‘A Nice Cup of Tea’ for the 21st Century

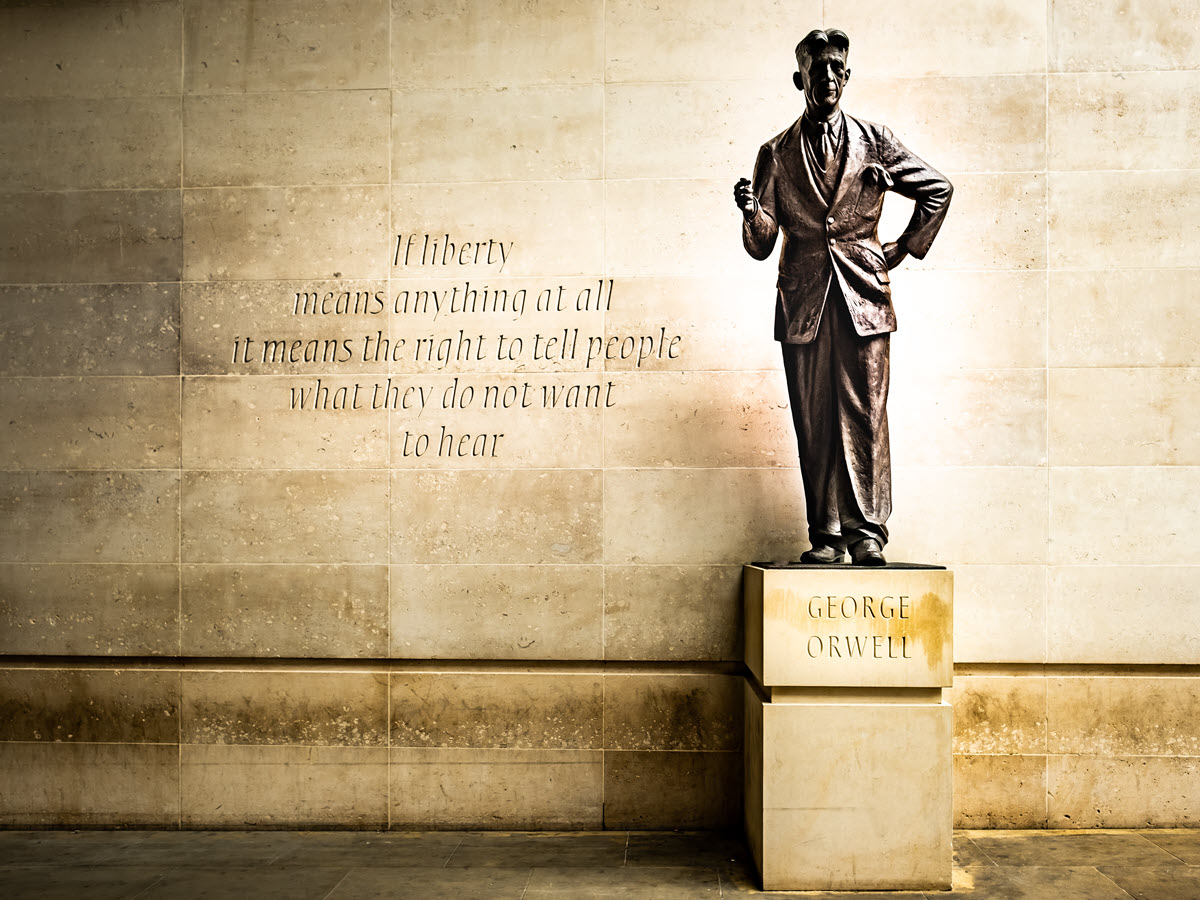

George Orwell was right: tea is the subject of violent disputes. We’ll never settle such disputes, but one obvious way to diffuse them is to drink tea itself. Infuse to diffuse.

Its virtues notwithstanding, Orwell’s classic essay ‘A Nice Cup of Tea’ needs an update. Published in the London Evening Standard in January 1946, Orwell writes: “When I look through my own recipe for the perfect cup of tea, I find no fewer than 11 rules” for preparation. His assertion that “every one of the 11 I regard as golden” helped to codify the comforting ritual of making black tea for a war-weary nation.

Its virtues notwithstanding, Orwell’s classic essay ‘A Nice Cup of Tea’ needs an update. Published in the London Evening Standard in January 1946, Orwell writes: “When I look through my own recipe for the perfect cup of tea, I find no fewer than 11 rules” for preparation. His assertion that “every one of the 11 I regard as golden” helped to codify the comforting ritual of making black tea for a war-weary nation.

Orwell drank many different teas, yet his first rule exclusively sings the praises of Indian or Sri Lankan black tea because not much else was available at the time. During 14 years of rationing, there were acute shortages of the most common goods ̶̶ such as tea ̶̶ that we take for granted. Rationing in Britain continued until 1954, well after European hostilities ceased in May 1945.

