Some studies have identified 131 pesticides in tea (Zhu, 2019); others have identified up to 400 (Ly, 2020).

Many tea drinkers assume pesticides make tea somewhat unsafe to drink.

Tea drinkers invested in the health benefits of tea are among the wariest of pesticides in tea and are often concerned with pesticide residue in tea.

The questions on many tea drinkers’ minds are:

- “Are there pesticides in tea?”, and

- “Are pesticides in tea dangerous?”

This post gives you a clear focus on facts (rather than vague impressions).

Media Coverage of Pesticides in Tea

Media coverage of pesticides in tea can stray into sensationalism.

Savvy media outlets often use headlines that evoke fear and curiosity; evoking these two emotions increases an article’s click-through rate (CTR). While such headlines may lead visitors to a media outlet’s article, they often inspire misunderstanding.

Consider these three headlines:

- “Most Popular Tea Bags Contain Illegal Amounts of Pesticides. Avoid These Brands At All Costs.”

- “Many Name Tea Bags Contain a Copious Amount of Deadly Pesticides.”

- “Dangerously High Pesticides in Celestial Seasonings Teas.”

Yet, the media coverage of pesticides in tea has also highlighted fair causes for concern.

In 2012, Greenpeace purchased 18 teas from random Chinese tea vendors, with seven of the 18 vendors being from among China’s top ten tea sellers. The examiner sent the tea to an independent lab to test pesticide levels. Test results showed that 12 out of the 18 teas (67%) contained toxic pesticides banned in tea production. Such pesticides included endosulfan, which the Stockholm Convention globally banned.

“China is the world’s biggest producer of tea, and it is also the world’s biggest user of pesticides.” – Monica Tan, Greenpeace East Asia.

In 2014, CBC News conducted an independent study of tea brands examining the pesticide levels in everyday tea products sold in Canada. Half of the teas tested contained pesticide residues that exceed Canadian standards. Of the ten brands tested, only Red Rose proved free of pesticide residues.

In 2014, Greenpeace India tested 49 packaged teas from 8 of India’s top 11 tea companies. Products included tea from brands such as Unilever, Tata Global Beverages, and Twinings.

The results of Greenpeace India’s analysis found Highly Hazardous (Class 1B) and Moderately Hazardous (Class II) pesticides in the tea leaves. DDT was present in 67% of the tea samples, even though it’s not registered for use in India’s agriculture. Many of these same tea samples also tested positive for Monocrotophos, a highly hazardous organophosphorus pesticide.

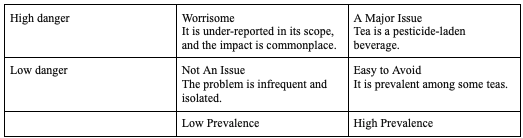

The Four Positions Consumers Can Take on Tea Safety

Tea drinkers can hold one of four positions on the issue of pesticides in tea. These positions can be classified based on danger (risk to the consumer) and prevalence. Prevalence reflects the degree to which teas with pesticide residue are present in the market.

Low prevalence assumes most tea on the market is safe to drink. In such a scenario, consumers can avoid pesticide residue by buying from those who don’t use pesticides in tea. This assumes that enough brands in the tea market are providing pesticide-free tea (e.g., Certified Organic tea).

High prevalence means consumers can’t exert their choice to buy from tea brands that don’t use pesticides in tea. This assumes that there are not enough brands in the tea market meeting this demand; even the specialty tea segment can’t support customer preferences.

Not An Issue: The Problem Is Infrequent And Isolated

Tea drinkers who take the position that pesticides in tea is not an issue believe the problem is occasional and scattered. People who hold this position believe that tea is as safe as other imported products. Such individuals are likely to believe that the headlines about pesticides in tea are scare tactics.

Tea drinkers who believe that unsafe tea is infrequent and isolated instances are likely to point to the following facts:

- 420 food product recalls occurred in 2017; these recalls included voluntary withdrawals and safety alerts issued by the FDA. Only one of the 420 products (0.2%) contained Camellia sinensis, and it was a herbal infusion containing deer antler powder.

- Since 2013, there have been around ten precautionary recalls for salmonella risk. All recalls were for herbal teas because of added ingredients, such as ginger.

