and were picked.

His family home is now a maze of tea plants, citrus trees, maize, fruit trees, grape arbors, chickens and cows. He gestured at one smallish, two-hectare plot of tea bushes separate from the much larger main plantation: This smaller garden was owned by his family and they could sell the tea they raised to the factory for cash (otherwise an impossibility in the USSR).

Davit’s farm and plantation is a model of productive efficiency and order, but it wasn’t always the case. He remembers a time 22 years ago, clearly painful for him, when he asked his wife for a cup of tea one afternoon. “There is no tea left.” (No tea in Guria is gobstopping, like no coals in New Castle or no steel in Pittsburg.) For a decade, he and his family lived on subsistence farming and odd jobs, without reliable electricity. They used a generator powered by the stream that runs through his property. (Georgia is a country of rivers; there are 25,000 rivers in the countries 25,000 mile territory.)

Davit has spent the last few years recovering the tea fields that lay under chestnut trees, beech trees, and weeds, revealing the fields that had survived, none the worse, decades of disregard. Georgians largely lack machinery, so much of the work of recovering the tea fields has been done by hand, field by field, row by row, bush by bush. They cut the bushes back to the ground and left them alone for three years to grow back to harvesting size. Georgians lack the money for investing in artificial pesticides and fertilizers; and proudly claim that their product is “ecologically pure.” Camellia plants are tough and need little in the way of inputs to produce high-quality leaf.

The trees that grew in the fields over the last 30 years are hard to remove, so instead of cutting out the chestnut and walnut trees that sprout everywhere in Georgia forests (and following a longstanding tradition observed by grape growers across the country), Davit has left them alone. It turns out, he tells me, that this is great for tea bushes: The bushes appreciate the shade, the birds that nest in the trees are “natural pesticides.”

His tea plantation, terraced into a warm valley, can be harvested 10 months of the year by locals, many of whose families worked on the old Soviet kolkhoz decades ago.

In the absence of any central mechanized factory to process the harvest, Davit has had to dry the leaves, until they become “tender” on large wooden racks and jute mesh, in the shade.

His first curler — tea leaves are curled after they’re dried a bit; it helps the fermentation process — was made by hand, with grooves and paddles carved from walnut wood. It was powered by the generator in the river, beginning in the 1990s — unsurprisingly with something as mechanically simple as this roller, it works perfectly well today powered by electrical current. Davit, demonstrating it, remarked: “From this machine reemerged tea in Georgia.”

The curler has just been replaced by a metal rolling machine, imported from China. It cost $3,000, a fortune for someone in Georgia, especially given the undeveloped nature of the tea trade there. He hasn’t used it yet, because the “museum piece” outside still does the job.

Davit has electric heaters now — they look like large metal boxes on wheels — but he still prefers the old-school approach: A sealed and insulated room, an antique stove covered in firebricks, fired with trees and branches from the cleared tea fields, dragged to the workshed. Carbon neutral, I remarked. Much cheaper, he replied. Electricity in Georgia is very expensive. Wood is free. The stove quickly brings the room to around 200-degrees F. The leaves spend a short time here to stop the fermentation.

Davit sorts the tea by hand, and packages it for eventual sale. It looks as though he processes the finest, “tippiest” growth.

Davit has a perfect tea tasting “room” on his porch, outside his home. Like all Georgian hosts, he treats his guests like royalty, and the tea tasting ends with a few glasses of turbid, delicious homemade wine. The tea I tried was excellent, if generic in its flavor profile: Earthy, fruity, medium body. This “tea forward” tea (it tastes classic to me, like the tea you want to drink in the middle of the afternoon, no sugar, no milk) makes perfect sense given Davit’s market in Georgia. Tea is only ever as good as the leaf that’s picked!

The second plantation I visited is owned by Levani Tskipurishvili, who is reestablishing tea plantations about 2,000 feet up in the mountains above Kutaisi, not far from Tkibuli. Unlike Davit, Levani grows tea bushes but does not yet process the leaf. In fact, the fields are just recently coming into maturity after he cut back the plants a few years ago. Also unlike Davit, Levani’s fields are so high in the mountains and the climate is so cool and steady that these fields can only be harvested only three times during summer.

I don’t know this for sure, and I doubt even Levani knows, but their location and appearance suggest that these bushes are the hybridized offspring of Indian and Chinese tea plants: The Soviets developed a dozen or so hybrids of *C. sinensis*, breeding the Chinese small leaf tea and Assam type tea and hoping to develop a cold-hardy tea bush that could survive Russian winters, and thus expand tea cultivation above the 45th parallel. Several of the hybrids proved astonishingly hardy, surviving prolonged periods of sub-zero temperatures and still producing satisfactory tea each season. (The world’s northernmost tea plantations were in Krasnodar, Russia. I visited them in the early 1990s, when they still functioned. To my knowledge, tea is no longer grown there.)

