Sixteenth century Japanese tea men who immersed themselves in chanoyu, or “art of tea,” can point the way to enriching the experience of modern tea aficionados.

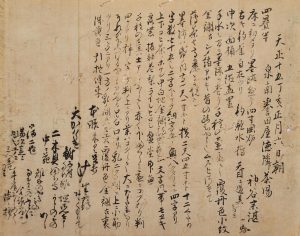

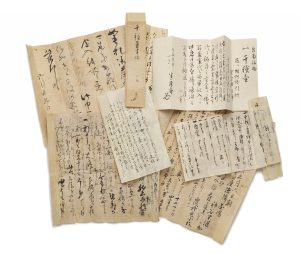

Those discerning Japanese merchants, scholars and rulers participated in tea rituals and recorded detailed observations in their diaries, chronicling their appreciation not only of the matcha itself but of the objects used in the drinking of the tea as well.

“The diaries show how much they paid attention to all these things and by paying attention not only to the taste of the tea, but to the vessel it’s drunk from, how it increased the enjoyment,” says Andrew Watsky, a professor of Japanese art history at Princeton University.

“Looking at and appreciating objects’ shape, size and so on was part of the pleasure of tea. They took this very seriously,” Watsky says. “It’s not just pulling out any old mug. It’s paying attention and being very aware and alert to not just the tea itself, but to the vessel you drink it from.

“I’m talking about something based on the experience of the moment, a sensory experience. It’s experiencing the now and enjoying the moment. It’s holding that bowl in your hand,” he says, adding, “personally, I pay a lot of attention to what I drink tea from.”

A Revered Object

Particularly fine items used in these Japanese tea rituals were designated as meibutsu, or revered objects, by the tea men. Chigusa is a meibutsu tea jar and one of the most famous of several hundred antique ceramic storages jars still in existence.

Watsky has spent years studying Chigusa and myriad tea diaries’ entries about it. He and Louise Cort, curator of ceramics at the Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, in Washington, D.C., are editors of the book “Chigusa and the Art of Tea.” He was co-curator of the Chigusa exhibit at the Princeton University Art Museum last year.

Those tea diaries recorded descriptions of Chigusa’s physical attributes and accessories that allow contemporary scholars to see the jar through the writers’ eyes, notes Watsky. The diaries detailed its size, shape, appearance and pedigree. They even noted characteristics like glaze texture and blisters from the kiln’s heat.

The tea men’s diaries described Chigusa’s use in the kuchikiri or “the cutting of the mouth,” the annual ritual of cutting open the paper seal of the jar and the grinding and serving of the new tea.

Fresh tea was picked in the spring then stored in a ceramic jar in a cool place. In the autumn, the removal of the wooden lid and cutting of the paper seal marked the opening of the jar for the first time after it had been stored through the hot summer months.

In the book “Chigusa and the Art of Tea” tea scientist Omori Masahi explores how this process of storing the tea in jars in a cool place during the hot, humid Japanese summers improved its taste.

When Masahi asked tea drinkers to compare un-aged new tea with aged “autumn new tea” they reported that “the un-aged new tea somehow attacked the tongue, while the autumn new tea did not.”

Compared to the un-aged tea, “autumn new tea had approximately 10 percent less polyphenol, caffeine and amino acids. Unlike new tea, the autumn new tea appeared blackish and the oxalic acid and the DDPH radical-scavenging activity had decreased approximately 10 percent.”

As Watsky puts it, in lay terms: “It removed some of the bitterness. The tea was rounder in the mouth.”

In studying the documents about Chigusa and other jars, Watsky learned that the 16th century tea men even found that tea stored in different jars developed different tastes.

“They might talk about how the tea stored in a certain jar is delicious, wonderful. In a way they were saying that part of the greatness of a really great tea jar was that it actually improved the flavor of the tea.”

Lessons from Chigusa and Chanoyu

Modern connoisseurs can learn from Chigusa and chanoyu.

They don’t need to go out and buy a tea jar, although Watsky comments that he has thought of it. What they can learn, he says, are the benefits of taking care of tea to get the most out of it.

“It matters where you get the tea, how you store it, that you make sure it’s properly prepared,” says Watsky, a confirmed matcha drinker who buys all his tea in Japan.

“I talk to people at the shops I go to. I trust them; I’ve developed relationships with them. If I go to a new place I ask them to tell me what the differences in the teas are.”

“It’s almost as if you’re buying a bottle of wine. Take the time to get to know where the tea is from and let people who know share their knowledge.”

Meet Chigusa

Please meet Chigusa, the object of so much fascination. At first glance, the jar looks like an ordinary old storage container. Chigusa is old — more than 700 years old — and over the course of those centuries it has become one of the most revered objects of Japan’s chanoyu, or “art of tea.”

From the extensive records kept by Japanese tea men, scholars today know that Chigusa originated as one of countless utilitarian ceramics made in southern China during the 13th or 14th century and was shipped to Japan as a container for a commercial product.

In Japan, Chigusa, like other Chinese storage jars, was endowed with special status, and over the years it became a highly desirable antique. Only a few hundred other tea storage jars survive and fewer still are accompanied by such a wealth of artifacts and documentation.

Japanese tea enthusiasts awarded each jar its own name, often tied to poetry or literature, as a sign of respect and reverence. The name Chigusa means “abundance of varieties,” “abundance of plants” or “myriad flowers.” Since Chigusa has its own distinctive name, scholars have been able to trace its story precisely to the present day.

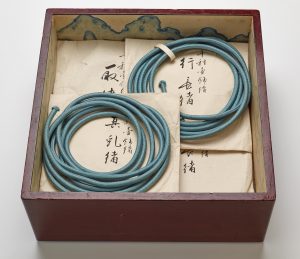

Believed to have been made during the Yuan dynasty, Chigusa is colored with a mottled amber glaze with four lugs on it shoulder and a cylindrical neck with a rolled lip sealed by a silk cover and secured with cord.

Tea men noted Chigusa’s characteristics and recorded minute observations in their tea diaries. One eyewitness, who saw the jar at a gathering in 1586, admired its large size (16.5 inches tall) and the reddish color of the clay.

“Tea men looked at Chigusa and found beauty even in its flaws, elevating it from a simple tea jar to how we know it today,” says Louis Allison Cort, curator for ceramics at the Smithsonian Institution’s Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery. “This ability to value imperfections in objects made by the human hand is one of the great contributions of Japanese tea culture to the world.”

In the 15th century, participants in Japanese tea ceremonies were impressed “by the quantity of objects,” she says. But in the 16th century – the high point of chanoyu — the emphasis was on the harmony of the objects within the group.

“There was a combination of precious and easily available objects and the contract of highly different materials. It was a powerful aesthetic experience for guests” at tea gatherings, Cort says.

The jar bears four ciphers written in lacquer on its base. The oldest is attributed to Noami (1397-1471), a painter and professional connoisseur for the Ashikaga shogun. According to researchers, this suggests the possibility, otherwise unrecorded, that the jar circulated among owners close to the Ashikaga government. The next oldest cipher is that of Torii Insetsu (1448-1517) an important tea connoisseur and collector in the international trading city of Sakai, known for innovative tea activity. The next owner to inscribe his cipher was another Sakai tea enthusiast, Ju Soho, who hosted a tea in the new year of 1573 for guests, including the esteemed tea master Sen no Rikyu (1522-91).

The Smithsonian Institution acquired Chigusa at auction in 2009. The famous tea jar had a brief U.S. tour and is now in storage, waiting to be exhibited at the Freer Gallery after renovation there is completed some time next year.