Easy To Avoid Issue: The Problem Is Prevalent In Some Teas

Tea drinkers in this segment believe that pesticides in tea are a legitimate issue, but one that can be avoided by adjusting purchasing decisions.

Tea drinkers who hold this position think there are too many sources corroborating the issue to ignore. They consider the media headlines and some scientific reports to be sufficient evidence of a serious issue. Yet tea drinkers who take this stance usually believe the problem of pesticide residue is most prevalent among cheap teas.

Some in this segment may be particularly wary of teas from certain countries, such as China and India, two of the largest global tea producers. They believe teas from these countries are more likely to contain pesticide residues, lead from car emissions, chemicals from coal burning, and air pollutants.

Tea drinkers in this category believe the problem is prevalent in some teas, and that the issue of pesticides in tea can be avoided by adjusting purchasing decisions. They are also more likely to educate themselves on tea quality, origin, and sustainability.

Worrisome: Pesticides In Tea Is A Dangerous, Under-Reported Issue

Tea drinkers in this category take the stance that pesticides in tea are a dangerous and underreported issue. Such tea drinkers worry that major brands downplay the extent and degree of legal controls being bypassed.

Those in this segment of tea drinkers are more likely to think that many teas on the market do not meet import requirements. Tea drinkers who believe the issue of pesticide residue in tea is worrisome are likely to cite several studies that list many mainstream brands as non-compliant.

A Major Issue: Tea Is Basically A Pesticide-Laden Beverage

Tea drinkers in this segment believe pesticides in tea are a major issue; they think it’s serious, widespread, and highly risky for tea consumers and workers.

These tea drinkers believe that pesticides in tea is a threat to the food chain, and view it as a type of widespread corner-cutting in quality control. Such tea drinkers view pesticides in tea within the escalating response to biodegradation, climate change, and the intense economic pressure of global overcapacity and falling prices.

Tea drinkers who fall within this segment are likely to voice strong concerns over other food and environmental issues. This segment of tea drinkers is also most likely to question whether sustainable tea and food production can be implemented at such a scale that it mitigates the problem of pesticides.

Tea drinkers in this segment believe tea is a pesticide-laden beverage, and are likely to cite reports by leading think tanks, international policy, industry, and research groups.

The Risks of Pesticides In Tea

Consumers are keenly aware that contaminants pose potential health risks (El-Aty, 2014), and the possible health effects of pesticide exposure are of great concern for tea drinkers (Lu, 2020).

Tea is a valuable cash crop in China, the most significant producer of tea globally. High rates of chemical fertilizer and pesticides increase tea yields in China (Xie, 2018). However, increasing the use of fertilizers and pesticides does not always proportionally increase tea yield.

The application of pesticides to tea also comes with a significant increase in human risk. For example, a heavy reliance on pesticides exposes female garden workers to many chemicals, which research links to harmful birth outcomes for these women (Kumar, 2020).

Tea drinkers consume pesticide residue in tea. During the infusion process, a significant percentage of the pesticide residues are transferred to the infusions. This is particularly true of pesticides with high water solubility. The percentage of pesticides transferred from tea to the tea infusions ranges from 6.74% (heptachlor) to 86.6% (endrin) (Witczak, 2017).

The health risk posed by pesticide residues for tea drinkers is negligible if pesticide residues satisfy strict regulatory standards and the pesticides are approved (Lu, 2020). However, the following five legacy pesticides, which are not approved for use in tea cultivation, are still identified in some teas.

Harmful legacy pesticides residue found in tea:

- DDT,

- methomyl,

- carbofuran,

- dicofol and

- endosulfan

Measuring And Permitting Pesticides In Tea: MRLs

Maximum residue limits (MRLs) reflect the maximum concentration of pesticide residue likely to occur in a food product. MRLs are expressed as mg of residue per kg of food.

MRLs for pesticides in teas exist for quality control and consumer health protection. Regulatory bodies set MRLs in many countries and regions, including Europe. MRLs assume that pesticides used on foodstuffs follow good agricultural practices (GAP) and product label recommendations.

MRLs are not fixed; they differ between countries. MRLs are trade rules set by regulators and import authorities in individual nations. The EU is known for its firm stance on consumer safety; the MRL threshold for pesticides is often lower than other countries.

MRLs reflect a nations’ “tolerance level” for the level of risk the government is prepared to expose their consumers. When governments and regulative bodies define a country’s MRL levels, they often include a large safety margin.