His furthest plantation is all but inaccessible: First we drove up the side of a mountain in Levani’s truck. When we reached a point on the road when the path became too steep and rutted for the truck, we were picked up by one of Levani’s managers in a German jeep from WWII. The jeep was little more than seats bolted to a frame bolted to wheels connected by iron axles to a low-gear, high torque gas engine. We didn’t so much climb the mountainside as creep up it, foot by foot:

Like Davit, Levani by necessity practices organic growing: There’s no money for fertilizers and no need this high up, in fields that have lain, willy-nilly, fallow for decades. The natural processes that provide a forest with all the necessary nutrients has enriched and fortified the soils where Levani’s *C. sinensis* grows. He’s intentionally left the useful trees growing amidst the tea plants.

Over tea, sitting in the shade of a chestnut tree, we chatted about the vicissitudes of tea culture in Georgia, about the remarkable heartiness of the tea bush. He told stories about the Soviet days, when orders from Moscow trickled down to Georgia’s southern reaches, then slowly wound their way up the mountains of Guria and reached the tea plantations. The Soviets knew how to build industries quickly and effectively, Levani acknowledged, but they didn’t understand Georgia. We nibbled on the leaves of ekala, the Georgian word for sarsaparilla (or smilax): It grows everywhere in the Guria. It’s tasty and prolific, and it’s full of minerals and vitamins. At some point, the Soviet bureaucrats in Moscow directed the Georgians to flatten forests and grow sarsaparilla for export. The Georgians nodded, acquiesced, wrote memos… and then sent their kids into the woods to harvest the abundant ekala growing wild. They sent the leaves north to Moscow, but nothing much came of it, and the Soviets soon forgot their orders.

Decades ago, the Soviets built a tea empire: They dreamed one day of converting all of southern Georgia into a tea factory, making a “tea Donbas” of the territory. The USSR disappeared one snowy Moscow night, and these dreams of transforming the world came to naught.

Empires come and go, but tea is, apparently, forever.

Tea in Georgia

- New source: Not China, not India. It’s the only tea grown on a commercial scale on the European mainland.

- Production peaked in the mid 1980s at 150,000 metric tons; but collapsed during the 1990s, because of USSR agricultural policies.

- Lipton, imported from the USA, was the most popular tea brand in the USSR in 1991, when the Soviet Union suddenly collapsed and the 15 Soviet republics (including Georgia) became independent countries.

- Georgia is an ideal place for tea tourism: Guests are “God’s gift” in Georgia, and the tea, food, and wine is incomparable.

- Much of the tea from Georgia, and all the tea produced on the plantations that I visited, is “clean tea”: Totally organic, practically wild tea, bird and beast friendly.

- Understanding the fate of tea in Georgia tells the story of Georgia from the beginning of the nineteenth century, through the establishment and collapse of the USSR, and of the renewed and exciting Georgia today.

- Emerging tea and opportunity: 10 years ago, no one knew they produced wine in Georgia, now it’s the darling of the wine business. The same is true now for tea. Few people know that tea is produced in Georgia, but in ten years…

That was very interesting. I learned a lot by reading this article

Having the freedom to be creative with all this historic background makes for some interesting years ahead for Georgian tea. I know the Indians have neem trees in their tea plantation fields while Liptons in Kenyan leaves natural corridors of native trees inviting all sorts of wondrous creatures to live nearby…makes for better tea tourism too. In Taiwan, when bushes were young or recovering from a severe pruning, they grew ginger in between the rows. They also used peanut shells as mulch in between the rows . What the tea world can teach each other is inspiring!

What makes Georgian tea valuable is that it provides an opportunity for ideas that go beyond the mere fact that tea can be produced in Europe like in the East. Wine has a history of 8,000 years, and Georgia has been mentioned as its place of origin, and tea has a history of 4,700 years. Until now, much of the history of tea has been recognized in terms of cultivated botany. If we are interested in experience, research can focus on Georgia’s potential as a place of origin. This article provides an opportunity to discover new facts about tea, which is acknowledged to have been discovered later than wine. In that respect, this article is valuable, and editor Bolton’s sense stands out. Tea sufficiently meets the stage of tea culture. Attempts to solve social problems and prepare for a future human society through tea culture have emerged through numerous academic activities. As a result, Tsaiology was published in 1826. However, it was not sufficient to establish a logical and objective knowledge system of tea and did not reach the point of developing a discipline unit. In 2000, 224 various disciplines related to tea and tea culture were developed. We succeeded in developing the experience in tea culture to the stages of recognition – fact checking – information preparation – knowledge development – theory establishment – a discipline. As a result, it was concluded that the nature of tea-related studies is a complex of diverse and heterogeneous tea-derived phenomena. Tea culture is divided into six categories: humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences, art and interdisciplinary studies. On that basis, it became Teaics and was listed in the Routledge Handbook of tea tourism index in 2023. Tea has reached the stage of discipline. Teaic antropology, a discipline belonging to Teaics, is expected to further discover the value of Georgia’s tea cultures y3973@naver.com /Brian Park Korea