Orwell insists that you should only brew tea in a ceramic pot and that you should pour your tea first, milk second. He was speaking to a particular time and place, just as my suggestions below reflect my own experience of the world of tea in Australia in the 21st century. Tea is a rich and varied world of aromas and tastes, so in light of that fact, let’s return the spotlight to some of Orwell’s ideas on tea.

What’s your tea type?

China produces, in varying quantities, all six tea types. Green and oolong are the most commonly exported; yellow tea is the rarest. Japan produces sencha mainly for domestic consumption with rare styles that top the highest priced Chinese greens. India and Sri Lanka are known for their black teas, but reading Orwell, you’d think that tea begins and ends there. While subcontinental black teas are some of the finest, Chinese black tea also uplifts the body and soul: I can personally attest to that. In China’s southwest, black tea from Yunnan can recall malt and cocoa when brewed at around 90 degrees Celsius. (Orwell was wrong to say that the water has to be boiling.)

And while, yes, ceramics are trusted companions to tea leaves, they’re not the only way. ‘You eat with your eyes,’ someone once said. Well, you drink with your eyes too. It’s a feast for the eyes if you can brew in a glass teapot and watch the precious leaves swirl around as the hot water hits them and unfurl over the next few minutes.

Strangely enough, Orwell did not suggest any steeping times. With black tea, how many minutes is up to you. Aim for at least two minutes if brewing Western style. The longer you wait, the stronger the flavor (up to the 5-minute mark); you want the tea to be nice and warm, not scalding hot. On the other hand, steeping Chinese teas are a matter of seconds rather than minutes, demanding a quick pour of small quantities with each steep that follows a little longer than the previous. The key is to be generous: use a fistful of leaves in at least 200 milliliters of water. Adjust to taste.

No milk needed

I’m afraid I have to disagree with Orwell most violently on the need to add milk. Don’t put milk in your tea, not even black tea. Just don’t. Although I grew up drinking tea this way and remember milk first / tea first debates at home, I can now confidently say that milk spoils the tea. So leave the milk out; I insist on this as adamantly as Orwell insisted that you shouldn’t put sugar in your tea (a point on which I agree with him completely). If the tea is good enough, it should get your taste buds singing on its own.

Tea is more than just steep times and the materials and vessels you use: it also encourages you to be present in the moment. In Japan, there’s a pithy saying for that: Ichi go ichi e, which means ‘savour the moment, because it will only come once.’

Greens also make a nice cup

In his essay, Orwell had nothing whatsoever to say about green tea. In Japan, green tea reigned supreme but political tensions and sanctions curtailed trade with Britain through the 1930s. Green tea was not available in 1940s Britain; China was in a state of civil war and wasn’t exporting tea, and Japan was newly occupied and had barely started picking up the rubble of wartime defeat. In our time, green tea is served in every Chinese restaurant from Melbourne to Marrakesh. So here are a few points worth noting on the subject.

As any green tea lover should know, its preparation does demand some precision, or you risk ending up with a bitter, undrinkable decoction that you will throw into the kitchen sink in frustration. Remember to start with good-quality leaves. And don’t over-brew them. A one-minute steep is a good guide for sencha and genmaicha, using five grams per 200 ml. Allow the umami to develop fully. Use filtered water, and don’t scald the leaves: brew at 60 to 65 degrees Celsius for sencha or 90 degrees for genmaicha. Genmaicha makes a refreshing cold brew on a hot summer’s day.

It’d be remiss not to mention the wonders of hojicha, a wonderful concoction of roasted stems and leaves. Twenty seconds is all it takes (five grams per 400 ml) to brew a pot of hojicha with enough character to hold an audience captive. Think warm, inviting aromas, toasty brown liquor, a thin layer of froth, and a barley-like taste.

Infinitely oolong

The world outside East Asia has finally woken up to the almost infinite variety of tastes and aromas that tea offers and oolong tea is nothing if not complex and varied. Oolong can be light-roasted, medium-roasted, heavy-roasted, floral, creamy, sweet, or big on minerality.

On the spectrum of tea processing, oolong tea lies between black and green. Tea lovers wax lyrical about oolong. A big reason, I believe, is that it combines the depth of flavor of black tea with the delicacy of green. Steeping the same leaves at least three times is normal; nine or ten steeps are not uncommon. If the price of higher-grade oolongs is a concern, remember that they can be brewed multiple times. Suddenly these teas are quite economical. For all these reasons and more, oolong is among the most prized tea on the planet.

Tea drinking has evolved in the 75 years since Orwell’s essay was first published. The variety of teas available today would likely astonish Orwell and certainly would have astonished his Evening Standard readers. The process of discovering what a great pot of tea means to you can and should be more nuanced and wide-ranging than it was in Orwell’s time.

And that’s a very good thing.

an appropriate few words: infuse to diffuse. Now more than ever.

True.