The various MRLs governments select also impact trade, and China has openly labeled MRLs as an arbitrarily imposed non-tariff barrier to trade. For example, Japan has strict and enforced regulations on the use of pesticides in tea. There have been instances where teas have been locked out of Japanese markets by an MRL of 0.2 mg/kg of pesticides (e.g., Dicofol), even where medical evidence suggests human tolerance may be within a 2.0 range.

As MRL thresholds are not harmonized, nations that produce tea for export (e.g., China, India, Kenya) cannot reference a single accepted standard for pesticides in tea. This imposes a burden on producing nations, making it difficult to conform to global markets.

Sensationalist headlines (e.g., Greenpeace studies) can skew information while seeming credible. Many tea samples can be collected, and the milligrams of detected pesticide residue per kilo (mg/kg) can be determined. These findings can then be compared to the most stringent MRL threshold.

Here’s an example of how such studies can skew and misrepresent finings. Acephate is a commonly used insecticide in tea production.

- China has an MRL of 0.1 mg of Acephate per kilogram of tea

- The EU has an MRL of 0.05 mg of Acephate per kilogram of tea

- Japan has an MRL of 10 mg of Acephate per kilogram of tea

A Chinese tea sample may have 0.09 mg of Acephate per kilogram of tea, compliant with China’s MRL. But if this sample used the EU MRL (0.05 mg/kg) as the baseline for the study, the sample would not be compliant. The body conducting this study could entice people to read their article with a sensationalist headline. Such a headline could be “Chinese Tea exceeded legal pesticide levels by 180%! (according to new research)”.

An example similar to this occurred in the infamous Greenpeace report on Chinese tea. Green tea from one of China’s biggest tea brands was tested. Tests revealed that the pesticide residue in the tea leaves was 0.13 mg/kg for one specific substance. The EU’s MRL was 0.01 for that substance. By the EU’s definition, the tea was not safe. Yet the US’s MRL for the same substance was 50 mg/kg; the tested tea was safe in the US market.

MRL figures measure the residue in the trade form of the tea: the dried leaf. This measurement of pesticides in the dried leaf doesn’t accurately translate into the tea the customer drinks. For example, the pesticide concentration in matcha (powdered green tea leaves) and a simple tea infusion. Several pesticides are insoluble and do not leach into the water. In such cases of insoluble pesticides, the consumer drinking the infusion would not be at risk, while the consumer drinking the micro-ground tea may be.

The Real Risks of Tea As A Decoction

In some countries, including India and Egypt, tea is drunk as a decoction; tea and water are boiled together. (El-Aty, 2014)

This method of preparing tea may pose greater risks to tea drinkers, as boiling water and tea together in a decoction brings all soluble and insoluble components together. Therefore, a cup of tea may contain various kinds of contaminants (El-Aty, 2014).

Such contaminants can include:

- pesticides,

- environmental pollutants,

- mycotoxins,

- microorganisms,

- toxic heavy metals,

- radioactive isotopes (radionuclides), and

- plant growth regulators

Research suggests that the traditional practice of over-boiling tea leaves should be discouraged; there may be a chance of more contaminants from the tea to the brew (El-Aty, 2014).

Steps You Can Take To Mitigate Risk

There are two ways to reduce your exposure to pesticides and insecticides in tea: through your purchasing decision and preparation.

Buy From Brands That Wash Tea Before Harvest

Washing fresh tea leaves before picking decreases pesticide residues in tea. Pesticide residues can be reduced by 16-89% when the new tea shoots are sprayed with water seven days before harvest (Gao, 2020). Some tea brands (e.g., Millena Tea) wash tea leaves after plucking, but washing tea leaves before or after plucking is not common in the tea industry.

Rinsing Your Tea

Rinsing dried tea leaves before brewing reduces the levels of pesticide residues in the tea infusion (Gao, 2018). To rinse your tea, quickly infuse it (e.g., steep your tea for 30 seconds) and throw away this first infusion. Then reinfuse your tea for the appropriate duration (e.g., 3 – 5 minutes), and enjoy it.

The Under-Discussed Drawbacks Of Organic Tea

Consumers attach much significance to the term “organic”; often, consumers view organic tea as a solution to pesticides in tea.

Consumers purchase organic tea because they assume no pesticides are used in such products, but this is an incorrect assumption. Organic tea uses pesticides derived from natural sources, not synthetic ones. For example, the US Organic Standards approves approximately twenty chemical insecticides, fungicides, and herbicides.

Many large organic farms use these approved pesticides liberally. The top two organic fungicides (copper and sulfur) were used at a rate of 4 and 34 pounds per acre. By contrast, synthetic fungicides only require an application rate of 1.6 lbs per acre, less than half the organic alternatives.

While such pesticides are natural, they are not always safe. For example, for decades producers have widely used rotenone as a broad-spectrum insecticide. Rotenone occurs naturally in the seeds and stems of several plants and was assumed to be safe. Yet research shows it increased the risks of Parkinson’s Disease by killing mitochondria in cells (Radad, 2019).

When teas claim to be organic, they are claiming a certification, not a description of production. Several teas on the market may be grown without synthetic pesticides and herbicides but cannot be called organic because they have not paid for and passed the certification requirements.

It is often expensive and inaccessible for farmers to certify tea as organic. For example, tea growers must pay hefty fees for inspection, consultation, and tests in tea producing countries (e.g., China). Such farmers must also make capital investments in record-keeping systems as part of the certification requirements.

Organic teas also pose a greater risk to tea drinkers in specific areas. For example, organics can have higher levels of pathogens spread by fecal contamination from natural manure.

In China, there are also many reports of corruption. Such instances of corruption include cases of mass commercial farms exploiting their size to be certified organic and gain a marketing advantage. In such cases of corruption, a tea may be certified organic without being so.

How The Issue Of Pesticides In Tea Has Evolved

Food safety and import controls have tightened substantially. Exporters can no longer dump pesticide-laden tea on regulated markets (e.g., EU, Japan, Canada, US). Actions taken to de-incentivize exporters from dumping non-compliant tea on importing markets include administrative sanctions, notifications, market withdrawal, and bans.

As proof of these tight regulations, only one of 400 FDA food recalls and alerts was for tea. And a 2013 EU report shows that tea, coffee, and herbal teas combined had less than half the non-compliance rate of legume vegetables, amounting to 5.1% of the total.

Beyond Impressions: The Emerging Picture

Pesticides are not inherently bad. Bad and good are outcomes of the broader biodynamic management process.

Pesticide-free food production isn’t feasible. Producing tea at scale and at accessible price points necessitates pesticides. Tea grows in subtropical climates, which are breeding grounds for around three hundred varieties of voracious pests. Without pesticides, 10-40% of the tea crop would be lost from a harvest.

Many of the best teas are produced in tea gardens using bio-management methods, which are not organic but are as pesticide-free as possible. Some research suggests that replacing 20-50% of conventional (synthetic) fertilizer with organic, and reducing pesticide application by 30-50% produces beneficial results (Xie, 2018).

Often, tea grown without pesticides may still have pesticide residue; the application of pesticides to tea crops in one location can affect tea grown in other nearby locations.

For example, pesticides applied to tea plants in location “A” can affect the surrounding environment. The pesticides can transfer by leaching and land run off into a shared water source. Then, tea farmers in location B apply pesticides to their tea crops using water from the shared source.

Synthetic pesticides in organic tea often come from neighboring farms, water runoff, pollution, and poor soil management. Consumer Reports tested a thousand pounds of organically labeled food for 300 synthetic pesticides, and they found traces of them in 25% of the organically-labeled foods.

However, when tea farmers replace synthetic fertilizer with organic fertilizer, it can significantly reduce chemicals in runoff water. For example, it reduces the runoff of ammonium nitrogen (NH4-N), nitrate-nitrogen (NO3-N), total phosphorus (TP), and total potassium (TK)(Xie, 2018).

The application of pesticides influences tea terroir, the sum of all environmental conditions affecting tea production. Tea terroir includes location, soil, climate patterns, biodiversity, elevation, culture, and bio-management methods.

Chinese scholars are exploring ways that pesticide use in tea can be reduced using biodiversity. Predation, one animal preying on others, is an aspect of natural pest control. Protecting predators in insects could help suppress pests, contributing to a reduced need for pesticides in tea production (Imboma, 2020).

There are relatively few regions where all factors of terroir occur perfectly, naturally. In regions that are less vulnerable to infestation, farmers are less incentivized to use pesticides. The best terroirs for tea are mountainous regions noted for their pedigree teas:

- Uji,

- Darjeeling,

- Wuyi,

- Alishan,

- Xishuangbanna, and

- Nuwara Eliya

Traceability is a vital countermeasure to using pesticides in tea. Consumers and brands should be able to trace tea products back to the producing farms and factories at any step in the supply chain.

Fortunately, major consumer brands are tightening links to producers, and the last several years have seen a growing emphasis on the responsible cultivation of tea. Such leading brands provide incentives and support to producers committing to sustainable development.

Tea consumers should also know their brands. The solution to real and perceived risk is knowledge and transparency. Consumers should treat tea as a high-involvement purchase; learn about a tea company’s suppliers, the growers, terroir, and pedigree.

Do you think organic tea is better than conventionally grown tea? Leave a comment below sharing your perspective.

References

El-Aty, A. A., Choi, J., Rahman, M. M., Kim, S., Tosun, A., & Shim, J. (2014). Residues and contaminants in tea and tea infusions: A review. Food Additives & Contaminants: Part A, 31(11), 1794-1804. doi:10.1080/19440049.2014.958575

Gao, W., Yan, M., Xiao, Y., Lv, Y., Peng, C., Wan, X., & Hou, R. (2018). Rinsing Tea before Brewing Decreases Pesticide Residues in Tea Infusion. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 67(19), 5384-5393. doi:10.1021/acs.jafc.8b04908

Gao, W., Guo, J., Xie, L., Peng, C., He, L., Wan, X., & Hou, R. (2020). Washing fresh tea leaves before picking decreases pesticide residues in tea. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 100(13), 4921-4929. doi:10.1002/jsfa.10553

Imboma, T. S., Gao, D., You, M., You, S., & Lövei, G. L. (2020). Predation Pressure in Tea (Camellia sinensis) Plantations in Southeastern China Measured by the Sentinel Prey Method. Insects, 11(4), 212. doi:10.3390/insects11040212

Kumar, S. N., Vaibhav, K., Bastia, B., Singh, V., Ahluwalia, M., Agrawal, U., . . . Jain, A. K. (2020). Occupational exposure to pesticides in female tea garden workers and adverse birth outcomes. Journal of Biochemical and Molecular Toxicology, 35(3). doi:10.1002/jbt.22677

Lu, E., Huang, S., Yu, T., Chiang, S., & Wu, K. (2020). Systematic probabilistic risk assessment of pesticide residues in tea leaves. Chemosphere, 247, 125692. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.125692

Ly, T., Ho, T., Behra, P., & Nhu-Trang, T. (2020). Determination of 400 pesticide residues in green tea leaves by UPLC-MS/MS and GC-MS/MS combined with QuEChERS extraction and mixed-mode SPE clean-up method. Food Chemistry, 326, 126928. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.126928

Radad, K., Al-Shraim, M., Al-Emam, A., Wang, F., Kranner, B., Rausch, W., & Moldzio, R. (2019). Rotenone: From modelling to implication in Parkinson’s disease. Folia Neuropathologica, 57(4), 317-326. doi:10.5114/fn.2019.89857

Witczak, A., Abdel-Gawad, H., Zalesak, M., & Pohoryło, A. (2017). Tracking residual organochlorine pesticides (OCPs) in green, herbal, and black tea leaves and infusions of commercially available tea products marketed in Poland. Food Additives & Contaminants: Part A, 35(3), 479-486. doi:10.1080/19440049.2017.1411614

Xie, S., Feng, H., Yang, F., Zhao, Z., Hu, X., Wei, C., . . . Geng, Y. (2018). Does dual reduction in chemical fertilizer and pesticides improve nutrient loss and tea yield and quality? A pilot study in a green tea garden in Shaoxing, Zhejiang Province, China. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 26(3), 2464-2476. doi:10.1007/s11356-018-3732-1

Zhu, B., Xu, X., Luo, J., Jin, S., Chen, W., Liu, Z., & Tian, C. (2019). Simultaneous determination of 131 pesticides in tea by on-line GPC-GC–MS/MS using graphitized multi-walled carbon nanotubes as dispersive solid phase extraction sorbent. Food Chemistry, 276, 202-208. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.09.152

Note that this is a general response to the issues raised.

Regarding the OOS (out of specification) examples reported in the “Pesticides in Tea: Getting a Clear Picture not a Vague Impression” article, this eloquently reports a big-picture example of identifying what appears to be major concerns in the global quality supply chain This information will hopefully bring more awareness to these product quality issues of concern; after all, we all want to consume safe and healthy food products.

From my experience working with manufacturing botanical ingredient health products, an effective supplier qualification /certification program, including active monitoring, is required along with an aggressive quality control program that includes testing for pesticides, heavy metals, and other constituents of concern, at least on the incoming raw materials and finished products too. This is done for each lot/batch, no skipping. When a finished product is tested and is OOS for pesticides or heavy metals or some other specification, the quality management system has failed and swift corrective actions are required.

OOS can be a symptom of one or more quality management related problems that may require one or many actions, including training, new and/or revised SOPs, new personnel, expert consultants, quality systems auditing and improvements, product testing method review and validation, and supplier re-qualification, for example. Also, an annual independent quality management audit with a scoring system for specific action item follow-up is beneficial as part of a quality management system.

Failure of a quality management system is unacceptable with today’s incredible technology. Yes, suppliers occasionally ship to their manufacturing customers OOS ingredients, as the article exemplifies, but the quality control system of the finished product company needs to identify OOS ingredients and prevent using them in their products. This is the black and white perspective. However, the real-world perspective sometimes complicates things, which is another story, and can lead to causing OOS situations.

Ideally, when a third party is testing finished products the product company should be contacted prior to testing for a few reasons, including: knowing about the established product specifications and testing methods; to immediately alert a product company if third party testing result indicates an OOS situation so the product company can conduct a prompt OOS investigation; and to have the opportunity to evaluate the third party testing methods/results, which could have issues and often do in my experience.

Product companies with a good quality control program benefit tremendously and are rewarded with a high level of consumer safety and satisfaction.

Daniel Gastelu, MS, MFS, President/Scientist

Health Product Business Success LLC

contact@hpbsllc.com

I appreciate the additional perspective. Question: if you drink tea, which tea(s) do you drink. I ask this, knowing that, speaking for myself, it is one thing to deliberately ingest anything when the possible effects are known, and quite another when one had not made the proper inquiries. “Tea.” Sounds so simple, relatively speaking. Thank you.

Daniel – that’s an interesting perspective. However if tea producers tested each lot or batch for heavy metals and pesticides they would be out of business very quickly!

The current approach is to establish robust preventive management systems to ensure that (legitimate) crop chemicals are used properly/sparingly, only when absolutely necessary, and the manufacturers’ instructions are followed to the letter. Non-chemical systems are helpful too of course.

A QA (rather than QC) approach can then be taken if CC usage is properly under control.

Great content, informative and well written. Thanks

The big thing is that most agricultural situations are likely dynamic. Changing rainfall, spilled chemicals, workers who don’t follow procedures for whatever reason and companies who have to make a profit no matter what. So if things change in the tea growing workstream, unknown to the people who have decided that things “should” be going well customers will get OOS tea leaves. So tea growers are taking a chance on customers health sort of without warning them that the tea could hurt them under some situations. Hard to tell, harder to prove. The fact that a scientist will vouch for the process is nice, but there appear to be lots of opportunities for errors. Not to mention that the quest for maximun profits makes little problems easy to overlook.

I have been gifted with three containers of supposedly premium teas which originated in China. Before I use or discard these products, where can I get these products tested in Canada?

EMSL will do a fine job testing these teas for you Julie. http://foodtestinglab.com/

If the tins are sealed, safety can be easily verified by reviewing labeling as all China tea exports must comply with stringent testing requirements. You can also visit the brand’s website for verification via third party inspectors.

Dan

Since the country origin of the purchase of these gifts cannot be verified but it is likely China, no information is printed in English but the label bears a number on each of the tea products. Would that information be helpful in tracking the safety of the product?

This is a very interesting read. Loved the points you make. Am sharing your blog for further circulation.

Which part of processing of the raw leaf can breakdown the commonly used pesticide residues in tea. For example, does the process of making CTC render a safer product in terms of pesticide residues against that less processed orthodox or green teas? Any findings?